Tabor Coates calls his business Blue Collar Aviation. Honestly, as someone who scours the globe for affordable aircraft, any business with this name was certain to grab my attention. This isn’t simply adroit marketing. Tabor’s Maynard, Massachusetts operation is deep into affordable aviation. How affordable? Tabor’s most-expensive offering is the SkyRanger Nynja (featured in this 2023 article and this flight report). With every item needed in the kit to include engine, instruments and coverings that need no paint, this tried-and-true light aircraft sells for $65,000 and that even includes freight from across the Atlantic.* How deep into affordable goes Tabor? He offers two versions of SkyRanger — Swift III and Nynja — with a complete kit for the former starting at $49,985. If that’s still high for your budget Tabor offers FlyLight’s line of superlight (nanolight?) weight-shift trikes. The simplest of these flying machines are ready-to-fly for around $15,000.

Your labor investment will be about 300 hours. Here's how Tabor Coates broke down my inquiry about build time: "We (he and partner, Chance Parker) logged 330 hours over nine months but we took our time assembling our demo aircraft. Plus, we had other projects at the time so we worked on it when we could."

How long might it take you? "It could be done in six months still going at it part-time," Tabor continued. "However, we have some reports of an experienced builder getting it done in a single month; that's working full-time and bringing an aptitude for such work."

Your labor investment will be about 300 hours. Here's how Tabor Coates broke down my inquiry about build time: "We (he and partner, Chance Parker) logged 330 hours over nine months but we took our time assembling our demo aircraft. Plus, we had other projects at the time so we worked on it when we could."

How long might it take you? "It could be done in six months still going at it part-time," Tabor continued. "However, we have some reports of an experienced builder getting it done in a single month; that's working full-time and bringing an aptitude for such work."

Nynja designers moved the fuel from behind the seat in Swift to two wings tanks holding 31.5 gallons of fuel along with a header tank behind the seats. This change "allowed more baggage aft of the seat, taking better advantage of Nynja's big useful load," noted Tabor.

Nynja also cruises a bit faster than Swift. "We can easily cruise 100 miles per hour burning 4.1 gallons per hour," Tabor reported. "If we push up to 5300 rpm, we see 105."

With 100 horsepower and Kanardia instruments a Nynja kit is $65,000 in the USA. That number includes freight from overseas; shipping in the USA by truck would be extra.

FlyLight's production backlog is six months. In early 2024, that is fairly fast. When challenged, Tabor replied, "That's real! And yes, they are still built in Ukraine, as they have been for decades." Fully fabricated airframes are shipped to FlyLight Airsports in the UK where they finish each aircraft before packaging for shipment to Blue Collar in Massachusetts.

Nynja designers moved the fuel from behind the seat in Swift to two wings tanks holding 31.5 gallons of fuel along with a header tank behind the seats. This change "allowed more baggage aft of the seat, taking better advantage of Nynja's big useful load," noted Tabor.

Nynja also cruises a bit faster than Swift. "We can easily cruise 100 miles per hour burning 4.1 gallons per hour," Tabor reported. "If we push up to 5300 rpm, we see 105."

With 100 horsepower and Kanardia instruments a Nynja kit is $65,000 in the USA. That number includes freight from overseas; shipping in the USA by truck would be extra.

FlyLight's production backlog is six months. In early 2024, that is fairly fast. When challenged, Tabor replied, "That's real! And yes, they are still built in Ukraine, as they have been for decades." Fully fabricated airframes are shipped to FlyLight Airsports in the UK where they finish each aircraft before packaging for shipment to Blue Collar in Massachusetts.

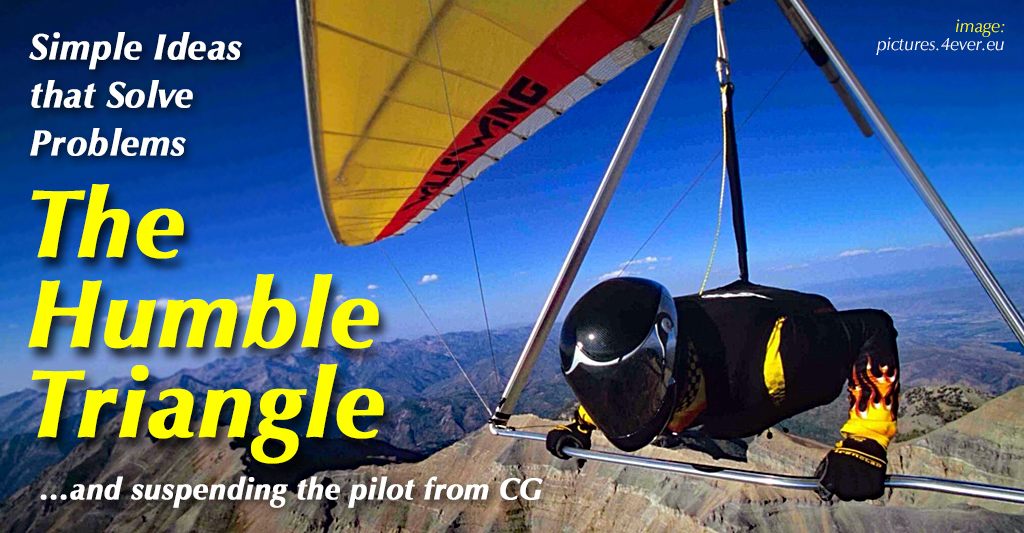

Possible trike pilots divide into two groups: hang glider pilots who love the idea of a self-launch capability, or… fixed wing pilots open-minded enough to give one of these a try. Most won't take the opportunity but for someone who enjoys motorcycling or water thrill craft, trikes might work for you.

Let me be direct: With the least-costly trike Tabor sells, you could be airborne for around $15,000 without any building (or FAA pilot license) required. You may want more but that's a price that can meet most budgets.

Possible trike pilots divide into two groups: hang glider pilots who love the idea of a self-launch capability, or… fixed wing pilots open-minded enough to give one of these a try. Most won't take the opportunity but for someone who enjoys motorcycling or water thrill craft, trikes might work for you.

Let me be direct: With the least-costly trike Tabor sells, you could be airborne for around $15,000 without any building (or FAA pilot license) required. You may want more but that's a price that can meet most budgets.

In England very light-weight aircraft are called "Sub-70 (kilograms)" and "SSDR." I've often

In England very light-weight aircraft are called "Sub-70 (kilograms)" and "SSDR." I've often  "The 9 (Nine) is coming to Sun 'n Fun 2024," exclaimed Tabor, speaking about the newest trike from FlyLight (see below).

If you are willing to look at weight shift but uncertain about training, read the sidebar at the bottom of this article. This is from text for an upcoming article Tabor authored for

"The 9 (Nine) is coming to Sun 'n Fun 2024," exclaimed Tabor, speaking about the newest trike from FlyLight (see below).

If you are willing to look at weight shift but uncertain about training, read the sidebar at the bottom of this article. This is from text for an upcoming article Tabor authored for  "

" A pivotal moment occurred a couple of years ago when I engaged in a conversation with a paramotor instructor friend about training. I noticed that some paramotors were now equipped with wheels and used for tandem instruction. Upon inquiry, my friend revealed that they had obtained an FAA exemption by removing the term "foot-launched" from their regulations, allowing the use of wheels. To my surprise, the exemption specified that it was granted for training in a two-place powered paraglider or powered hang glider. However, the training vehicle could have two seats but must adhere to the definition of a Part 103 ultralight in all other aspects.

This revelation prompted me to explore the possibility of building a Powered Hang Glider trainer weighing less than 254 pounds. A thorough web search led me to discover the La Mouette Samson, a trike that has served as a trainer in Europe for the past decade. La Mouette, a trusted name with numerous innovations in the weight-shift trike and hang glider world, caught my attention. With a Samson trike soon to arrive, I plan to showcase it at Sun 'n Fun in April. To validate the viability of this initiative, I consulted Jim Stephenson at Aero Sports Connection, who enthusiastically affirmed the potential to train ultralight instructors as we did in the past. This approach will likely attract quality instructors capable of producing safe powered hang glider (PHG) pilots.

The timing couldn't be more opportune, considering the growing popularity of powered hang gliders in Europe. Companies like Flylight Airsports in the UK have played a pivotal role, introducing design innovations that make these aircraft lighter, easily transportable by car, and more capable overall.

—Tabor Coates

AFI: PHG. CFI: Airplane, Weight-Shift Control Land & Sea, Gyroplane.

Blue Collar Aviation

flybluecollar@gmail.com

(978) 273-7460

A pivotal moment occurred a couple of years ago when I engaged in a conversation with a paramotor instructor friend about training. I noticed that some paramotors were now equipped with wheels and used for tandem instruction. Upon inquiry, my friend revealed that they had obtained an FAA exemption by removing the term "foot-launched" from their regulations, allowing the use of wheels. To my surprise, the exemption specified that it was granted for training in a two-place powered paraglider or powered hang glider. However, the training vehicle could have two seats but must adhere to the definition of a Part 103 ultralight in all other aspects.

