Over many years as an affordable aviation journalist I have learned two things. First, stick to airplanes. That’s what moves the needle for most pilots; nearly always such articles are the best-read on this website. Second, pilots love more powerful engines, especially when they display new technologies.

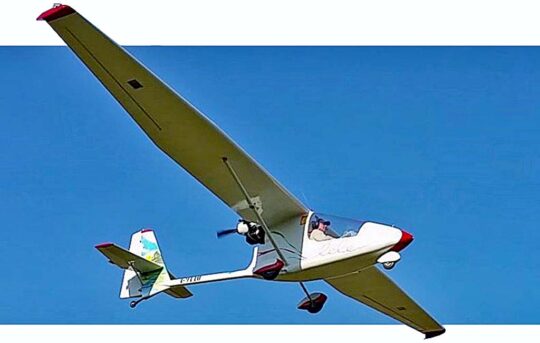

Speedy LSA maker, JMB Aircraft has tapped into this rich vein of interest. For some years, they have worked to make their elegant and shapely VL3 go faster than before (earlier evaluation article). A year ago at Sun ‘n Fun, the Belgium-headquartered company showed Americans their 141-horsepower Rotax 915iS model. The machine looked quick merely sitting in their display.

That wasn’t enough. Even though JMB can max out at 230 mph now, leaders and engineers at JMB thought, “Why not try a turboprop?”

JMB Turbine

Not even a month ago, this leading builder of LSA speedsters took their turbine-powered VL3 into the air for the first time, in France on Monday April 4th, 2022.

Over many years as an affordable aviation journalist I have learned two things. First, stick to airplanes. That’s what moves the needle for most pilots; nearly always such articles are the best-read on this website. Second, pilots love more powerful engines, especially when they display new technologies.

Speedy LSA maker, JMB Aircraft has tapped into this rich vein of interest. For some years, they have worked to make their elegant and shapely VL3 go faster than before (earlier evaluation article). A year ago at Sun ‘n Fun, the Belgium-headquartered company showed Americans their 141-horsepower Rotax 915iS model. The machine looked quick merely sitting in their display.

That wasn’t enough. Even though JMB can max out at 230 mph now, leaders and engineers at JMB thought, “Why not try a turboprop?”

JMB Turbine

Not even a month ago, this leading builder of LSA speedsters took their turbine-powered VL3 into the air for the first time, in France on Monday April 4th, 2022.Europe’s Passionate Need for Speed — JMB Enlists Turbine Power to Go Faster Yet

Over many years as an affordable aviation journalist I have learned two things. First, stick to airplanes. That’s what moves the needle for most pilots; nearly always such articles are the best-read on this website. Second, pilots love more powerful engines, especially when they display new technologies.

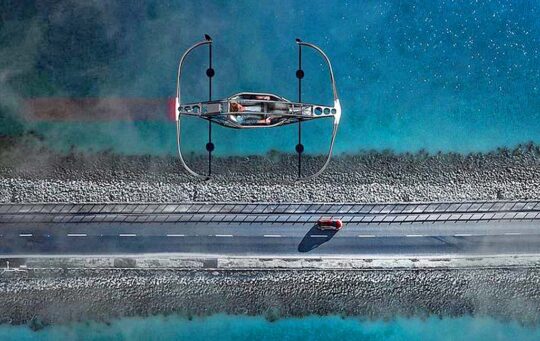

SOARING HIGH — JMB Aircraft’s display at AERO Friedrichshafen 2022. photo by John Rathmell

Speedy LSA maker, JMB Aircraft has tapped into this rich vein of interest. For some years, they have worked to make their elegant and shapely VL3 go faster than before (earlier evaluation article). A year ago at Sun ‘n Fun, the Belgium-headquartered company showed Americans their 141-horsepower Rotax 915iS model. The machine looked quick merely sitting in their display.

That wasn’t enough. Even though JMB can max out at 230 mph now, leaders and engineers at JMB thought, “Why not try a turboprop?”

JMB Turbine

Not even a month ago, this leading builder of LSA speedsters took their turbine-powered VL3 into the air for the first time, in France on Monday April 4th, 2022. Later that month, the company debuted the development to crowds at Aero Friedrichshafen 2022.

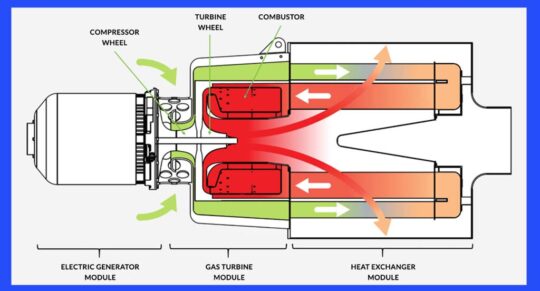

JMB has installed a French-designed engine from TurboTech (the same powerplant used on Bristell’s new entry). According to the French engine developer, the TP-R90 outputs 130 horsepower, burns five gallons per hour in “eco-cruise,” and weighs 176 pounds for the “full package” (though final installed weight may vary by airframe). TurboTech clarified, “A regenerative turbine is a turbine engine equipped with a heat exchanger (nearby diagram) capable of recovering the heat normally wasted in exhaust gases and reinjecting it into the combustion chamber, leading to a dramatic fuel burn reduction.”

Piloting the first flight of their VL3 Turbine Jean-Baptiste Guisset, CEO of JMB, flew at France’s Valenciennes airfield under the supervision of the designers of the French turbine.

TURBINE POWER — TurboTech’s heat-exchanger turbine engine is being used on three LSA designs.

“A VL3 turbine is easier to fly than a traditional piston aircraft,” added JMB, “thanks to the electronic management of the FADEC and its unique lever.” Not only do they report modest fuel burn rates, thanks to the heat exchanger, but kerosene price is also a good advantage compared to the fuel normally used,” observed Jean-Marie Guisset.

In six months of development testing, JMB reported more than 50 hours of ground testing, including 30 hours of full power testing. “In only 8 days, we flew more than 20 hours and simulated all possible failures without any technical issues.”

“We already have two aircraft equipped with the turbine and have elaborated an advanced flight program for the coming months in order to test all the flight domains of the turbine,” concluded JMB.

Longer Life / Cheaper Fuel

Proponents of TurboTech’s method say it is superior due to its longer time before overhaul (TBO).

WIDER USES — TurboTech also envisions their turbine as a generator for hybrid-electric propulsion.

Other commenters cite as a primary benefit: reliability. Turbine engines run at high revolutions but are built with such precision that they can last longer than a reciprocating engine. Due to their design, reciprocating engines produce vibration. As vibration can harm an airframe over a long life, a smoother turbine may add to an airplane’s duty cycle though this is hardly a major concern for recreational planes that log 50-100 hours per year. Unless you log far more hours than average, you may never need to overhaul your turbine JMB.

