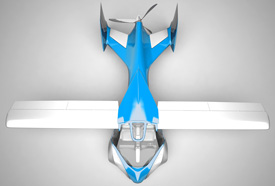

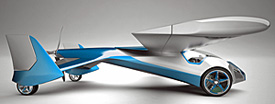

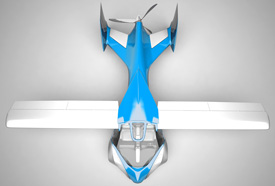

One of the several reasons I like living in Florida (besides no snow this time of year) is the close proximity of all kinds of aviation businesses. The central Florida town of Tavares, about 45 minutes northwest of Orlando, is home to not one but two light seaplane factories. The city named itself “America’s Seaplane City.” Last Friday, we visited both manufacturers ending our tour at the SeaRey Open House (photo). Owner Adam Yang said they had 13 SeaRey aircraft fly in despite windy conditions. Their handsome facility was full of people including many owner/builders, potential customers, friends, and the media (me). The day turned out to be pleasant and we got to watch several SeaRey aircraft taxi down the launch ramp into the lake and take off not 50 yards away. One of these was the new 914 SeaRey SLSA; more on that below.

A couple years ago Progressive Aerodyne took the plunge and elected to pursue Special Light-Sport Aircraft acceptance so they could address a part of the market they never could seek: fully built SeaRey aircraft.

One of the several reasons I like living in Florida (besides no snow this time of year) is the close proximity of all kinds of aviation businesses. The central Florida town of Tavares, about 45 minutes northwest of Orlando, is home to not one but two light seaplane factories. The city named itself “America’s Seaplane City.” Last Friday, we visited both manufacturers ending our tour at the SeaRey Open House (photo). Owner Adam Yang said they had 13 SeaRey aircraft fly in despite windy conditions. Their handsome facility was full of people including many owner/builders, potential customers, friends, and the media (me). The day turned out to be pleasant and we got to watch several SeaRey aircraft taxi down the launch ramp into the lake and take off not 50 yards away. One of these was the new 914 SeaRey SLSA; more on that below.

A couple years ago Progressive Aerodyne took the plunge and elected to pursue Special Light-Sport Aircraft acceptance so they could address a part of the market they never could seek: fully built SeaRey aircraft.New SeaRey Exhibits Plenty of Get Up & Go

Adam Yang (right) hosting the Progressive Aerodyne open house.

Consultant Abid Farooqui shows where SeaRey engineers used plenty of carbon fiber to reduce weight 60 pounds!

The fully faired Rotax 914 engine on the new SeaRey SLSA.

One of the several reasons I like living in Florida (besides no snow this time of year) is the close proximity of all kinds of aviation businesses. The central Florida town of Tavares, about 45 minutes northwest of Orlando, is home to not one but two light seaplane factories. The city named itself “America’s Seaplane City.” Last Friday, we visited both manufacturers ending our tour at the SeaRey Open House (photo). Owner Adam Yang said they had 13 SeaRey aircraft fly in despite windy conditions. Their handsome facility was full of people including many owner/builders, potential customers, friends, and the media (me). The day turned out to be pleasant and we got to watch several SeaRey aircraft taxi down the launch ramp into the lake and take off not 50 yards away. One of these was the new 914 SeaRey SLSA; more on that below.

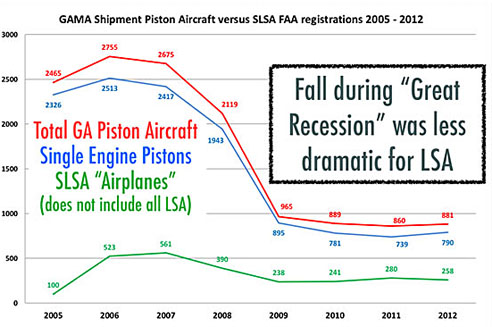

A couple years ago Progressive Aerodyne took the plunge and elected to pursue Special Light-Sport Aircraft acceptance so they could address a part of the market they never could seek: fully built SeaRey aircraft. Last fall, the company a major benchmark as they successfully passed their first-ever FAA audit. Most companies get a few gigs (officially: “findings”) and have to fix them (“corrections”). Mostly this seems to be paperwork but sometime the manufacturing process isn’t up to regulatory review so more work is needed. The SeaRey producer got a clean bill of health before FAA inspectors left the building; subsequently, high-ranking FAA officials were effusive in their praise for Progressive Aerodyne’s accomplishment. Such things are a team effort by definition, but leading compliance task force was Florida engineer, Abid Farooqui. At the open house, Abid was generous to explain some of what went into the latest 914 turbo SeaRey SLSA project.