This revelation prompted me to explore the possibility of building a Powered Hang Glider trainer weighing less than 254 pounds. A thorough web search led me to discover the La Mouette Samson, a trike that has served as a trainer in Europe for the past decade. La Mouette, a trusted name with numerous innovations in the weight-shift trike and hang glider world, caught my attention. With a Samson trike soon to arrive, I plan to showcase it at Sun 'n Fun in April. To validate the viability of this initiative, I consulted Jim Stephenson at Aero Sports Connection, who enthusiastically affirmed the potential to train ultralight instructors as we did in the past. This approach will likely attract quality instructors capable of producing safe powered hang glider (PHG) pilots.

The timing couldn't be more opportune, considering the growing popularity of powered hang gliders in Europe. Companies like Flylight Airsports in the UK have played a pivotal role, introducing design innovations that make these aircraft lighter, easily transportable by car, and more capable overall.

—Tabor Coates

AFI: PHG. CFI: Airplane, Weight-Shift Control Land & Sea, Gyroplane.

Blue Collar Aviation

flybluecollar@gmail.com

(978) 273-7460 A few sources confirmed $1,000 is a common fee. Don't get me wrong. I'm not saying a check ride isn't worth that much; it's merely a bigger number than expected, although my young pilot friend still has to come up with that amount of dough. Whew!

When friends and family complain about grocery store prices or the cost of air travel, I shrug and say, "Tell me something that has not gone up by 50 or 100% in the last three years." No one loves the situation but those are economic facts. The cost of everything is up, a lot. Why would a Private check ride not be subject to the same market forces?

A few sources confirmed $1,000 is a common fee. Don't get me wrong. I'm not saying a check ride isn't worth that much; it's merely a bigger number than expected, although my young pilot friend still has to come up with that amount of dough. Whew!

When friends and family complain about grocery store prices or the cost of air travel, I shrug and say, "Tell me something that has not gone up by 50 or 100% in the last three years." No one loves the situation but those are economic facts. The cost of everything is up, a lot. Why would a Private check ride not be subject to the same market forces?

To finish an airplane in Spain for this year's show in Lakeland, the team must make sure everything is right, prepare TrueLite for shipment, cross the ocean, pass Customs, get it delivered locally, and finally get it checked out and ready for close examination at Sun 'n Fun. All that needs to happen in 10 weeks. I'm telling you after many years of reporting such developments — that will be a challenge.

Aviad owner and TrueLite designer Francesco Di Martino proceeded this rush of activity with more of his own. He relocated his production facility, established operations at the new quarters and has produced a TrueLite for American debut in his new facility (nearby images).

To finish an airplane in Spain for this year's show in Lakeland, the team must make sure everything is right, prepare TrueLite for shipment, cross the ocean, pass Customs, get it delivered locally, and finally get it checked out and ready for close examination at Sun 'n Fun. All that needs to happen in 10 weeks. I'm telling you after many years of reporting such developments — that will be a challenge.

Aviad owner and TrueLite designer Francesco Di Martino proceeded this rush of activity with more of his own. He relocated his production facility, established operations at the new quarters and has produced a TrueLite for American debut in his new facility (nearby images).

On a recent trip to Spain, Chip expressed, "I checked out Francesco's new long wing with slotted flaps installed on the TrueLite in Spain." He also noted the improved wing tip, saying, "Francesco is waiting on good flying weather for the test flights." After this last modification is proved, the plan is for that aircraft to travel across the Atlantic Ocean to Sun 'n Fun.

"TrueLite has electric flaps operating twin teleflex cables," Chip added. "The control and flap indicator will be on the instrument panel. And, TrueLite's wings still fold in under two minutes by a single person!"

"Come see this cool ultralight at Sun 'n Fun this April," Chip urged!

On a recent trip to Spain, Chip expressed, "I checked out Francesco's new long wing with slotted flaps installed on the TrueLite in Spain." He also noted the improved wing tip, saying, "Francesco is waiting on good flying weather for the test flights." After this last modification is proved, the plan is for that aircraft to travel across the Atlantic Ocean to Sun 'n Fun.

"TrueLite has electric flaps operating twin teleflex cables," Chip added. "The control and flap indicator will be on the instrument panel. And, TrueLite's wings still fold in under two minutes by a single person!"

"Come see this cool ultralight at Sun 'n Fun this April," Chip urged!

"The engine is working great! …and I was able to reduce fuel consumption to 5 liters hour (about 1.25 gallons per hour) at a lower cruise speed but I can maintain the same 95-100 kilometers per hour (59-63 miles per hour) at same rpm as before with the shorter wing!

"I'm sure that once people test TrueLite, they'll love it. It's incredibly safe at any speed and with any flap angle. It practically eliminates the risk of accidental stall.

"Last, I put [TrueLite] on scales yesterday. It weighed 114 kilograms (251 pounds) so even a parachute is not required to stay legal [although adding the parachute adds no weight penalty].

"I'll take some time to write a blog post on my page and share all my thoughts (see Aviad link above)."

"The engine is working great! …and I was able to reduce fuel consumption to 5 liters hour (about 1.25 gallons per hour) at a lower cruise speed but I can maintain the same 95-100 kilometers per hour (59-63 miles per hour) at same rpm as before with the shorter wing!

"I'm sure that once people test TrueLite, they'll love it. It's incredibly safe at any speed and with any flap angle. It practically eliminates the risk of accidental stall.

"Last, I put [TrueLite] on scales yesterday. It weighed 114 kilograms (251 pounds) so even a parachute is not required to stay legal [although adding the parachute adds no weight penalty].

"I'll take some time to write a blog post on my page and share all my thoughts (see Aviad link above)."

Check these one-of-a-kind offerings:

Check these one-of-a-kind offerings:

Like everything on this website, all these features are free for the using (although email is requested to use PlaneFinder 2.0). I hope you'll go explore this website thoroughly. The good folks at Flying Media that acquired this content in March 2023 have promised to keep thousands of articles and tens of thousands of photos available.

Like everything on this website, all these features are free for the using (although email is requested to use PlaneFinder 2.0). I hope you'll go explore this website thoroughly. The good folks at Flying Media that acquired this content in March 2023 have promised to keep thousands of articles and tens of thousands of photos available.

Mosaic as a completed regulation is still 16 months away, according to FAA's oft-repeated statements about how long they need after comments have closed. The agency has a lot of work remaining on this proposed regulation.

After a group of maintenance organizations asked for more time, FAA extended the comment period to January 22, 2024. That means you have less than one week left as this article is posted. After that, FAA begins huddling internally to review all comments and make other changes (and hopefully fix a number of weak areas;

Mosaic as a completed regulation is still 16 months away, according to FAA's oft-repeated statements about how long they need after comments have closed. The agency has a lot of work remaining on this proposed regulation.

After a group of maintenance organizations asked for more time, FAA extended the comment period to January 22, 2024. That means you have less than one week left as this article is posted. After that, FAA begins huddling internally to review all comments and make other changes (and hopefully fix a number of weak areas;  Beside FAA,

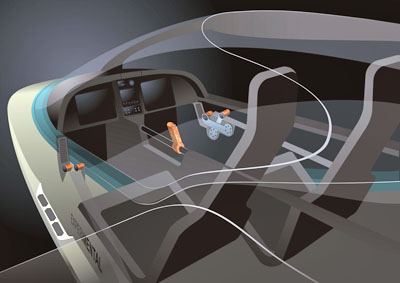

Beside FAA,  GoGetAir's G750 evolved from an aircraft I had seen earlier in Europe called One (image). A stylish design One used a sports car approach, two rear seats of limited carrying capacity. One Aircraft was designed by Iztok Šalamon after he began that company in 2014. One Aircraft shut down operations in 2019 when GoGetAir was established.

Today, GoGetAir and their G750 are today the product of Ania and Iztok Šalamo (nearby image). They are well positioned for the coming Mosaic LSA class.

GoGetAir's G750 evolved from an aircraft I had seen earlier in Europe called One (image). A stylish design One used a sports car approach, two rear seats of limited carrying capacity. One Aircraft was designed by Iztok Šalamon after he began that company in 2014. One Aircraft shut down operations in 2019 when GoGetAir was established.

Today, GoGetAir and their G750 are today the product of Ania and Iztok Šalamo (nearby image). They are well positioned for the coming Mosaic LSA class.

"We took the things that we love and we have built on them," noted the couple. "The result is the innovative GoGetAir line of aircraft. In order to achieve the best possible comfort for the pilot during G750's nine-hour endurance, the aircraft is equipped with adjustable rudder pedals as well as with adjustable seats and three different foam density of seat cushioning for maximum comfort."

"GoGetAir is the only aircraft in the category that features large forward-and-upward-hinging doors for easy entry," said the Šalamos, referring to them as "Lamborghini-style doors." They added, "Pilot and passengers are protected with a Formula-1-like full-carbon roll cage with kevlar protection.

"In addition, every G750 is equipped with a BRS Parachute System," GoGetAir said, "designed around a solid-fuel rocket housed in the front fuselage that pulls the parachute to full deployment within seconds."

"We took the things that we love and we have built on them," noted the couple. "The result is the innovative GoGetAir line of aircraft. In order to achieve the best possible comfort for the pilot during G750's nine-hour endurance, the aircraft is equipped with adjustable rudder pedals as well as with adjustable seats and three different foam density of seat cushioning for maximum comfort."