FAA’s Mosaic & Turbines?

The short answer about turbines being permitted: We don’t know today but we might find out at Oshkosh 2022 when I expect FAA will release the draft regulation as a Notice of Proposed Rule Making (NPRM).

LONG & LEAN — JMB Aircraft’s installation of the TP-R90 turbine into their VL3 model. photo by John Rathmell

What we do know is that FAA deliberately eliminated turbine engines when they released the Sport Pilot / Light-Sport Aircraft regulation in 2004. In those days, a turbine engine was viewed as too complex for sport enthusiasts so FAA specified “reciprocating” engines only.

As a sign of the times way back then, electric propulsion wasn’t anything of particular interest. A few scattered experimenters had not proven battery-powered aircraft were anything more than a novelty. Requiring internal combustion engines completely ruled out electric motors… all in the interest of keeping turbines out.

Well, FAA also failed to include helicopters but Mosaic might include them. So, might FAA allow turbine, too? Possibly yes, if they are paying attention to what is going in Europe; at least three companies have fitted turbine engines to current-day LSA designs. With the advantages spelled out above, do you think rule writers can or should include turbine? If you agree, get ready to tell FAA by your comments later this year.

Will a Market Arise?

Cost is the main impediment to wider acceptance. At almost $100,000 for the engine alone (according to an estimate from Bristell rep’, John Rathmell at Aero 2022), the TurboTech power plant is almost three times as costly as a Rotax 915iS yet it outputs 10 or more horsepower less than the turbocharged, intercooled Rotax. No matter its extra benefits, that cost will prove prohibitive for most buyers. Yet if you think it won’t sell, then tell me how Cirrus keeps selling hundreds of their nearly-million-dollar SR-series aircraft year after year.

I understand most buyers will probably not elect turbine power no matter its advantages because the cost is breathtakingly higher. Nonetheless, well-heeled pilots with a need for speed and a love of the latest thing may go for it. The rest of us will fly what we can afford and the great news is — something is available for almost every budget.

Over many years as an affordable aviation journalist I have learned two things. First, stick to airplanes. That’s what moves the needle for most pilots; nearly always such articles are the best-read on this website. Second, pilots love more powerful engines, especially when they display new technologies.

Speedy LSA maker, JMB Aircraft has tapped into this rich vein of interest. For some years, they have worked to make their elegant and shapely VL3 go faster than before (earlier evaluation article). A year ago at Sun ‘n Fun, the Belgium-headquartered company showed Americans their 141-horsepower Rotax 915iS model. The machine looked quick merely sitting in their display.

That wasn’t enough. Even though JMB can max out at 230 mph now, leaders and engineers at JMB thought, “Why not try a turboprop?”

JMB Turbine

Not even a month ago, this leading builder of LSA speedsters took their turbine-powered VL3 into the air for the first time, in France on Monday April 4th, 2022.

Over many years as an affordable aviation journalist I have learned two things. First, stick to airplanes. That’s what moves the needle for most pilots; nearly always such articles are the best-read on this website. Second, pilots love more powerful engines, especially when they display new technologies.

Speedy LSA maker, JMB Aircraft has tapped into this rich vein of interest. For some years, they have worked to make their elegant and shapely VL3 go faster than before (earlier evaluation article). A year ago at Sun ‘n Fun, the Belgium-headquartered company showed Americans their 141-horsepower Rotax 915iS model. The machine looked quick merely sitting in their display.

That wasn’t enough. Even though JMB can max out at 230 mph now, leaders and engineers at JMB thought, “Why not try a turboprop?”

JMB Turbine

Not even a month ago, this leading builder of LSA speedsters took their turbine-powered VL3 into the air for the first time, in France on Monday April 4th, 2022.

OK, I know turbines are not allowed on present-day LSA. Could that be changing as Mosaic slowly works its way through the FAA? We won’t know until FAA releases their NPRM at this year’s Oshkosh (I predict). However, some language provided by the agency to guide ASTM standards writers has suggested that the ban on turbines might not last.

OK, I know turbines are not allowed on present-day LSA. Could that be changing as Mosaic slowly works its way through the FAA? We won’t know until FAA releases their NPRM at this year’s Oshkosh (I predict). However, some language provided by the agency to guide ASTM standards writers has suggested that the ban on turbines might not last. A irony to this possibility is that turbines were the specific reason why electric wasn’t permitted. Uh… what?! Yep, in the effort to prevent turbines, FAA rule writers specified reciprocating engines only. That kept out turbines, alright, but it also scratched electric propulsion. Back in the early 2000s, government authorities weren’t pushing electric vehicles so rule writers didn’t feel the political pressure they do now.

A irony to this possibility is that turbines were the specific reason why electric wasn’t permitted. Uh… what?! Yep, in the effort to prevent turbines, FAA rule writers specified reciprocating engines only. That kept out turbines, alright, but it also scratched electric propulsion. Back in the early 2000s, government authorities weren’t pushing electric vehicles so rule writers didn’t feel the political pressure they do now. “

“ “Bristell B8 is an all-metal, high-wing [design] without struts and with a steerable nose wheel,” said the company. Although it looks quite different from the low wing, B8’s cockpit is equally spacious at 49.2 inches wide. Pilots and their cabin mates will no doubt find entry much easier than first climbing up on the wing. Generally, pilots identify as high or low wing enthusiasts and now BRM can offer them what they want.

“Bristell B8 is an all-metal, high-wing [design] without struts and with a steerable nose wheel,” said the company. Although it looks quite different from the low wing, B8’s cockpit is equally spacious at 49.2 inches wide. Pilots and their cabin mates will no doubt find entry much easier than first climbing up on the wing. Generally, pilots identify as high or low wing enthusiasts and now BRM can offer them what they want. H55 is a leading enabler of electric aviation offering modular, lightweight, and certified electric propulsion and battery management solutions to the aviation industry as to make air transport, quiet, clean and affordable. “H55 supports its customers in integrating and customizing its technology solutions for a wide range of applications suitable for both existing airplane designs and future concepts such as VTOLs and e-commuter aircraft,” said the Swiss company.

H55 is a leading enabler of electric aviation offering modular, lightweight, and certified electric propulsion and battery management solutions to the aviation industry as to make air transport, quiet, clean and affordable. “H55 supports its customers in integrating and customizing its technology solutions for a wide range of applications suitable for both existing airplane designs and future concepts such as VTOLs and e-commuter aircraft,” said the Swiss company. The result? An electric LSA-style aircraft with a 419-pound payload, an 1,874-pound MTOW, a climb rate of 800 feet per minute, and electric energy cost for a one-hour flight of $7.00. Charging time for normal operations is reportedly just one hour. BRM Aero expects to achieve CS23 certification by mid-2022. It should be available for flight schools as soon as mid-2022, the company said.