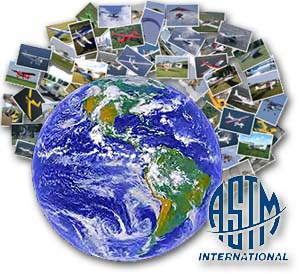

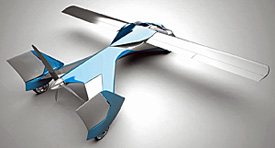

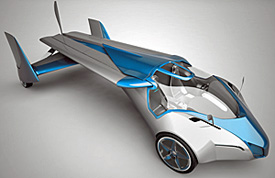

What really stood out for me was this: “We took 60 pounds out of the airframe to make SLSA seaplane weight,” reported Abid. I’m not an engineer but I’ve been around plenty of development projects and can state that taking 60 pounds from an airframe that weighs less than 1,000 is a huge accomplishment. Companies meeting ASTM standards have to build an airplane that meets empty weight calculations. For SeaRey, this figure is 980 pounds empty and the 115-horsepower, fully engine cowled Rotax 914 turbocharged SeaRey makes the numbers. The weight savings came through many big and small tweaks but a significant share came from use of carbon fiber in the hull and other parts of the airplane. Abid continued as a consulting engineer after the 2012 ASTM compliance and FAA acceptance push. He offers engineering services under the business name SilverLight Aviation. Abid has also volunteered assistance LAMA, the Light Aircraft Manufacturers Association in the updating of the organization ASTM compliance checklists available to member producers.

The LSA seaplane sub-sector continues to amaze me. I’ve written about this often as so many intriguing designs are on the market or coming to market. Businesses like Progressive Aerodyne would seem well positioned with seasoned, field-tested products. Newcomers bring slick designs and fresh features but have to convince the market. All will compete somewhat on price and the SeaRey is in good shape again. You can get a kit SeaRey in the air for around $70-80,000 and plenty of prior builders are available to offer assistance. Alternatively you can go to Tavares, Florida and work in the factory with experts available to answer questions. Those with thicker wallets and less time can get the top-of-the-line 914 SeaRey SLSA for $150,000. Given that other LSA seaplanes are quoting $189,000, a 914 SeaRey for a hundred and fifty grand is quite a value in a powerful, proven aircraft. In the video below, original designer and SeaRey pilot extraordinaire Kerry Richter, shows the short water run of the new model with added horsepower.

One of the several reasons I like living in Florida (besides no snow this time of year) is the close proximity of all kinds of aviation businesses. The central Florida town of Tavares, about 45 minutes northwest of Orlando, is home to not one but two light seaplane factories. The city named itself “America’s Seaplane City.” Last Friday, we visited both manufacturers ending our tour at the SeaRey Open House (photo). Owner Adam Yang said they had 13 SeaRey aircraft fly in despite windy conditions. Their handsome facility was full of people including many owner/builders, potential customers, friends, and the media (me). The day turned out to be pleasant and we got to watch several SeaRey aircraft taxi down the launch ramp into the lake and take off not 50 yards away. One of these was the new 914 SeaRey SLSA; more on that below.

A couple years ago Progressive Aerodyne took the plunge and elected to pursue Special Light-Sport Aircraft acceptance so they could address a part of the market they never could seek: fully built SeaRey aircraft.

One of the several reasons I like living in Florida (besides no snow this time of year) is the close proximity of all kinds of aviation businesses. The central Florida town of Tavares, about 45 minutes northwest of Orlando, is home to not one but two light seaplane factories. The city named itself “America’s Seaplane City.” Last Friday, we visited both manufacturers ending our tour at the SeaRey Open House (photo). Owner Adam Yang said they had 13 SeaRey aircraft fly in despite windy conditions. Their handsome facility was full of people including many owner/builders, potential customers, friends, and the media (me). The day turned out to be pleasant and we got to watch several SeaRey aircraft taxi down the launch ramp into the lake and take off not 50 yards away. One of these was the new 914 SeaRey SLSA; more on that below.

A couple years ago Progressive Aerodyne took the plunge and elected to pursue Special Light-Sport Aircraft acceptance so they could address a part of the market they never could seek: fully built SeaRey aircraft.