"GoGetAir is the only aircraft in the category that features large forward-and-upward-hinging doors for easy entry," said the Šalamos, referring to them as "Lamborghini-style doors." They added, "Pilot and passengers are protected with a Formula-1-like full-carbon roll cage with kevlar protection.

"In addition, every G750 is equipped with a BRS Parachute System," GoGetAir said, "designed around a solid-fuel rocket housed in the front fuselage that pulls the parachute to full deployment within seconds."

Europe-based light aviation journalist

Europe-based light aviation journalist

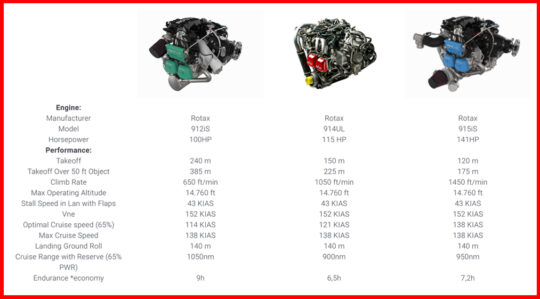

Now, GoGetAir offers the turbocharged, intercooled

Now, GoGetAir offers the turbocharged, intercooled  With Rotax 915, G750 takes off in less tha 400 feet of ground roll and can climb 1,500 feet per minute. Max cruising at altitude, G750/915 will burn 6-7 gallons per hour. Under ideal conditions, full tanks of 35 gallons offers range of nearly 1,000 nautical miles.

"Due to its huge flaps G750 is easily operated on 1,500 foot runway," said GoGetAir. Stall speed for all three engine sizes is a modest 43 knots or 49 miles per hour. With Mosaic coming in at 54 knots (or possibly faster) G750 is well within Mosaic parameters.

With Rotax 915, G750 takes off in less tha 400 feet of ground roll and can climb 1,500 feet per minute. Max cruising at altitude, G750/915 will burn 6-7 gallons per hour. Under ideal conditions, full tanks of 35 gallons offers range of nearly 1,000 nautical miles.

"Due to its huge flaps G750 is easily operated on 1,500 foot runway," said GoGetAir. Stall speed for all three engine sizes is a modest 43 knots or 49 miles per hour. With Mosaic coming in at 54 knots (or possibly faster) G750 is well within Mosaic parameters.

The timing of Scissortail and GoGetAir is excellent, with only 16 months or so before Mosaic is released. In the meantime, FAA has registration categories such Experimental Exhibition that allow import of a small number of fully-assembled aircraft to test the market.

By the second quarter of 2025, Mosaic should become official regulation and then G750 will easily fit the mLSA category assuming the company chooses to pursue and declare compliance with ASTM standards.

The timing of Scissortail and GoGetAir is excellent, with only 16 months or so before Mosaic is released. In the meantime, FAA has registration categories such Experimental Exhibition that allow import of a small number of fully-assembled aircraft to test the market.

By the second quarter of 2025, Mosaic should become official regulation and then G750 will easily fit the mLSA category assuming the company chooses to pursue and declare compliance with ASTM standards.

G750 is a costlier choice as will be many mLSA. At $270,000 to $340,000, depending on optional equipment and finishes, G750 is helping to define a price point for Mosaic LSA. Extra seats and extra capabilities cost real money.

While we all wait on Mosaic, Scissortail can refine their operation and deliver a few Experimental Exhibition aircraft to earn feedback from American pilots. Contact Shannon or Alan for more or to arrange a flight demo.

G750 is a costlier choice as will be many mLSA. At $270,000 to $340,000, depending on optional equipment and finishes, G750 is helping to define a price point for Mosaic LSA. Extra seats and extra capabilities cost real money.

While we all wait on Mosaic, Scissortail can refine their operation and deliver a few Experimental Exhibition aircraft to earn feedback from American pilots. Contact Shannon or Alan for more or to arrange a flight demo.

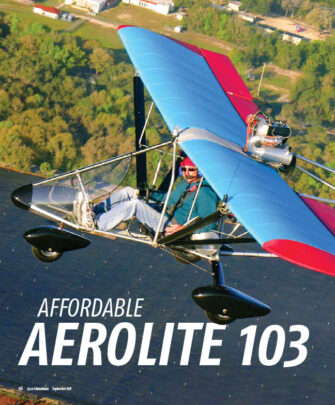

While you can't get this one any longer, about 20 are flying and some pop up on aviation sale listings. In its day — before Valley Engineering decided to cease building and focus on their Culver (wood) Prop enterprise — Back Yard Flyer attracted wide interest, rising steadily to be one of our Top 50 videos of about 1,000 produced.

Part of the reason for keen interest was an airframe that quickly folded in a unique for easier storage. Built primarily of welded aluminum, the airplane looked tough yet managed to stay within Part 103 tight constraints.

While you can't get this one any longer, about 20 are flying and some pop up on aviation sale listings. In its day — before Valley Engineering decided to cease building and focus on their Culver (wood) Prop enterprise — Back Yard Flyer attracted wide interest, rising steadily to be one of our Top 50 videos of about 1,000 produced.

Part of the reason for keen interest was an airframe that quickly folded in a unique for easier storage. Built primarily of welded aluminum, the airplane looked tough yet managed to stay within Part 103 tight constraints.

Another reason for strong interest in this simple flying machine was its four-stroke engine, modified from a Generac engine. At the time, 2010 or so, four stroke on genuine Part 103 ultralights was extremely rare.

Put together, the welded aluminum structure with its folding wing and dependable power and, presto, you have Backyard Flyer.

Another reason for strong interest in this simple flying machine was its four-stroke engine, modified from a Generac engine. At the time, 2010 or so, four stroke on genuine Part 103 ultralights was extremely rare.

Put together, the welded aluminum structure with its folding wing and dependable power and, presto, you have Backyard Flyer.

I refer to "the Flying Farmer," Gene Smith. Every year it seemed he would bring a new variation of something he casually called his backyard flyer. One year, after being challenged by weather the prior year, Gene decided not to fly to Oshkosh. With help from his son Larry, Gene created the current last iteration of the Back Yard Flyer seen in nearby images.

The particular sound people remember was a four stroke power plant. By itself, that was very unusual 10 or 15 years ago yet what made it unique was that Valley engineering started with a Generac-brand power generator engine, modified it significantly, and ended with a four stroke engine that could be used on this very light airframe and qualify for Part 103.

I refer to "the Flying Farmer," Gene Smith. Every year it seemed he would bring a new variation of something he casually called his backyard flyer. One year, after being challenged by weather the prior year, Gene decided not to fly to Oshkosh. With help from his son Larry, Gene created the current last iteration of the Back Yard Flyer seen in nearby images.

The particular sound people remember was a four stroke power plant. By itself, that was very unusual 10 or 15 years ago yet what made it unique was that Valley engineering started with a Generac-brand power generator engine, modified it significantly, and ended with a four stroke engine that could be used on this very light airframe and qualify for Part 103.

I never weighed the finished and I'll be it was close to the line but Gene and Larry said it weighed "251 pounds even with tricycle gear." One reason why it looks heavier than allowed is the larger-diameter welded tubing that comprises most of Back Yard Flyer. Most observers are fooled because you expect welded to be steel (generally thinner diameter tubes). Welded aluminum is relatively unusual but the Smiths report it made a robust airframe able to handle the bigger engine.

I never weighed the finished and I'll be it was close to the line but Gene and Larry said it weighed "251 pounds even with tricycle gear." One reason why it looks heavier than allowed is the larger-diameter welded tubing that comprises most of Back Yard Flyer. Most observers are fooled because you expect welded to be steel (generally thinner diameter tubes). Welded aluminum is relatively unusual but the Smiths report it made a robust airframe able to handle the bigger engine.

Gene proved the naysayers wrong back in the early 2010s — yes, pilots complained about the cost of airplanes then, too. His Backyard Flyer could qualify for Part 103 and could be purchased for less than $20,000. In early 2024, an equivalent amount of dollars would price Back Yard Flyer at $28,000. and for that, most would consider it a bargain.

Gene, the "Flying Farmer," faithfully flew his circuits of the Ultralight Area pattern accented by a throaty, guttural four-stroke sound that did not mimic the ubiquitous Rotax 582 that was king in the day. Gene's Generac made an energetic flyer that could easily get in and out of a generous back yards.

Gene proved the naysayers wrong back in the early 2010s — yes, pilots complained about the cost of airplanes then, too. His Backyard Flyer could qualify for Part 103 and could be purchased for less than $20,000. In early 2024, an equivalent amount of dollars would price Back Yard Flyer at $28,000. and for that, most would consider it a bargain.

Gene, the "Flying Farmer," faithfully flew his circuits of the Ultralight Area pattern accented by a throaty, guttural four-stroke sound that did not mimic the ubiquitous Rotax 582 that was king in the day. Gene's Generac made an energetic flyer that could easily get in and out of a generous back yards.

"After Grandpa (Gene) passed away in 2016," Alaina Lewis wrote, "we decided we couldn’t offer adequate customer support for the plane. We still have all the tooling and jigs and have no plans to sell the design. We will continue to offer customer support for anyone who has a Back Yard Flyer or any of our engines."