The result? An electric LSA-style aircraft with a 419-pound payload, an 1,874-pound MTOW, a climb rate of 800 feet per minute, and electric energy cost for a one-hour flight of $7.00. Charging time for normal operations is reportedly just one hour. BRM Aero expects to achieve CS23 certification by mid-2022. It should be available for flight schools as soon as mid-2022, the company said. I elected not to go to what would have been my 27th visit to Aero because just two months ago, when I needed to make air reservations, Covid panic still gripped Europe. Officially in mid-February, the show could not even be held. It looked too questionable for me to go forward with costly tickets amid global uncertainty; I was unwilling to chance being quarantined for two weeks at my own expense. Challenges of obtaining the right Covid documents also proved difficult. Fortunately for the beleaguered Aero organizers, things opened up but now I’m missing one of my favorite airshows of the year. So, a big thanks to John Rathmell of

I elected not to go to what would have been my 27th visit to Aero because just two months ago, when I needed to make air reservations, Covid panic still gripped Europe. Officially in mid-February, the show could not even be held. It looked too questionable for me to go forward with costly tickets amid global uncertainty; I was unwilling to chance being quarantined for two weeks at my own expense. Challenges of obtaining the right Covid documents also proved difficult. Fortunately for the beleaguered Aero organizers, things opened up but now I’m missing one of my favorite airshows of the year. So, a big thanks to John Rathmell of

I captured video from multiple cameras for each aircraft; watch for our video pilot report soon. While the video is in editing, I will give a short review of the Stream. This was a new experience for me.

I captured video from multiple cameras for each aircraft; watch for our video pilot report soon. While the video is in editing, I will give a short review of the Stream. This was a new experience for me. Up front instrumentation is larger and you do fly solo from the front. Yet in the back, I had a seven-inch Garmin touch screen that provided the same info in a smaller package. For example, the gear position shows in both locations… although, like most digital screens, it may take a while to pick out the data you want from all that is displayed.

Up front instrumentation is larger and you do fly solo from the front. Yet in the back, I had a seven-inch Garmin touch screen that provided the same info in a smaller package. For example, the gear position shows in both locations… although, like most digital screens, it may take a while to pick out the data you want from all that is displayed. However, in one way the front proves superior, regarding runway visibility on approach to landing. With no flaps or with one notch deployed, I had no sight picture from the aft seat. However, with full flaps, I could easily keep an eye on the runway. An offset to the aft seat visibility looking forward is that you have an excellent straight down view that the front PIC seat lacks; the pilot up front is seated at the wing midpoint so downward visibility is restricted.

However, in one way the front proves superior, regarding runway visibility on approach to landing. With no flaps or with one notch deployed, I had no sight picture from the aft seat. However, with full flaps, I could easily keep an eye on the runway. An offset to the aft seat visibility looking forward is that you have an excellent straight down view that the front PIC seat lacks; the pilot up front is seated at the wing midpoint so downward visibility is restricted. What you might be more surprised to learn is how gentle its stall characteristics are and how slow it can go on landing.

What you might be more surprised to learn is how gentle its stall characteristics are and how slow it can go on landing. Since I mentioned the aircraft speeds along quite well, I rush to say I was rather amazed that Stream could slow down into the high-30s (knots) when flaps are deployed. From 39 knots indicated to 150 knots in cruise, we start to approach that magic 4:1 stall-to-cruise target that any designer likes to achieve (it’s not an easy mark to hit).

Since I mentioned the aircraft speeds along quite well, I rush to say I was rather amazed that Stream could slow down into the high-30s (knots) when flaps are deployed. From 39 knots indicated to 150 knots in cruise, we start to approach that magic 4:1 stall-to-cruise target that any designer likes to achieve (it’s not an easy mark to hit). Then, through a series of turns, I discovered that Stream will hold its altitude very well without power or trim adjustments of any kind. Of course, using those controls will make handling even better I suspect, but stick pressures remained light and it was simply unnecessary to employ those controls in order to produce turns that maintained altitude and speed. These are wonderful characteristics for Stream to demonstrate.

Then, through a series of turns, I discovered that Stream will hold its altitude very well without power or trim adjustments of any kind. Of course, using those controls will make handling even better I suspect, but stick pressures remained light and it was simply unnecessary to employ those controls in order to produce turns that maintained altitude and speed. These are wonderful characteristics for Stream to demonstrate.

One such example is a fascinating collaboration, in this case between two companies each producing a substantially authentic scale model replica of the famous World War II fighter. One has a market established over several years. The other has a spectacular new entry. How can you imagine the story ends?

One such example is a fascinating collaboration, in this case between two companies each producing a substantially authentic scale model replica of the famous World War II fighter. One has a market established over several years. The other has a spectacular new entry. How can you imagine the story ends? Christian von Kessel of

Christian von Kessel of  As

As  Ron showed active work on the project as they unveiled their new nose cowling at Sun ‘n Fun. If you look at the earlier article you’ll see they’ve made a quality upgrade. This happened when an automobile industry engineer with an interest in airplanes offered to assist Thunderbird. He was able to employ his skills including use of an auto company wind tunnel to refine the shape. As the nearby images show, the work reveals professional quality; the shape is excellent. Will it be all done by AirVenture Oshkosh 2022? No, but it’ll be coming along this year, Ron is sure.

Ron showed active work on the project as they unveiled their new nose cowling at Sun ‘n Fun. If you look at the earlier article you’ll see they’ve made a quality upgrade. This happened when an automobile industry engineer with an interest in airplanes offered to assist Thunderbird. He was able to employ his skills including use of an auto company wind tunnel to refine the shape. As the nearby images show, the work reveals professional quality; the shape is excellent. Will it be all done by AirVenture Oshkosh 2022? No, but it’ll be coming along this year, Ron is sure. “Hummingbird is an innovative project designed and manufactured by Hummingbird Industria Aeronautica and distributed in North America by

“Hummingbird is an innovative project designed and manufactured by Hummingbird Industria Aeronautica and distributed in North America by  They promote reasonable prices: the two-seater around $75,000 and a single seater around $40,000 (but contact the company for current prices; shipping costs are at crazy levels). The two seat tandem model we saw at Sun ‘n Fun had the

They promote reasonable prices: the two-seater around $75,000 and a single seater around $40,000 (but contact the company for current prices; shipping costs are at crazy levels). The two seat tandem model we saw at Sun ‘n Fun had the

On pleasant evenings, crowds can be five deep all along the runway fence. STOL comps provide exciting close-up action. At few other airports can you observe so closely, literally 100 feet away from runway centerline.

On pleasant evenings, crowds can be five deep all along the runway fence. STOL comps provide exciting close-up action. At few other airports can you observe so closely, literally 100 feet away from runway centerline. Unfortunately Steve broke an axle and ended up on his nose in Wednesdays gusty conditions. Damage was reasonably minor — an advantage of landing so slowly perhaps — and he should be back in action soon.

Unfortunately Steve broke an axle and ended up on his nose in Wednesdays gusty conditions. Damage was reasonably minor — an advantage of landing so slowly perhaps — and he should be back in action soon.

Monster STOL solves that problem, Jan believes. His dual aft shocks on each side have 18 inches of stroke. The tires aren’t tundra but they’re large. And standing Super Duty up on specialized landing gear — which also helps entry into this high-off-the-ground airplane — allows Jan to create a very steep angle of attack.

Monster STOL solves that problem, Jan believes. His dual aft shocks on each side have 18 inches of stroke. The tires aren’t tundra but they’re large. And standing Super Duty up on specialized landing gear — which also helps entry into this high-off-the-ground airplane — allows Jan to create a very steep angle of attack.

Little did we know last year that Putin would invade Ukraine and plunge both countries into disarray. The

Little did we know last year that Putin would invade Ukraine and plunge both countries into disarray. The  At Sun ‘n Fun 2022, Gene “Bever” Borne and son Ken of

At Sun ‘n Fun 2022, Gene “Bever” Borne and son Ken of  Upon closer inspection, this Sprint model was powered by Aero 1000, a single-cylinder, four-stroke engine with impressive specs. Air-Tech said it outputs 39 horsepower — similar to the Rotax 447 — and is extremely economical on fuel.

Upon closer inspection, this Sprint model was powered by Aero 1000, a single-cylinder, four-stroke engine with impressive specs. Air-Tech said it outputs 39 horsepower — similar to the Rotax 447 — and is extremely economical on fuel. Blackhawk’s search for the right engine for their quads lead them to an Swiss engine popular with cart racing enthusiasts. These racers push the engines hard and after years of working to improve the breed, the base engine has become very reliable.

Blackhawk’s search for the right engine for their quads lead them to an Swiss engine popular with cart racing enthusiasts. These racers push the engines hard and after years of working to improve the breed, the base engine has become very reliable. Bever and Ken have fitted the Aero 1000 to their Sprint after building fairly simple hardware to support the engine — see nearby photos of engine and mounts.

Bever and Ken have fitted the Aero 1000 to their Sprint after building fairly simple hardware to support the engine — see nearby photos of engine and mounts.

After we got the LSA Mall set up to receive a flock of airplanes, I was able to get around the sprawling Sun ‘n Fun campus to see what else I planned to cover as the show begins. It starts Tuesday the 5th and runs through Sunday the 10th. I hope you can make it but if not, I’ll be reporting on the aircraft that I think may interest you.

After we got the LSA Mall set up to receive a flock of airplanes, I was able to get around the sprawling Sun ‘n Fun campus to see what else I planned to cover as the show begins. It starts Tuesday the 5th and runs through Sunday the 10th. I hope you can make it but if not, I’ll be reporting on the aircraft that I think may interest you. Now represented in the USA, Bat Hawk travel traveled half way around the globe to get to Sun ‘n Fun. This side-by-side two seater has well established itself in South Africa but will now test interest from Americans. Based on rave reviews from those with experience, the odds look promising.

Now represented in the USA, Bat Hawk travel traveled half way around the globe to get to Sun ‘n Fun. This side-by-side two seater has well established itself in South Africa but will now test interest from Americans. Based on rave reviews from those with experience, the odds look promising. One company has focused for years on creating replicas for famous designs harking back to World War I, a time not long after the Wright Brothers first flew their Flyer on the sand dunes of Kitty Hawk. We’re talking century-old designs, created with slide rules and drafting pape and not much prior art on which to rely.

One company has focused for years on creating replicas for famous designs harking back to World War I, a time not long after the Wright Brothers first flew their Flyer on the sand dunes of Kitty Hawk. We’re talking century-old designs, created with slide rules and drafting pape and not much prior art on which to rely. Replicas are big business in cars, boats, and, of course airplanes. Some like Airdrome cater to one era of history enthusiasts. Others cater to a later war period. Scalewings goes to great effort to make these designs as authentic as possible while building at around 50% of original scale. The task is impressive, enough so that most of us have no real idea of the detail that is goes into something like the model in the photos.

Replicas are big business in cars, boats, and, of course airplanes. Some like Airdrome cater to one era of history enthusiasts. Others cater to a later war period. Scalewings goes to great effort to make these designs as authentic as possible while building at around 50% of original scale. The task is impressive, enough so that most of us have no real idea of the detail that is goes into something like the model in the photos. One of my favorites to come along in the second decade of Light-Sport Aircraft is the

One of my favorites to come along in the second decade of Light-Sport Aircraft is the  I didn’t get to visit with anyone from The Airplane Factory on set-up day to hear if they have any late-breaking news — so I’ll go back, of course — but the sharpest paint job I found anywhere on the grounds was the handsome Sling 4 seen nearby. I have reported on Sling LSA and

I didn’t get to visit with anyone from The Airplane Factory on set-up day to hear if they have any late-breaking news — so I’ll go back, of course — but the sharpest paint job I found anywhere on the grounds was the handsome Sling 4 seen nearby. I have reported on Sling LSA and  If AeroSport sounds busy (and they are!),

If AeroSport sounds busy (and they are!),  To close this preview article so I can go to bed and get ready to do this all again tomorrow, I want to extend a thank you on behalf of myself and

To close this preview article so I can go to bed and get ready to do this all again tomorrow, I want to extend a thank you on behalf of myself and