"We appreciate all the support that has been shown for our little plane through the years," Alaina wrote in 2019. "Grandpa loved designing and building and we were so grateful for the opportunity to get a few planes out into the aviation world and the opportunity for him to live out his aviation dream."

She continues the family enterprise making beautiful wood props.

"After Grandpa (Gene) passed away in 2016," Alaina Lewis wrote, "we decided we couldn’t offer adequate customer support for the plane. We still have all the tooling and jigs and have no plans to sell the design. We will continue to offer customer support for anyone who has a Back Yard Flyer or any of our engines."

"We appreciate all the support that has been shown for our little plane through the years," Alaina wrote in 2019. "Grandpa loved designing and building and we were so grateful for the opportunity to get a few planes out into the aviation world and the opportunity for him to live out his aviation dream."

She continues the family enterprise making beautiful wood props.

Just six years ago, I interviewed

Just six years ago, I interviewed

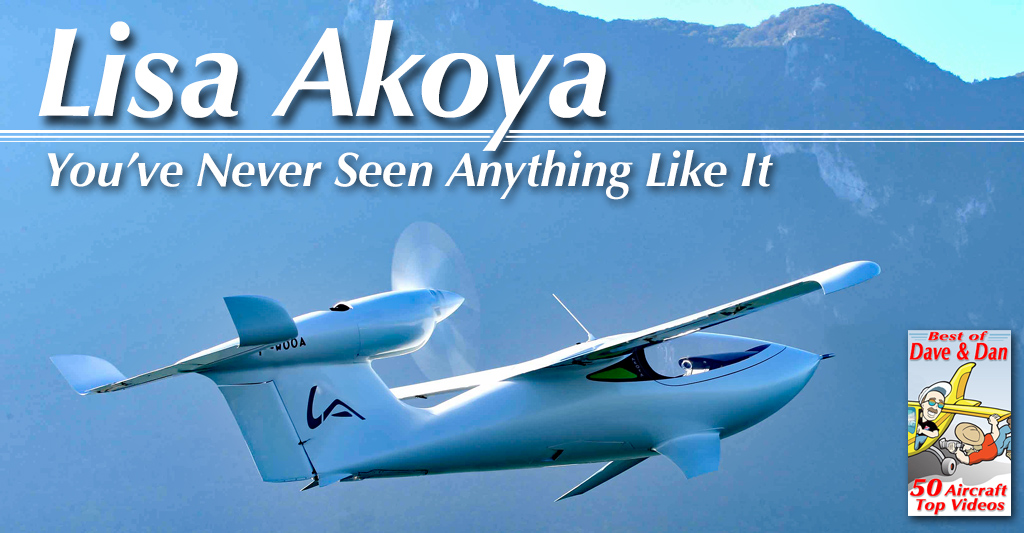

No wonder," exclaimed some! More than a decade back, they approached a retail price of $400,000. After ten years of dollar inflation, that number would be way past $500,000 today.

Remarkable as it may be to those of us with normal incomes, buyers for high-end products seem often to emerge. Cirrus and their steady sales of million-dollar-plus four seaters is proof of that. To appeal to such well-heeled pilots, a company better deliver a beautiful, functional, well-supported aircraft. Doing that expertly at a premium level gets expensive.

No wonder," exclaimed some! More than a decade back, they approached a retail price of $400,000. After ten years of dollar inflation, that number would be way past $500,000 today.

Remarkable as it may be to those of us with normal incomes, buyers for high-end products seem often to emerge. Cirrus and their steady sales of million-dollar-plus four seaters is proof of that. To appeal to such well-heeled pilots, a company better deliver a beautiful, functional, well-supported aircraft. Doing that expertly at a premium level gets expensive.

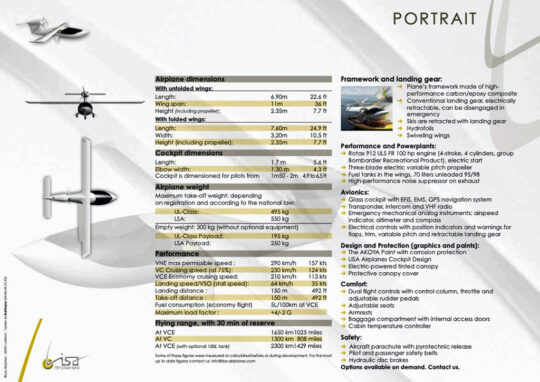

“From the cockpit to the wingtips through the Seafoils, a number of technical innovations offer elegance, operating convenience, and exceptional aerodynamic performance," claimed Lisa. They promoted a top speed of 156 miles per hour (135 knots), range of 1,250 miles, with fuel consumption of 4.2 gallons per hour. "Akoya takes off and lands in as little as 650 feet,” they said (full specs on image below).

Arguably, one of the most distinctive design aspects of Akoya is its tailfin-mounted, forward-facing Rotax engine. Others have done something similar (Equator is

“From the cockpit to the wingtips through the Seafoils, a number of technical innovations offer elegance, operating convenience, and exceptional aerodynamic performance," claimed Lisa. They promoted a top speed of 156 miles per hour (135 knots), range of 1,250 miles, with fuel consumption of 4.2 gallons per hour. "Akoya takes off and lands in as little as 650 feet,” they said (full specs on image below).

Arguably, one of the most distinctive design aspects of Akoya is its tailfin-mounted, forward-facing Rotax engine. Others have done something similar (Equator is  Thanks to folding wings (photo & video), Akoya could be stored in a garage or, if you happen to run in more elite circles, perhaps aboard your yacht. With its then-stratospheric price tag of $395,000, Lisa had to appeal to very well-heeled customers, including yacht owners one supposes.

Lisa developers boasted Akoya’s 180-degree panoramic view through its tinted bubble canopy and a cockpit specially designed to combine both aesthetics and comfort. The cockpit is 51.6 inches wide, spacious even compared to the largest LSA.

Thanks to folding wings (photo & video), Akoya could be stored in a garage or, if you happen to run in more elite circles, perhaps aboard your yacht. With its then-stratospheric price tag of $395,000, Lisa had to appeal to very well-heeled customers, including yacht owners one supposes.

Lisa developers boasted Akoya’s 180-degree panoramic view through its tinted bubble canopy and a cockpit specially designed to combine both aesthetics and comfort. The cockpit is 51.6 inches wide, spacious even compared to the largest LSA.

My longtime videographer and LSA seaplane expert, Dave Loveman described Akoya as "…an LSA featuring unique 'Seafoils' which it uses for taking off from water. Akoya is amphibious, with a retractable landing gear that can be equipped to take off or land from land, water, or snow."

Dave also observed, "Akoya has cantilever wings, which can be folded for ease of storage or trailering. Akoya uses all carbon-fiber construction, with metal parts produced from titanium. Seating is side by side, with dual controls, flaps, and a center mounted throttle, and adjustable rudder pedals. Power is supplied by a Rotax 912 ULS or iS engine."

My longtime videographer and LSA seaplane expert, Dave Loveman described Akoya as "…an LSA featuring unique 'Seafoils' which it uses for taking off from water. Akoya is amphibious, with a retractable landing gear that can be equipped to take off or land from land, water, or snow."

Dave also observed, "Akoya has cantilever wings, which can be folded for ease of storage or trailering. Akoya uses all carbon-fiber construction, with metal parts produced from titanium. Seating is side by side, with dual controls, flaps, and a center mounted throttle, and adjustable rudder pedals. Power is supplied by a Rotax 912 ULS or iS engine."

Longtime aviation journalist James Lawrence wrote, "Some bright minds at Lisa Airplanes, a French company, had a great idea to take the hydrofoil concept and apply it to an LSA seaplane. I’d often wondered why hydrofoils haven’t been done before; it’s such a great concept."

"The technology for the entire package is patented and called Multi-Access," Jim continued, "not the most compelling name but what the hey, look at how cool those little moustache water wings look sticking out from the hull!l

Longtime aviation journalist James Lawrence wrote, "Some bright minds at Lisa Airplanes, a French company, had a great idea to take the hydrofoil concept and apply it to an LSA seaplane. I’d often wondered why hydrofoils haven’t been done before; it’s such a great concept."

"The technology for the entire package is patented and called Multi-Access," Jim continued, "not the most compelling name but what the hey, look at how cool those little moustache water wings look sticking out from the hull!l

"Seafoil is a trademarked name, which adds a little more marketing sizzle to this steak. They’re connected to a retractable gear that can be rigged with wheels or skis, and also to motor-driven, pivoting wings."

To prevent pilot error in re-assembling a folded-wing Akoya, designers added an ignition interlock system, position indicators, and a wing position locking system." Folding wings have strong appeal but add complexity that demands more oversight and/or a religiously-followed checklist.

"Seafoil is a trademarked name, which adds a little more marketing sizzle to this steak. They’re connected to a retractable gear that can be rigged with wheels or skis, and also to motor-driven, pivoting wings."

To prevent pilot error in re-assembling a folded-wing Akoya, designers added an ignition interlock system, position indicators, and a wing position locking system." Folding wings have strong appeal but add complexity that demands more oversight and/or a religiously-followed checklist.

Jim concluded his remarks, "This is a 'luxury amphibian' with sexy hydrofoil wings on its futuristic hull. It’s priced sky-high at $395,000. Like the equally costly Icon A5, Akoya is sleek, stylish, and downright gorgeous."

In February of 2013, our friends at AVweb uncovered news that Akoya would be acquired by investors in China. A trend was underway ten years ago, leading large Chinese businesses to purchase several famous aviation brands including Continental Motors, Cirrus, and Mooney, among others. AVweb went on to report, "According to French and Chinese online sources, production will remain in France." Unfortunately, Akoya never built another aircraft.

Jim concluded his remarks, "This is a 'luxury amphibian' with sexy hydrofoil wings on its futuristic hull. It’s priced sky-high at $395,000. Like the equally costly Icon A5, Akoya is sleek, stylish, and downright gorgeous."

In February of 2013, our friends at AVweb uncovered news that Akoya would be acquired by investors in China. A trend was underway ten years ago, leading large Chinese businesses to purchase several famous aviation brands including Continental Motors, Cirrus, and Mooney, among others. AVweb went on to report, "According to French and Chinese online sources, production will remain in France." Unfortunately, Akoya never built another aircraft.

The big Chinese money disappeared from aviation some years ago. As Lisa and their Akoya never made another appearance, this appears to be another design lost to history though long experience in this industry has taught me never to assume a good design is forever gone. Worthy designs have often re-emerged.

The experience gained by the two French developers of Akoya could influence downstream designs in the way aviation has done since before the Wright brothers.

The big Chinese money disappeared from aviation some years ago. As Lisa and their Akoya never made another appearance, this appears to be another design lost to history though long experience in this industry has taught me never to assume a good design is forever gone. Worthy designs have often re-emerged.

The experience gained by the two French developers of Akoya could influence downstream designs in the way aviation has done since before the Wright brothers.

Thanks for your interest in Light Sport Aircraft (LSA) and, coming some time in 2025, aircraft that will comply with the new Mosaic rules — as well as the expansion of Sport Pilot privileges. A lot is happening here in 2025 and we'll keep you up with events!

Thanks for your interest in Light Sport Aircraft (LSA) and, coming some time in 2025, aircraft that will comply with the new Mosaic rules — as well as the expansion of Sport Pilot privileges. A lot is happening here in 2025 and we'll keep you up with events!

Right before Christmas, read about the maiden flight of Junkers side-by-side A60, a year-end recap provided by Icon Aircraft, and year highlights from leading engine producer Rotax Aircraft Engines. Let's get started…

Right before Christmas, read about the maiden flight of Junkers side-by-side A60, a year-end recap provided by Icon Aircraft, and year highlights from leading engine producer Rotax Aircraft Engines. Let's get started…

"The style and fun factor of the A60 is enhanced by the new retractable undercarriage, the nose wheel and the fact that the pilot and passenger sit next to each other," continued Junkers. "With two different versions, a closed cabin and an open cockpit, the A60 offers a versatility that will delight pilots and aviation enthusiasts alike. Side by side it´s a celebration of freedom and a shared passion for flying."

Junkers A60 uses a 100-horsepower Rotax 912iS engine and features

"The style and fun factor of the A60 is enhanced by the new retractable undercarriage, the nose wheel and the fact that the pilot and passenger sit next to each other," continued Junkers. "With two different versions, a closed cabin and an open cockpit, the A60 offers a versatility that will delight pilots and aviation enthusiasts alike. Side by side it´s a celebration of freedom and a shared passion for flying."

Junkers A60 uses a 100-horsepower Rotax 912iS engine and features  The company continues to make progress after the global upset that came with Covid-induced shipping delays (and sky rocketing costs). "We are still quoting 8-10 months for deliveries," said Marc, though that figure is lower than most airframe producers are quoting in late 2023, so Rotax in Austria is catching up with orders.

"We are seeing lots of flight school activity," added Marc. He noted large producers like Tecnam and BRM Aero (Bristell) have order times exceeding two years for some models.

The company continues to make progress after the global upset that came with Covid-induced shipping delays (and sky rocketing costs). "We are still quoting 8-10 months for deliveries," said Marc, though that figure is lower than most airframe producers are quoting in late 2023, so Rotax in Austria is catching up with orders.

"We are seeing lots of flight school activity," added Marc. He noted large producers like Tecnam and BRM Aero (Bristell) have order times exceeding two years for some models.

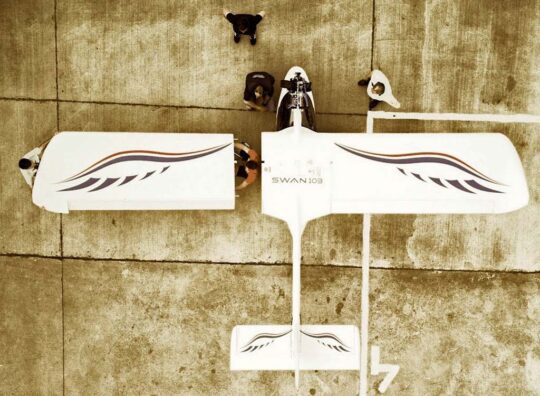

LE for Lowered Engine

LE for Lowered Engine While a nearby image shows how smoothly an electric motor fit on the older Swan, now all that hardware can be tucked inside the nose for reduced drag. AVI already has good experience with the electric for those interested in that option.

While a nearby image shows how smoothly an electric motor fit on the older Swan, now all that hardware can be tucked inside the nose for reduced drag. AVI already has good experience with the electric for those interested in that option.

Not a Kit

Not a Kit

Normally at Mt. Vernon, "It's all about the airplanes!" It will again be so come September 5-7, 2024 — more on that below.

However, in April 2024, here comes something different and special for pilots at Mt. Vernon.

Normally at Mt. Vernon, "It's all about the airplanes!" It will again be so come September 5-7, 2024 — more on that below.

However, in April 2024, here comes something different and special for pilots at Mt. Vernon.

Same Great Benefits

Same Great Benefits For 2024, the Mt. Vernon Expo will operate its 16th year. That exceeds the run the Sebring Sport Aviation Expo had — 15 years from 2004-2019 — making Midwest LSA Expo the longest-running Light-Sport event in the world.

Airport manager Chris Collins, his staff, and a small army of hard-working volunteers have made Mt. Vernon such a welcoming event that many vendors have attended every single year.

For 2024, the Mt. Vernon Expo will operate its 16th year. That exceeds the run the Sebring Sport Aviation Expo had — 15 years from 2004-2019 — making Midwest LSA Expo the longest-running Light-Sport event in the world.

Airport manager Chris Collins, his staff, and a small army of hard-working volunteers have made Mt. Vernon such a welcoming event that many vendors have attended every single year.

Midwest LSA Expo was the one-and-only event to happen in 2020. The good crowds that attended were very grateful Chris and group made the effort during that otherwise rather terrifying year.

For 2024, the 16th annual running will take place on Septmeber 5-6-7, 2024. I hope you can attend…

Midwest LSA Expo was the one-and-only event to happen in 2020. The good crowds that attended were very grateful Chris and group made the effort during that otherwise rather terrifying year.

For 2024, the 16th annual running will take place on Septmeber 5-6-7, 2024. I hope you can attend…  We feel the Midwest LSA Expo is the most convenient and affordable of its type in the country. The host City and Airport are located at the crossroads of two major interstates and are 1 hour, 15 minutes by ground from Lambert St. Louis International Airport. Over 1,200 hotel rooms and 60 restaurants are within three miles of the event site. Over 50% of the entire U.S. population is within an eight-hour drive from Mt. Vernon!

The infrastructure of the host airport (KMVN) is impressive, and includes the following amenities: 6,500 foot by 150 foot main runway, five precision approaches including ILS, 9.25 acres of concrete ramp space, Class “E” airspace, and ARFF Index A safety. Event organizers have placed all aircraft exhibitor spaces on the main ramp with easy ingress and egress for demo flights.

We feel the Midwest LSA Expo is the most convenient and affordable of its type in the country. The host City and Airport are located at the crossroads of two major interstates and are 1 hour, 15 minutes by ground from Lambert St. Louis International Airport. Over 1,200 hotel rooms and 60 restaurants are within three miles of the event site. Over 50% of the entire U.S. population is within an eight-hour drive from Mt. Vernon!

The infrastructure of the host airport (KMVN) is impressive, and includes the following amenities: 6,500 foot by 150 foot main runway, five precision approaches including ILS, 9.25 acres of concrete ramp space, Class “E” airspace, and ARFF Index A safety. Event organizers have placed all aircraft exhibitor spaces on the main ramp with easy ingress and egress for demo flights.

Midwest LSA Expo. Inc. specifically created the event to educate aviators about all facets related to the LSA industry including the many different aircraft types, available engines, and LSA performance; promote the sale of LSA’s, the use of LSA aircraft for flight training and in rental fleets; and promote economic development in the southern Illinois region.

Midwest LSA Expo. Inc. specifically created the event to educate aviators about all facets related to the LSA industry including the many different aircraft types, available engines, and LSA performance; promote the sale of LSA’s, the use of LSA aircraft for flight training and in rental fleets; and promote economic development in the southern Illinois region.

Fellow Australians (and showmen) Bill Bennett and Bill Moyes grabbed Dickenson's triangular bar with the pilot suspended behind it and took it much further but their success selling tens of thousands of hang gliders rode fully on Dickenson's innovation.

"I just see John Dickenson's triangle control bar and pilot suspension as a meaningful catalyst that provided a way… a thread to how hang gliding and its leaders — Thevenot, Peghiny, and others — branched into weight-shift trikes and other ultralights and ultralights in-turn to Light-Sport to our current segment of sport flying," Malcolm concluded.

Fellow Australians (and showmen) Bill Bennett and Bill Moyes grabbed Dickenson's triangular bar with the pilot suspended behind it and took it much further but their success selling tens of thousands of hang gliders rode fully on Dickenson's innovation.

"I just see John Dickenson's triangle control bar and pilot suspension as a meaningful catalyst that provided a way… a thread to how hang gliding and its leaders — Thevenot, Peghiny, and others — branched into weight-shift trikes and other ultralights and ultralights in-turn to Light-Sport to our current segment of sport flying," Malcolm concluded.

But isn't flying for hire prohibited in Part 103? Yes, it is.

However, "public use" aircraft do not have to meet FAA aircraft certification regulations nor operating limitations. "Public use" can include activities like police, fire, rescue, border patrol, and similar typically government functions whether provided by federal, state, or local agencies. In short, government departments at all levels get special privileges.

But isn't flying for hire prohibited in Part 103? Yes, it is.

However, "public use" aircraft do not have to meet FAA aircraft certification regulations nor operating limitations. "Public use" can include activities like police, fire, rescue, border patrol, and similar typically government functions whether provided by federal, state, or local agencies. In short, government departments at all levels get special privileges.

After six years of development, testing, and now entering production, Lift announced, "Hexa is now available for sale to public agencies." The company said that five production Hexa aircraft are allocated to new public agency partners who opt in soon after the announcement.

"With use cases spanning police, fire, medical, search and rescue, emergency, and disaster response," Lift stated, "your agency can be among the very first to leverage electric, vertical takeoff and landing (eVTOL) aircraft to serve your agency’s mission.

After six years of development, testing, and now entering production, Lift announced, "Hexa is now available for sale to public agencies." The company said that five production Hexa aircraft are allocated to new public agency partners who opt in soon after the announcement.

"With use cases spanning police, fire, medical, search and rescue, emergency, and disaster response," Lift stated, "your agency can be among the very first to leverage electric, vertical takeoff and landing (eVTOL) aircraft to serve your agency’s mission.

Aero Asia show producers are the same team who puts on a favorite European show,

Aero Asia show producers are the same team who puts on a favorite European show,

Aero Asia plans a successive trade fair for November 2025, skipping a year as is common for such events outside the United States.

Aero Asia plans a successive trade fair for November 2025, skipping a year as is common for such events outside the United States.

Since 2014, LAMA has explained that light aircraft could be used productively for many work missions, although the Association was careful to stress that it was not advocating for passenger or cargo hauling. Many other aerial working activities were demonstrated to FAA. Agency rule writers agreed and the opportunity is coming with Mosaic.

Admittedly, the community does not yet have all the information needed on what pilot credentials will be required to use Mosaic LSA for aerial work, but as the agency weighs comments and discusses this internally, we hope Flight Standards (which manages such things) will remain as reasonable as the Aircraft Certification group.

Since 2014, LAMA has explained that light aircraft could be used productively for many work missions, although the Association was careful to stress that it was not advocating for passenger or cargo hauling. Many other aerial working activities were demonstrated to FAA. Agency rule writers agreed and the opportunity is coming with Mosaic.

Admittedly, the community does not yet have all the information needed on what pilot credentials will be required to use Mosaic LSA for aerial work, but as the agency weighs comments and discusses this internally, we hope Flight Standards (which manages such things) will remain as reasonable as the Aircraft Certification group.

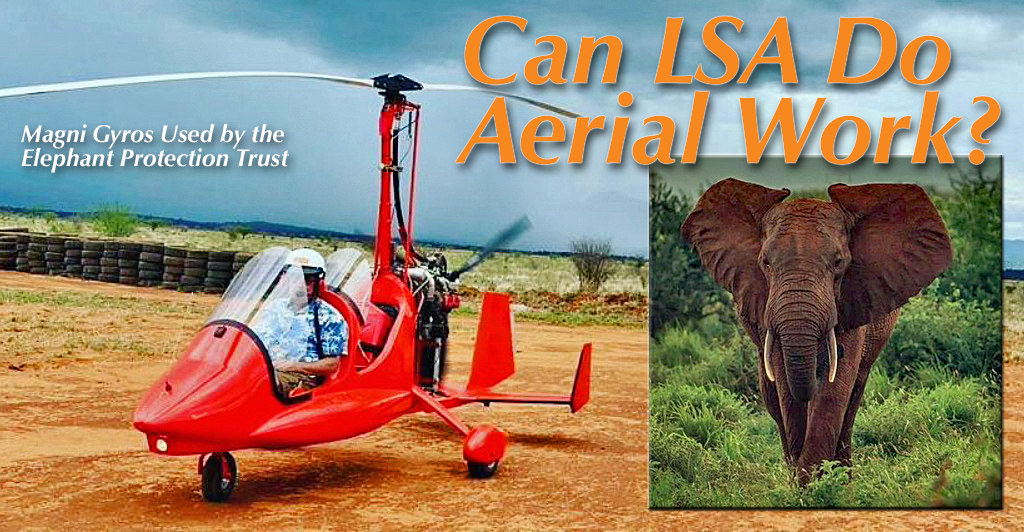

In this article I am pleased to observe one credible use of an LSA to do some serious aerial work. Fortunately, many other countries already recognize these flying machines can be useful. In this story, learn how the freedom to fly is helping Africa's wildlife thanks to gyroplane enthusiasts.

In this article I am pleased to observe one credible use of an LSA to do some serious aerial work. Fortunately, many other countries already recognize these flying machines can be useful. In this story, learn how the freedom to fly is helping Africa's wildlife thanks to gyroplane enthusiasts.

"As you know, flying gyros is a beautiful hobby shared by many people all over the world. For some people, however, this hobby has become an important job with a big role in the protection and defense of wildlife.

"A great example is given by our friend Keith Hellyer who dedicates his life to fight every day against poachers with his fleet of three M24 Orion gyros and one M22 Voyager in the Tsavo’s Kasigau corridor in Kenya. The aircraft are used to monitor elephant movements, acting as deterrent against poachers and pinpointing the presence of intruders so that ranger patrols on the ground can be directed towards them.

"The M24 Orion (side-by-side, enclosed) in particular has proven to be a valid ally in this important task, allowing rapid travel and immediate intervention.

"As you know, flying gyros is a beautiful hobby shared by many people all over the world. For some people, however, this hobby has become an important job with a big role in the protection and defense of wildlife.

"A great example is given by our friend Keith Hellyer who dedicates his life to fight every day against poachers with his fleet of three M24 Orion gyros and one M22 Voyager in the Tsavo’s Kasigau corridor in Kenya. The aircraft are used to monitor elephant movements, acting as deterrent against poachers and pinpointing the presence of intruders so that ranger patrols on the ground can be directed towards them.

"The M24 Orion (side-by-side, enclosed) in particular has proven to be a valid ally in this important task, allowing rapid travel and immediate intervention.

"Happily, this is not the longer the only example," MagniGyro continued.

"A new luxuriant green M16 Tandem Trainer (nearby image) was recently approved by the CAA and is aimed to be used to fly around in the Shamwari Game Resort, a 30,000 hectare game reserve situated in the heart of the Eastern Cape in South Africa.

"Here is the largest population of private free-roaming black and white rhino animals in South Africa.

"Safari Operation Manager Andrew Kearney is working hand-in-hand with instructor Caroline Zalewsky Blane to bring the gyro from Johannesburg to Port Elizabeth in an exciting two-day trip," said the Trust. "The new gyro will assist the rangers in supervising these fascinating animals during the regular surveillance of the reserve."

"Happily, this is not the longer the only example," MagniGyro continued.

"A new luxuriant green M16 Tandem Trainer (nearby image) was recently approved by the CAA and is aimed to be used to fly around in the Shamwari Game Resort, a 30,000 hectare game reserve situated in the heart of the Eastern Cape in South Africa.

"Here is the largest population of private free-roaming black and white rhino animals in South Africa.

"Safari Operation Manager Andrew Kearney is working hand-in-hand with instructor Caroline Zalewsky Blane to bring the gyro from Johannesburg to Port Elizabeth in an exciting two-day trip," said the Trust. "The new gyro will assist the rangers in supervising these fascinating animals during the regular surveillance of the reserve."

Appreciation Expressed:

Appreciation Expressed:  "A big thank you to Magnigyro for their continued partnership, and keeping our gyrocopters durable and safe," expressed the Trust. "We recently received two sets of rotor blades (nearby image) that will ensure our gyrocopters are well suited for a multitude of tasks."

"A big thank you to Magnigyro for their continued partnership, and keeping our gyrocopters durable and safe," expressed the Trust. "We recently received two sets of rotor blades (nearby image) that will ensure our gyrocopters are well suited for a multitude of tasks."

Aerial work is helpful because a manufacturer that can sell some units for a commercial purpose may sell these work machines at a higher profit margin. In turn, this should strengthen their business, helping to ensure they can continue to provide parts and service for the airplane you bought from them.

Healthier businesses can support their customers better. That alone makes the effort worthwhile. These aircraft perform useful activities while consuming less fuel and making less noise, bringing further benefits to the idea of aerial work.

Aerial work is helpful because a manufacturer that can sell some units for a commercial purpose may sell these work machines at a higher profit margin. In turn, this should strengthen their business, helping to ensure they can continue to provide parts and service for the airplane you bought from them.

Healthier businesses can support their customers better. That alone makes the effort worthwhile. These aircraft perform useful activities while consuming less fuel and making less noise, bringing further benefits to the idea of aerial work.

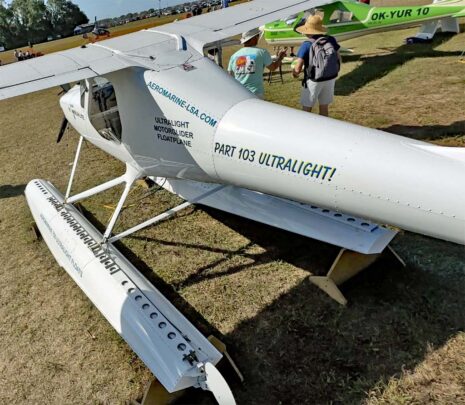

"TrueLite is a fresh new ultralight design with a very nice feature that the wing can be folded for transport in only two minutes. This feature is huge as hangars are not only difficult to find but very expensive." Any pilot seeking hangar space almost anywhere is aware Chip is right. "TrueLite owners can roll their aircraft up on a small custom trailer for transport to their home garage," Chip finished.

He identified that TrueLite's folding wings open up many possibilities like:

"TrueLite is a fresh new ultralight design with a very nice feature that the wing can be folded for transport in only two minutes. This feature is huge as hangars are not only difficult to find but very expensive." Any pilot seeking hangar space almost anywhere is aware Chip is right. "TrueLite owners can roll their aircraft up on a small custom trailer for transport to their home garage," Chip finished.

He identified that TrueLite's folding wings open up many possibilities like:

"To better meet the Part 103 parameters, Aeromarine has commissioned Aviad to build a longer wing with large slotted flaps incorporated. This new wing will also increase the endurance on our planned electric-powered version," Chip ventured.

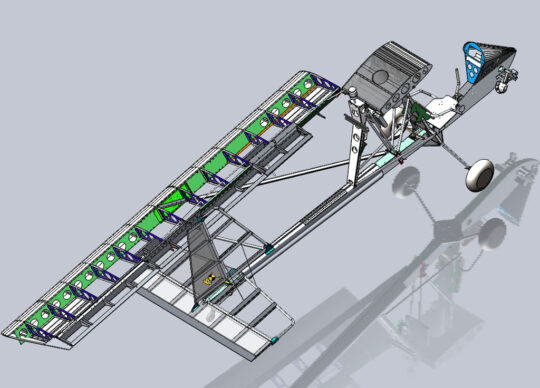

"I am here working side-by-side with Francesco to make this first prototype wing. Francesco has completed the design in SolidWorks 3D software," Chip observed. "We are then cutting and bending and assembling the parts to assure perfect match-hole fit and finish. We have just completed the new flaps and now are preparing the wing and spar parts. In the next few days the wing will be assembled."

"To better meet the Part 103 parameters, Aeromarine has commissioned Aviad to build a longer wing with large slotted flaps incorporated. This new wing will also increase the endurance on our planned electric-powered version," Chip ventured.

"I am here working side-by-side with Francesco to make this first prototype wing. Francesco has completed the design in SolidWorks 3D software," Chip observed. "We are then cutting and bending and assembling the parts to assure perfect match-hole fit and finish. We have just completed the new flaps and now are preparing the wing and spar parts. In the next few days the wing will be assembled."

"Then we will install the new wings on the original TrueLite for a series of test flights. Once verified and proven, we will build a new airframe for the wing. This completely new TrueLite will be the first production model and will be shipped to Florida in time for flight demos and display at

"Then we will install the new wings on the original TrueLite for a series of test flights. Once verified and proven, we will build a new airframe for the wing. This completely new TrueLite will be the first production model and will be shipped to Florida in time for flight demos and display at  "In addition to our aircraft kits, we now offer fully assembled aircraft," he finished.

TrueLite can meet common European regulations such as Germany's 120-Kilo Class or UK's SSDR. Many European nations handle what they call ultralights (with gross weights about 1,000 pounds) via country-by-country regulation, where LSA types increasingly follow EU-wide EASA regulations.

In the USA, Florida-based Aeromarine-LSA will assemble TrueLites in their collaboration with Paul Mather's M-Squared operation in Alabama (

"In addition to our aircraft kits, we now offer fully assembled aircraft," he finished.

TrueLite can meet common European regulations such as Germany's 120-Kilo Class or UK's SSDR. Many European nations handle what they call ultralights (with gross weights about 1,000 pounds) via country-by-country regulation, where LSA types increasingly follow EU-wide EASA regulations.

In the USA, Florida-based Aeromarine-LSA will assemble TrueLites in their collaboration with Paul Mather's M-Squared operation in Alabama (

Powered parachute, or PPC, enthusiasts are their own breed, some say. Maybe so, but how is that different than, say, seaplanes or floatplanes, motorgliders, weight-shift trikes, gyroplanes, or hang gliders? Each of these segments also enjoys a loyal following.

Indeed, as Powrachute owner Galen Geigley states in the video below, more than 8,000 powered parachutes are flying in the USA. The high-volume sales from two decades back may have matured but a substantial number of pilots ended up loving their PPCs.

Powered parachute, or PPC, enthusiasts are their own breed, some say. Maybe so, but how is that different than, say, seaplanes or floatplanes, motorgliders, weight-shift trikes, gyroplanes, or hang gliders? Each of these segments also enjoys a loyal following.

Indeed, as Powrachute owner Galen Geigley states in the video below, more than 8,000 powered parachutes are flying in the USA. The high-volume sales from two decades back may have matured but a substantial number of pilots ended up loving their PPCs.

Based in Hastings, Michigan,

Based in Hastings, Michigan,

Powrachute delivers a lot of aircraft for the money. In 2023, the high-end AirWolf 912 sells for thousands less than the average price of a new car despite the latter being built by the hundreds of thousands.

Powrachute delivers a lot of aircraft for the money. In 2023, the high-end AirWolf 912 sells for thousands less than the average price of a new car despite the latter being built by the hundreds of thousands.

He also sold more new powered parachutes than any other dealer for Powrachute, the largest manufacturer in the sport (certificate image). Finally, his YouTube channel emphasizing powered parachute flying obtained more subscribers than anyone else in the niche.

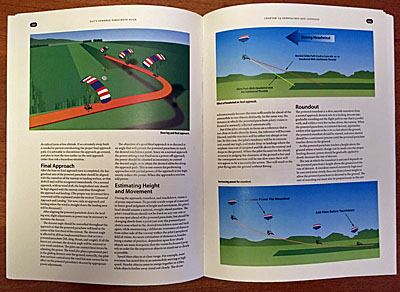

He continues to work on improving training in the sport by working on a second edition to his book (

He also sold more new powered parachutes than any other dealer for Powrachute, the largest manufacturer in the sport (certificate image). Finally, his YouTube channel emphasizing powered parachute flying obtained more subscribers than anyone else in the niche.

He continues to work on improving training in the sport by working on a second edition to his book (

FAA has two ways to correct that, Roy noted. "One is to create commercial ratings for powered parachute and weight-shift-control (trike) pilots," he claririfed. "Another is to allow powered parachute and weight shift control pilots rated at the private level to perform commercial work in special light sport aircraft. In either case, the FAA would also have to allow powered parachutes and weight shift control aircraft as special light sport to be used for commercial work."

Powered parachutes have a lot of potential uses for agriculture, construction, and surveying, Roy observed. "Hopefully the FAA will allow the industry to tap some of that potential with the final Mosaic rule."

FAA has two ways to correct that, Roy noted. "One is to create commercial ratings for powered parachute and weight-shift-control (trike) pilots," he claririfed. "Another is to allow powered parachute and weight shift control pilots rated at the private level to perform commercial work in special light sport aircraft. In either case, the FAA would also have to allow powered parachutes and weight shift control aircraft as special light sport to be used for commercial work."

Powered parachutes have a lot of potential uses for agriculture, construction, and surveying, Roy observed. "Hopefully the FAA will allow the industry to tap some of that potential with the final Mosaic rule."

If you are looking to buy, getting a current owner to part with their pride and joy could be challenging. The

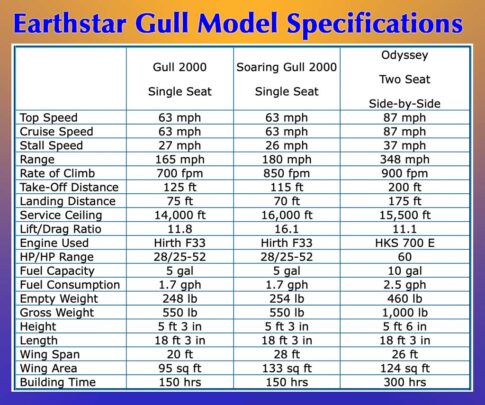

If you are looking to buy, getting a current owner to part with their pride and joy could be challenging. The  Later came Odyssey, a side-by-side, staggered-seating two seater. It only had a 26 foot wingspan. Most light aircraft in the space use 30-36 foot wingspans on aircraft that did not carry any more payload. Consequently, I viewed Thunder Gull's wing design to be "hard working."

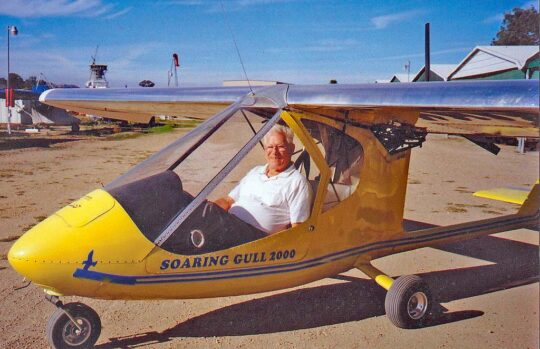

Later still came Soaring Gull with what looked to be a long wing, 28 feet, still shorter than most other comparable aircraft. This gave Soaring Gull a solid 16:1 glide according to Earthstar, meaning any experienced soaring pilot could easily keep Soaring Gull aloft for a long time with the engine shut down. This fact later lead to electric power, which I'll touch on below.

Later came Odyssey, a side-by-side, staggered-seating two seater. It only had a 26 foot wingspan. Most light aircraft in the space use 30-36 foot wingspans on aircraft that did not carry any more payload. Consequently, I viewed Thunder Gull's wing design to be "hard working."

Later still came Soaring Gull with what looked to be a long wing, 28 feet, still shorter than most other comparable aircraft. This gave Soaring Gull a solid 16:1 glide according to Earthstar, meaning any experienced soaring pilot could easily keep Soaring Gull aloft for a long time with the engine shut down. This fact later lead to electric power, which I'll touch on below.

While giants like Boeing and Airbus spend billions on electric propulsion concepts, electric airplane development of affordable aircraft is often done on tiny budgets by entrepreneurs like Mark.

This is also a fast-changing field, perhaps explaining why finding an electric-powered Earthstar Gull will be especially difficult. Nonetheless, the efficiency of Mark Beierle's Gull design combined the high torque of an electric motor with a low airframe weight to make a highly-workable electric propulsion design.

While giants like Boeing and Airbus spend billions on electric propulsion concepts, electric airplane development of affordable aircraft is often done on tiny budgets by entrepreneurs like Mark.

This is also a fast-changing field, perhaps explaining why finding an electric-powered Earthstar Gull will be especially difficult. Nonetheless, the efficiency of Mark Beierle's Gull design combined the high torque of an electric motor with a low airframe weight to make a highly-workable electric propulsion design.

"The new and very modern Polini 303DS engine is gaining my trust. It has worked flawlessly. But with the glide ratio of the Merlin Lite and the low landing speed and big tires an off-airport landing is not likely to be an issue. Still, I like to have confidence in my power system and I am beginning to think that this engine is a lot more reliable than our 1980s engines.

"Our new electric power system will be perfect for this aircraft. Our target of one-hour flight endurance is likely to be exceeded and with only a 9 Kwh battery pack. The electric-powered Merlin Lite will really make an excellent motor-glider. No re-start issues.

"The new and very modern Polini 303DS engine is gaining my trust. It has worked flawlessly. But with the glide ratio of the Merlin Lite and the low landing speed and big tires an off-airport landing is not likely to be an issue. Still, I like to have confidence in my power system and I am beginning to think that this engine is a lot more reliable than our 1980s engines.

"Our new electric power system will be perfect for this aircraft. Our target of one-hour flight endurance is likely to be exceeded and with only a 9 Kwh battery pack. The electric-powered Merlin Lite will really make an excellent motor-glider. No re-start issues.

"Soon we will be flying the Merlin Lite on our 750 straight floats. Expect to see some really nice video of those flights. Flying any seaplane is about the best flying there is. Imagine flying an electric-powered seaplane! Quiet, slow, smooth, perfect at low altitudes.

"For those wanting a bit more speed we will still offer the original wings. That version is also a hoot to fly.

"Soon we will be flying the Merlin Lite on our 750 straight floats. Expect to see some really nice video of those flights. Flying any seaplane is about the best flying there is. Imagine flying an electric-powered seaplane! Quiet, slow, smooth, perfect at low altitudes.

"For those wanting a bit more speed we will still offer the original wings. That version is also a hoot to fly.

"Part 103 ultralights must meet quite strict weight and speed requirements. 27 mile per hour stall, 63 mile per hour top speed, and 254 pounds empty, or 278 pounds empty with a whole airframe rescue parachute. Of course, every manufacturer of ultralights offers a model that meets those parameters. But no one buys it. Every customer adds some options. Of course, the Merlin Lite complies with Part 103. We have proven it. Just choose your options to meet your flying preferences. Call me for advice. We will make the perfect aircraft custom for you."

That's what Chip thinks. What do you think?

"Part 103 ultralights must meet quite strict weight and speed requirements. 27 mile per hour stall, 63 mile per hour top speed, and 254 pounds empty, or 278 pounds empty with a whole airframe rescue parachute. Of course, every manufacturer of ultralights offers a model that meets those parameters. But no one buys it. Every customer adds some options. Of course, the Merlin Lite complies with Part 103. We have proven it. Just choose your options to meet your flying preferences. Call me for advice. We will make the perfect aircraft custom for you."

That's what Chip thinks. What do you think?

A ready-to-fly Merlin Lite landplane lists for a confirmed price of $34,000 in fall of 2023. By itself, for an all-metal aircraft of these features, that seems an exceptional value.

For the long wings, add $5,000 so now $39,000 RTF. For assembled, painted floats with all installation hardware for Merlin Lite, add $7,600.

Now we're at $46,600, so even with freight and other delivery expenses you should have a full aircraft as seen in nearby images for less than $50,000. As we head into 2024, I'd call that a bargain for a Part 103 floatplane motorglider.

A ready-to-fly Merlin Lite landplane lists for a confirmed price of $34,000 in fall of 2023. By itself, for an all-metal aircraft of these features, that seems an exceptional value.

For the long wings, add $5,000 so now $39,000 RTF. For assembled, painted floats with all installation hardware for Merlin Lite, add $7,600.

Now we're at $46,600, so even with freight and other delivery expenses you should have a full aircraft as seen in nearby images for less than $50,000. As we head into 2024, I'd call that a bargain for a Part 103 floatplane motorglider.

Deon is not the first to go after the Whisper prize in America but he is taking a different approach. Here's the update on Whisper, which looks remarkably like an RV made out of composite.

Deon is not the first to go after the Whisper prize in America but he is taking a different approach. Here's the update on Whisper, which looks remarkably like an RV made out of composite.

As spring arrives, look for Deon and Whisper at

As spring arrives, look for Deon and Whisper at

Designed for up to 200 horsepower Whisper can perform well on 160-180 horsepower (perhaps making it a kit-builder candidate for Rotax's new 916iS at 160 horsepower). Like many RVs, Whisper Aircraft currently recommends a Lycoming 180 horsepower engine.

The fuselage, molded in upper and lower sections, is furnished as a fully joined assembly, complete with vertical fin, rather than as two halves requiring gluing together. Working with composites requires different skills than metal or joining tubes together by bolts or welding but can be finished quicker than most RVs are done, claims the factory.

Designed for up to 200 horsepower Whisper can perform well on 160-180 horsepower (perhaps making it a kit-builder candidate for Rotax's new 916iS at 160 horsepower). Like many RVs, Whisper Aircraft currently recommends a Lycoming 180 horsepower engine.

The fuselage, molded in upper and lower sections, is furnished as a fully joined assembly, complete with vertical fin, rather than as two halves requiring gluing together. Working with composites requires different skills than metal or joining tubes together by bolts or welding but can be finished quicker than most RVs are done, claims the factory.

According to Whisper Aircraft, “An X350 kit can be completed in about 500 hours depending on your current skill set.” All structural components and large surfaces are shipped completed. Composite parts have a base coat already sprayed to assure product quality.

“The kit ships with 90%-built wings, horizontal stabilizer, rudder, flaps, ailerons, elevators, and fuselage. Within a short time your aircraft will be ready for motor installations,” said Whisper Aircraft. While the big parts apparently come substantially done, the details of engine installation, wiring and plumbing plus finishing the exterior and interior easily assure Whisper X360 Gen II can quality as a U.S. Experimental Amateur Built aircraft.

According to Whisper Aircraft, “An X350 kit can be completed in about 500 hours depending on your current skill set.” All structural components and large surfaces are shipped completed. Composite parts have a base coat already sprayed to assure product quality.

“The kit ships with 90%-built wings, horizontal stabilizer, rudder, flaps, ailerons, elevators, and fuselage. Within a short time your aircraft will be ready for motor installations,” said Whisper Aircraft. While the big parts apparently come substantially done, the details of engine installation, wiring and plumbing plus finishing the exterior and interior easily assure Whisper X360 Gen II can quality as a U.S. Experimental Amateur Built aircraft.

A specialty flight training outfit called

A specialty flight training outfit called