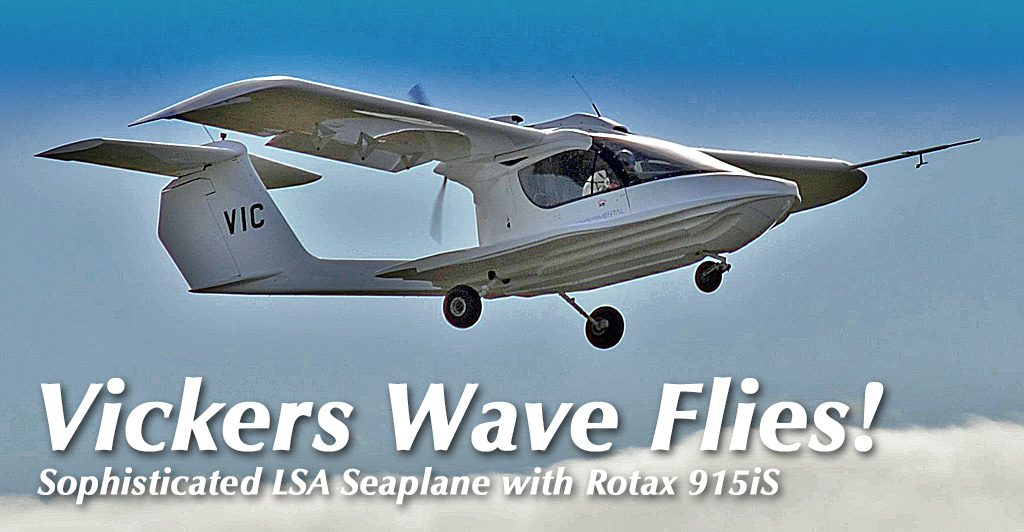

Lead by company namesake, Paul Vickers, Wave has been a work in process for eleven years. All along Paul has been saying he would get it right on the first flight and it looks like he succeeded.

Lead by company namesake, Paul Vickers, Wave has been a work in process for eleven years. All along Paul has been saying he would get it right on the first flight and it looks like he succeeded. “While much of the aircraft is as it will be in final production, the interior and landing gear are purely functional, allowing us to refine and perfect these areas,” explained Paul. As you see in the list below, Wave promises landing gear unlike any other seaplane. “After a series of further test flights, we will be removing the undercarriage and commencing the much-anticipated water testing,” said Paul. “Once we have completed the water testing, we will be fitting our revolutionary undercarriage.”

“While much of the aircraft is as it will be in final production, the interior and landing gear are purely functional, allowing us to refine and perfect these areas,” explained Paul. As you see in the list below, Wave promises landing gear unlike any other seaplane. “After a series of further test flights, we will be removing the undercarriage and commencing the much-anticipated water testing,” said Paul. “Once we have completed the water testing, we will be fitting our revolutionary undercarriage.” “Seeing how stable Wave was in flight is a true testament to taking the time to get things right,” Paul felt. “Always having ‘safety’ as the key driver for every decision has proven to be an incredibly fundamental corner stone for the Wave project; from who we hire to our suppliers and hardware, safety has led our decisions.”

“Seeing how stable Wave was in flight is a true testament to taking the time to get things right,” Paul felt. “Always having ‘safety’ as the key driver for every decision has proven to be an incredibly fundamental corner stone for the Wave project; from who we hire to our suppliers and hardware, safety has led our decisions.” For avionics in the test aircraft as well as in later production aircraft, Vickers had selected Dynon. Other systems will also be offered.

For avionics in the test aircraft as well as in later production aircraft, Vickers had selected Dynon. Other systems will also be offered. “Of all the light airplanes I have flown, Wave is now and by far my favorite,” said Paco. “Paul and his team have done a spectacular job designing and building Wave. It was an honor and privilege to conduct the first flight. I can’t wait to fly Wave again.”

“Of all the light airplanes I have flown, Wave is now and by far my favorite,” said Paco. “Paul and his team have done a spectacular job designing and building Wave. It was an honor and privilege to conduct the first flight. I can’t wait to fly Wave again.” For those curious about weight exemptions for Light-Sport Aircraft — Wave is the fourth such weight exemption granted. Before them came exemptions for 1,680 pounds and 1,800 pounds (the latter for Terrafugia and SkyRunner. At 1,850 pounds, Wave is the new high-water mark but not by much. Under the coming Mosaic rule, these exemptions may no longer be necessary.

For those curious about weight exemptions for Light-Sport Aircraft — Wave is the fourth such weight exemption granted. Before them came exemptions for 1,680 pounds and 1,800 pounds (the latter for Terrafugia and SkyRunner. At 1,850 pounds, Wave is the new high-water mark but not by much. Under the coming Mosaic rule, these exemptions may no longer be necessary.

“It is the best of the several models of LSA that Zlin has ever made,” SportairUSA boss, Bill Canino said of Norden.

“It is the best of the several models of LSA that Zlin has ever made,” SportairUSA boss, Bill Canino said of Norden. About two years ago,

About two years ago,  Bill worked with FAA representatives to gain acceptance during the fall and winter of 2021-22. “We appreciate the attention to safety that the FAA brings to this process,” said Canino, whose company, SportairUSA, has been a pioneer in the field of Light-Sport Aircraft, serving the experimental and recreational aviation community since 1990.

Bill worked with FAA representatives to gain acceptance during the fall and winter of 2021-22. “We appreciate the attention to safety that the FAA brings to this process,” said Canino, whose company, SportairUSA, has been a pioneer in the field of Light-Sport Aircraft, serving the experimental and recreational aviation community since 1990. “The design of Norden incorporates classic short takeoff and landing (STOL) elements together with innovative concepts tested and proved in previous Zlin products,” said Bill. “Pilot feedback, from the Alaskan bush to the deserts of South Africa, played an important role in Zlin’s evolution as a designer and manufacturer of STOL aircraft.”

“The design of Norden incorporates classic short takeoff and landing (STOL) elements together with innovative concepts tested and proved in previous Zlin products,” said Bill. “Pilot feedback, from the Alaskan bush to the deserts of South Africa, played an important role in Zlin’s evolution as a designer and manufacturer of STOL aircraft.” According to Zlin’s founder, Pasquale Russo, “The design target was to offer to the market a new version of our plane with improved STOL performance and with these main characteristics: full metal wing, electrically-operated retractable slats, double slotted flaps, extended range, optimized cruise and low-speed flight characteristics, a wide flight envelope and low pilot workload.” (See extensive feature list below.)

According to Zlin’s founder, Pasquale Russo, “The design target was to offer to the market a new version of our plane with improved STOL performance and with these main characteristics: full metal wing, electrically-operated retractable slats, double slotted flaps, extended range, optimized cruise and low-speed flight characteristics, a wide flight envelope and low pilot workload.” (See extensive feature list below.)

The legal issue is not the subject of this article, but now that the matter has successfully been resolved, the Czech producer is back in action and raring to go.

The legal issue is not the subject of this article, but now that the matter has successfully been resolved, the Czech producer is back in action and raring to go. Jet Access

Jet Access John Mauch, Jet Access’ Chief Flight Instructor and Director of Operations said, “We are the 10th largest charter in the world based on flight hours. Jet Access is the only vertically integrated aviation enterprise at a national scale. We do charter, Part 91 jet management, brokerage, FBO management, full service Part 145 MRO, Part 61 and 141 flight training with collegiate program management.”

John Mauch, Jet Access’ Chief Flight Instructor and Director of Operations said, “We are the 10th largest charter in the world based on flight hours. Jet Access is the only vertically integrated aviation enterprise at a national scale. We do charter, Part 91 jet management, brokerage, FBO management, full service Part 145 MRO, Part 61 and 141 flight training with collegiate program management.” “The Evektors are technically advanced aircraft with glass cockpits and autopilots,” echoed John. He added, “This prepares our students for modern piloting that improves safety, while still focusing on stick and rudder skills due to flight characteristics of the Evektors. They’re also larger inside than legacy trainers with far better visibility and cabin airflow.” With airplanes Jet Access has on order for Q3 2022 delivery, they will operate about 80 aircraft, the company elaborated.

“The Evektors are technically advanced aircraft with glass cockpits and autopilots,” echoed John. He added, “This prepares our students for modern piloting that improves safety, while still focusing on stick and rudder skills due to flight characteristics of the Evektors. They’re also larger inside than legacy trainers with far better visibility and cabin airflow.” With airplanes Jet Access has on order for Q3 2022 delivery, they will operate about 80 aircraft, the company elaborated. “The Evektor fleet has amassed over one million flight hours,” Steve Treretola added. “Evektor is built using traditional metal construction, has a fuel burn of four gallons per hour, and has a 2,000-hour engine TBO making it an ideal 21st century successor to the famous trainers of the past including the ubiquitous Cessna 150 and 152 plus the Piper Cherokee series.”

“The Evektor fleet has amassed over one million flight hours,” Steve Treretola added. “Evektor is built using traditional metal construction, has a fuel burn of four gallons per hour, and has a 2,000-hour engine TBO making it an ideal 21st century successor to the famous trainers of the past including the ubiquitous Cessna 150 and 152 plus the Piper Cherokee series.” Evektor has gone far beyond LSA with their four seat Super Cobra (nearby photo) developed some years ago and a twin-engine turboprop regional airliner called EV-55 Outback. These are far outside my coverage of aviation but show the depth of experience and knowledge within Evektor.

Evektor has gone far beyond LSA with their four seat Super Cobra (nearby photo) developed some years ago and a twin-engine turboprop regional airliner called EV-55 Outback. These are far outside my coverage of aviation but show the depth of experience and knowledge within Evektor.

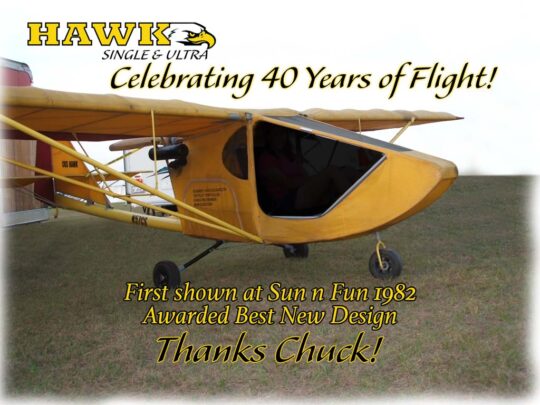

I can remember firsthand when one of aviation’s true characters — Chuck Slusaczyk, of Chuck’s Glider Supplies or CGS — brought his first Hawk to Sun ‘n Fun. As this article illustrates, that was 40 years ago!

I can remember firsthand when one of aviation’s true characters — Chuck Slusaczyk, of Chuck’s Glider Supplies or CGS — brought his first Hawk to Sun ‘n Fun. As this article illustrates, that was 40 years ago!

A longtime friend of the Slusarczyk family, Tim was bound and determined to save Hawk #1 from disintegrating in the Florida sun. “As I understand it,” Bob said, “Tim negotiated with the Museum staff to acquire Hawk #1, so long as it was never flown again, and Tim’s intention was to move the plane to his personal hangar in Florida, with plans for a future renovation.”

A longtime friend of the Slusarczyk family, Tim was bound and determined to save Hawk #1 from disintegrating in the Florida sun. “As I understand it,” Bob said, “Tim negotiated with the Museum staff to acquire Hawk #1, so long as it was never flown again, and Tim’s intention was to move the plane to his personal hangar in Florida, with plans for a future renovation.” “Unfortunately, and tragically, Tim was killed in a light aircraft crash on September 10, 2020, in Sweetwater, Tennessee. Laura was not able to keep the hangar and moved Hawk #1 to a barn at her home.

“Unfortunately, and tragically, Tim was killed in a light aircraft crash on September 10, 2020, in Sweetwater, Tennessee. Laura was not able to keep the hangar and moved Hawk #1 to a barn at her home.

Most of us, including your author, tend to fly only fully-built aircraft while another group of equal size enjoys the building process — or at least this is a more affordable path to airplane ownership.

Most of us, including your author, tend to fly only fully-built aircraft while another group of equal size enjoys the building process — or at least this is a more affordable path to airplane ownership. With a whole stable of handsome aircraft —

With a whole stable of handsome aircraft —  Although Roger scored a superbly-equipped, low-time P2008 (and paid a bit more for it), at least one other for sale, a 2009 model is asking $117,500 in early 2022. Honestly, a used example is a way many pilots could acquire one of these sharp airplanes.

Although Roger scored a superbly-equipped, low-time P2008 (and paid a bit more for it), at least one other for sale, a 2009 model is asking $117,500 in early 2022. Honestly, a used example is a way many pilots could acquire one of these sharp airplanes. Tecnam’s wing for the sleek P2008 is fairly conventional constant-chord shape except for a pinching at the wingroot/fuselage junction. Outboard, the trailing edge is gently tapered with slightly upturned wing tips. Frise ailerons span the outboard sections with discreet slotted flaps inboard. A single lift strut on each side braces the wings to the lower fuselage. On its tail P2008 has a stabilator-style constant-chord tailplane. Its vertical fin is gracefully swept.

Tecnam’s wing for the sleek P2008 is fairly conventional constant-chord shape except for a pinching at the wingroot/fuselage junction. Outboard, the trailing edge is gently tapered with slightly upturned wing tips. Frise ailerons span the outboard sections with discreet slotted flaps inboard. A single lift strut on each side braces the wings to the lower fuselage. On its tail P2008 has a stabilator-style constant-chord tailplane. Its vertical fin is gracefully swept. All Tecnam models are revered for their “natural” handling. This is one of the most straightforward-flying LSA in the fleet. It can function as a capable cross country aircraft or could be used in flight training, though probably not with the turbocharged Rotax 914.

All Tecnam models are revered for their “natural” handling. This is one of the most straightforward-flying LSA in the fleet. It can function as a capable cross country aircraft or could be used in flight training, though probably not with the turbocharged Rotax 914.

When you fly solo you can operate your flying machine the way you want — well… within the laws of physics and the laws of FAA (or whatever national CAA you must obey). What you don’t need to do is worry about a passenger.

When you fly solo you can operate your flying machine the way you want — well… within the laws of physics and the laws of FAA (or whatever national CAA you must obey). What you don’t need to do is worry about a passenger. As of late 2021, we began included kit-built Part 103-type aircraft in our

As of late 2021, we began included kit-built Part 103-type aircraft in our

The Skywheels rotor system is being manufactured again following an 18-year production hiatus. “The Skywheels name has a loyal pilot following with a performance and safety record dating back to 1985.,” reported Joe.

The Skywheels rotor system is being manufactured again following an 18-year production hiatus. “The Skywheels name has a loyal pilot following with a performance and safety record dating back to 1985.,” reported Joe.

Both airplane producer stories made it into mainstream media.

Both airplane producer stories made it into mainstream media.

“At this point, there are about 10 to 12 airframes at the Kherson plant,” Peghiny said to AOPA. “Ordinarily, the airframes would be sent to Flight Design’s final assembly and completion center in the city of Šumperk in the Czech Republic.”

“At this point, there are about 10 to 12 airframes at the Kherson plant,” Peghiny said to AOPA. “Ordinarily, the airframes would be sent to Flight Design’s final assembly and completion center in the city of Šumperk in the Czech Republic.”

“Flight Design employs just under 200 technicians, assemblers, and engineers currently at the Kherson plant,” continued Boatman, “and according to Peghiny, the company has been ramping up that number. ‘We were hiring more aggressively in the past year because of the popularity of the F2, but the other models in the range have been selling well in Europe — simpler, lighter models in particular,’ Tom said.” Of course, Tom refers to the CT-series including CTLS that is one of the most popular LSA in America.

“Flight Design employs just under 200 technicians, assemblers, and engineers currently at the Kherson plant,” continued Boatman, “and according to Peghiny, the company has been ramping up that number. ‘We were hiring more aggressively in the past year because of the popularity of the F2, but the other models in the range have been selling well in Europe — simpler, lighter models in particular,’ Tom said.” Of course, Tom refers to the CT-series including CTLS that is one of the most popular LSA in America. Dave Hirschman wrote, “Dennis Long, a dealer for Aeroprakt… said he spoke with factory officials who said they plan to remain on the job. ‘They told me they’re going to keep making airplanes until they can’t’,” AOPA reported. ‘For the time being, it’s business as usual, although my next two airplanes will likely have to be shipped from Poland because the port of Odessa [in Ukraine] is closed.’”

Dave Hirschman wrote, “Dennis Long, a dealer for Aeroprakt… said he spoke with factory officials who said they plan to remain on the job. ‘They told me they’re going to keep making airplanes until they can’t’,” AOPA reported. ‘For the time being, it’s business as usual, although my next two airplanes will likely have to be shipped from Poland because the port of Odessa [in Ukraine] is closed.’”

Many others might never shut down the engine and soar but are intrigued with efficient cross country flying. In a motorglider, a pilot can be more confident as the aircraft can glide far further than other types, providing a broader safety margin.

Many others might never shut down the engine and soar but are intrigued with efficient cross country flying. In a motorglider, a pilot can be more confident as the aircraft can glide far further than other types, providing a broader safety margin. If

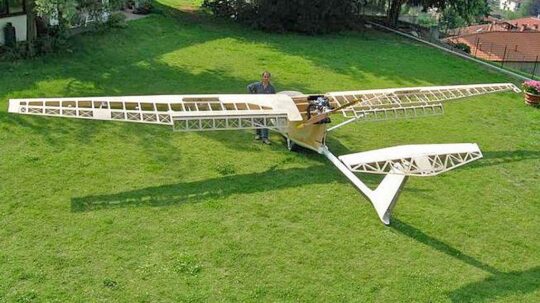

If  Readers who want to save money acquiring a motorglider may finally have a good option: the Piuma Project — composed of five models, the Original, Evolution, Tourer, Twin Evolution, and Almerico. The latter two are two seaters, though Tiziano admits his primary interest is the single place model.

Readers who want to save money acquiring a motorglider may finally have a good option: the Piuma Project — composed of five models, the Original, Evolution, Tourer, Twin Evolution, and Almerico. The latter two are two seaters, though Tiziano admits his primary interest is the single place model. The first flights of the Piuma Original date back to 1990. This was followed with the Tourer.

The first flights of the Piuma Original date back to 1990. This was followed with the Tourer. A Piuma Tourer confirmed the suitability of the name by flying from Venice to Sicily one year (1,250 kilometers or 776 miles) and from Venice to Paris another year (900 kilometers or 560 miles). These flights confirm, Tiziano said, “that even with a small motorglider, I can do great trips.”

A Piuma Tourer confirmed the suitability of the name by flying from Venice to Sicily one year (1,250 kilometers or 776 miles) and from Venice to Paris another year (900 kilometers or 560 miles). These flights confirm, Tiziano said, “that even with a small motorglider, I can do great trips.” “Construction time depends on the builder’s meticulousness,” said Tiziano. “Normally, about 1,000 hours are sufficient for a person with limited woodworking experience to complete the work. Plans are composed of large technical sheets (24 x 40 inches) with lots of details.”

“Construction time depends on the builder’s meticulousness,” said Tiziano. “Normally, about 1,000 hours are sufficient for a person with limited woodworking experience to complete the work. Plans are composed of large technical sheets (24 x 40 inches) with lots of details.” A “Project Book” is not necessary for the normal builder, but it is very important for those who want to know the project better. The Project Book contains design considerations; lots of drawings of the fuselage, wings, tail, and more; structural calculations; plus flying characteristics and speeds.

A “Project Book” is not necessary for the normal builder, but it is very important for those who want to know the project better. The Project Book contains design considerations; lots of drawings of the fuselage, wings, tail, and more; structural calculations; plus flying characteristics and speeds. Professional build centers have been highlighted as one of Mosaic’s many aspects. Everyone including FAA recognizes that kits built with oversight from people who know the aircraft and the process of construction makes for better, safer airplanes. Because safety is FAA’s main consideration, professional builder-assist centers are expected to part of the new regulation. I have been predicting we will see the NPRM by Oshkosh 2022 (mere months away now).

Professional build centers have been highlighted as one of Mosaic’s many aspects. Everyone including FAA recognizes that kits built with oversight from people who know the aircraft and the process of construction makes for better, safer airplanes. Because safety is FAA’s main consideration, professional builder-assist centers are expected to part of the new regulation. I have been predicting we will see the NPRM by Oshkosh 2022 (mere months away now).

Beside importing aircraft to the USA and helping customers build them, Chip experimented with

Beside importing aircraft to the USA and helping customers build them, Chip experimented with  Zigolo Mg21 starts out with multiple versions, mainly differences in wings and wing controls.

Zigolo Mg21 starts out with multiple versions, mainly differences in wings and wing controls. Mg21’s central structure is a lower box beam running from an aerodynamically-shaped nose containing a digital instrument panel to a tubular empennage boom. In the center of the structure, two rectangular box-section beams support a fixed center wing section and the engine.

Mg21’s central structure is a lower box beam running from an aerodynamically-shaped nose containing a digital instrument panel to a tubular empennage boom. In the center of the structure, two rectangular box-section beams support a fixed center wing section and the engine. Flight testing is ongoing but stall speeds are estimated at 63 kilometers per hour or 34 knots for the short wing, 60 km/h (32 knots) for the long wing, and 52 km/h (28 knots) for the long wing with flap. Francesco will need to slow it another 4 knots to meet

Flight testing is ongoing but stall speeds are estimated at 63 kilometers per hour or 34 knots for the short wing, 60 km/h (32 knots) for the long wing, and 52 km/h (28 knots) for the long wing with flap. Francesco will need to slow it another 4 knots to meet  “For the USA market, I’m sure we can have a 55 knot cruise speed with climb at 800-900 feet per minute plus the easy-fold system (nearby photo), and a competitive price for an advanced [quick-build-type] kit. Due to very small pack size, we can use air shipment. I’m working with DHL to have worldwide fast shipment without the expensive container charges. I worked very hard to keep all measures inside the maximum permitted by DHL” Given numerous reports of container shipment costs rising by double, triple, or even more, air shipment might ironically turn out to be cheaper for such a cleverly-packaged product.

“For the USA market, I’m sure we can have a 55 knot cruise speed with climb at 800-900 feet per minute plus the easy-fold system (nearby photo), and a competitive price for an advanced [quick-build-type] kit. Due to very small pack size, we can use air shipment. I’m working with DHL to have worldwide fast shipment without the expensive container charges. I worked very hard to keep all measures inside the maximum permitted by DHL” Given numerous reports of container shipment costs rising by double, triple, or even more, air shipment might ironically turn out to be cheaper for such a cleverly-packaged product. “Accessories, engine, and instruments are included in the kit but will be shipped separately,” said Francesco. “A customer will receive the airframe kit with all necessary to start the work, and a second shipment will bring the accessories.

“Accessories, engine, and instruments are included in the kit but will be shipped separately,” said Francesco. “A customer will receive the airframe kit with all necessary to start the work, and a second shipment will bring the accessories. Please keep in mind these prices are subject to change given supply problems affecting all industries. “In any case, I will state an offering price for each batch of airplanes because the prices change on all materials,” said Francesco. A first batch of 10 kits will be offered at close to the prices mentioned above but

Please keep in mind these prices are subject to change given supply problems affecting all industries. “In any case, I will state an offering price for each batch of airplanes because the prices change on all materials,” said Francesco. A first batch of 10 kits will be offered at close to the prices mentioned above but

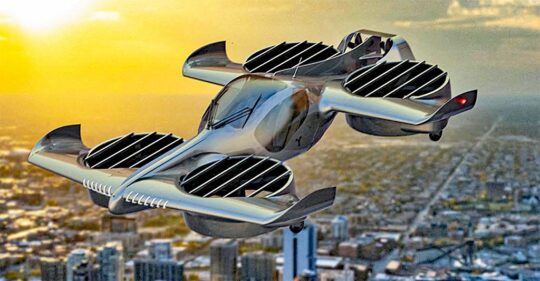

I still would not follow one multicopter article with another except for developer Doron Merdinger, saying this, “Suggested [selling price is] $135,000 to $150,000.” That got my attention. From what I’ve seen so far, any eVTOL larger/heavier than a Part 103 entry is way, way more expensive.

I still would not follow one multicopter article with another except for developer Doron Merdinger, saying this, “Suggested [selling price is] $135,000 to $150,000.” That got my attention. From what I’ve seen so far, any eVTOL larger/heavier than a Part 103 entry is way, way more expensive. No one commenting on Jetson One or the other Part 103

No one commenting on Jetson One or the other Part 103

Safety is addressed with features such as: programmed emergency landing protocols, an energy-dissipating body, multiple redundancies, air bag, ballistic parachute, and multiple anti-collision sensors. H1 is, Doroni explains, “a smart vehicle with advanced electronics, GPS, laser [range finders], cameras, a barometer, and accelerometers.”

Safety is addressed with features such as: programmed emergency landing protocols, an energy-dissipating body, multiple redundancies, air bag, ballistic parachute, and multiple anti-collision sensors. H1 is, Doroni explains, “a smart vehicle with advanced electronics, GPS, laser [range finders], cameras, a barometer, and accelerometers.” Ducted fans are also quieter than propellers: they shield the blade noise and reduce the intensity of the tip vortices. This is important for neighbor relations (especially when your unusual aircraft will also attract more than a usual share of attention).

Ducted fans are also quieter than propellers: they shield the blade noise and reduce the intensity of the tip vortices. This is important for neighbor relations (especially when your unusual aircraft will also attract more than a usual share of attention).

In this article, I’ll explore only such aircraft that might be called recreational. Interestingly, these developers have discovered Part 103 and are using it to get their aircraft to market. Like them or not, you have to admit these people are creative and driven. We should expect to see more of this.

In this article, I’ll explore only such aircraft that might be called recreational. Interestingly, these developers have discovered Part 103 and are using it to get their aircraft to market. Like them or not, you have to admit these people are creative and driven. We should expect to see more of this. Reports

Reports

“The elementary design features an open chassis that means the Jetson One is only suitable for operations in fair weather conditions. It has eight sets of electric motors and rotors, and is fitted with a whole-aircraft recovery parachute,” wrote FutureFlight.aero.

“The elementary design features an open chassis that means the Jetson One is only suitable for operations in fair weather conditions. It has eight sets of electric motors and rotors, and is fitted with a whole-aircraft recovery parachute,” wrote FutureFlight.aero. If you want to join what may be millions of teen-aged boys on their smartphones, here’s a link to a whole series of videos on Jetson One:

If you want to join what may be millions of teen-aged boys on their smartphones, here’s a link to a whole series of videos on Jetson One: