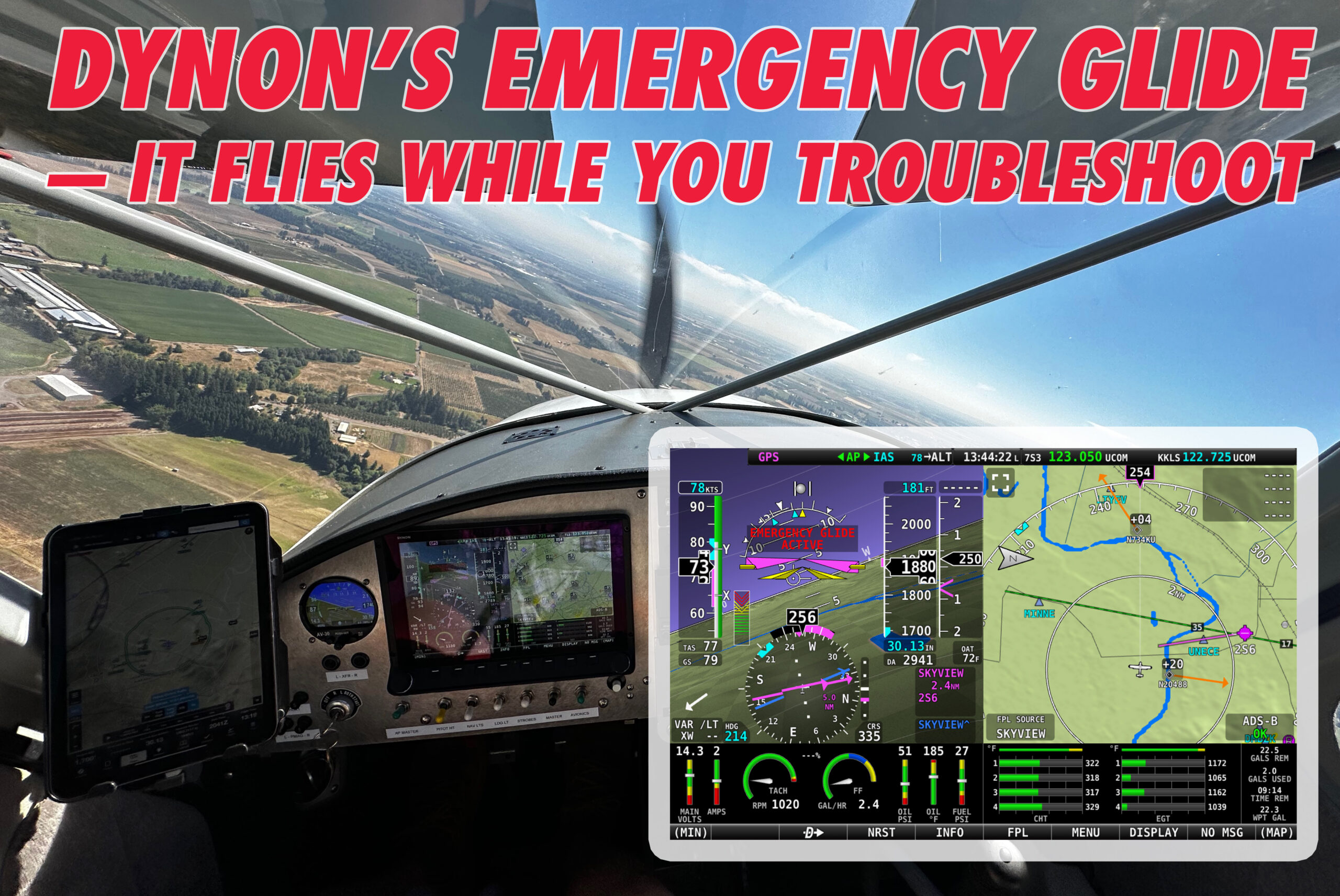

ByDanJohnson.com content integrates for enhanced light sport and recreational flying coverage. Firecrown Media Inc., a leading media company in the aviation sector and owner of highly respected resources ByDanJohnson.com and Plane & Pilot, announced a strategic integration that will see ByDanJohnson.com merge its content and focus directly into Plane & Pilot’s digital platform. ByDanJohnson.com has long been recognized as the definitive online resource for light sport and recreational aircraft, providing in-depth coverage and advocacy for the sector. This exciting development will create a dedicated and distinct new section on PlaneandPilotMag.com titled “Affordable Aviation.” This move is designed to consolidate Firecrown’s digital presence, providing readers with a more streamlined and comprehensive experience, while continuing to champion the growth and accessibility of light sport and affordable aircraft. Dan Johnson, the namesake founder of ByDanJohnson.com, will continue his invaluable contributions to aviation journalism. He is a regular and prominent contributor to Plane & Pilot magazine and, soon, the new “Affordable Aviation” section online, bringing his unparalleled expertise and insights to an even wider audience.

U.S. government policies swing and sway the world in remarkable ways. That's a whole story in itself, but the way aircraft suppliers respond to the situation they are facing can be instructive.

To be clear, AeroJones Aviation is not reacting to tariff changes. This company, headquartered in U.S.-friendly Taiwan, has been working toward entering the American market for years. For more than a decade, AeroJones has been the officially-licensed producer of Flight Design's CTLS and CTLSi for Asia-Pacific. They don't simply import and sell units built in Europe. They do 100% of the fabrication, assembly, and production test flights in the Asian theater. They've delivered more than 50 aircraft and have won multiple CAAC airworthiness approvals.

U.S. government policies swing and sway the world in remarkable ways. That's a whole story in itself, but the way aircraft suppliers respond to the situation they are facing can be instructive.

To be clear, AeroJones Aviation is not reacting to tariff changes. This company, headquartered in U.S.-friendly Taiwan, has been working toward entering the American market for years. For more than a decade, AeroJones has been the officially-licensed producer of Flight Design's CTLS and CTLSi for Asia-Pacific. They don't simply import and sell units built in Europe. They do 100% of the fabrication, assembly, and production test flights in the Asian theater. They've delivered more than 50 aircraft and have won multiple CAAC airworthiness approvals.

A video to follow soon features

A video to follow soon features  What does AeroJones USA offer of interest? Below I'll describe the sophisticated aircraft that is AJ Sport but one leading quality is a more affordable price — and yes, I know how loaded that word "affordable" is; bear with me.

What does AeroJones USA offer of interest? Below I'll describe the sophisticated aircraft that is AJ Sport but one leading quality is a more affordable price — and yes, I know how loaded that word "affordable" is; bear with me.

Using government reports, the U.S. inflation rate has averaged 4.89% annually for the last 20-some years, making $60,000 then similar to $180,000 today. No doubt; a dollar doesn't buy what it used to. Some readers may find the 2025 price beyond reach, yet I see AJ Sport at $179,000 as a solid value closely approximating our earlier expectations.

Come to EAA AirVenture Oshkosh 2025 and see AJ Sport's production quality for yourself. Nearly all who examine it will come away impressed.

Using government reports, the U.S. inflation rate has averaged 4.89% annually for the last 20-some years, making $60,000 then similar to $180,000 today. No doubt; a dollar doesn't buy what it used to. Some readers may find the 2025 price beyond reach, yet I see AJ Sport at $179,000 as a solid value closely approximating our earlier expectations.

Come to EAA AirVenture Oshkosh 2025 and see AJ Sport's production quality for yourself. Nearly all who examine it will come away impressed.

The 2025 AeroJones USA AJ Sport has most of the features and equipment even a seasoned aircraft buyer might seek.

The 2025 AeroJones USA AJ Sport has most of the features and equipment even a seasoned aircraft buyer might seek.

"We have a completely redesigned fuel system to reduce vapor lock, a new engine cowling for enhanced cooling, a larger wingspan with curved winglets for better slower speed handling, and VGs for lower stall speed and softer controlled landings," stated Abid. Visually, AJ Sport looks very familiar but under its smooth carbon fiber skin, these notable changes were desired but also required to meet new, ever-better ASTM standards, which all LSA must prove to gain FAA acceptance for sale in America.

"We have a completely redesigned fuel system to reduce vapor lock, a new engine cowling for enhanced cooling, a larger wingspan with curved winglets for better slower speed handling, and VGs for lower stall speed and softer controlled landings," stated Abid. Visually, AJ Sport looks very familiar but under its smooth carbon fiber skin, these notable changes were desired but also required to meet new, ever-better ASTM standards, which all LSA must prove to gain FAA acceptance for sale in America. "You can cruise easily at 110 knots at 75% power," observed Abid, "or opt for maximum fuel economy at 100 knots sipping less than four gallons an hour. A 34-gallon fuel capacity provides the freedom to fly more than 825 nautical miles non-stop and still have a 30-minute reserve." AJ Sport's fuel is safely stored in the wings, away from the fuselage, providing added protection for you and a passenger.

"You can cruise easily at 110 knots at 75% power," observed Abid, "or opt for maximum fuel economy at 100 knots sipping less than four gallons an hour. A 34-gallon fuel capacity provides the freedom to fly more than 825 nautical miles non-stop and still have a 30-minute reserve." AJ Sport's fuel is safely stored in the wings, away from the fuselage, providing added protection for you and a passenger.

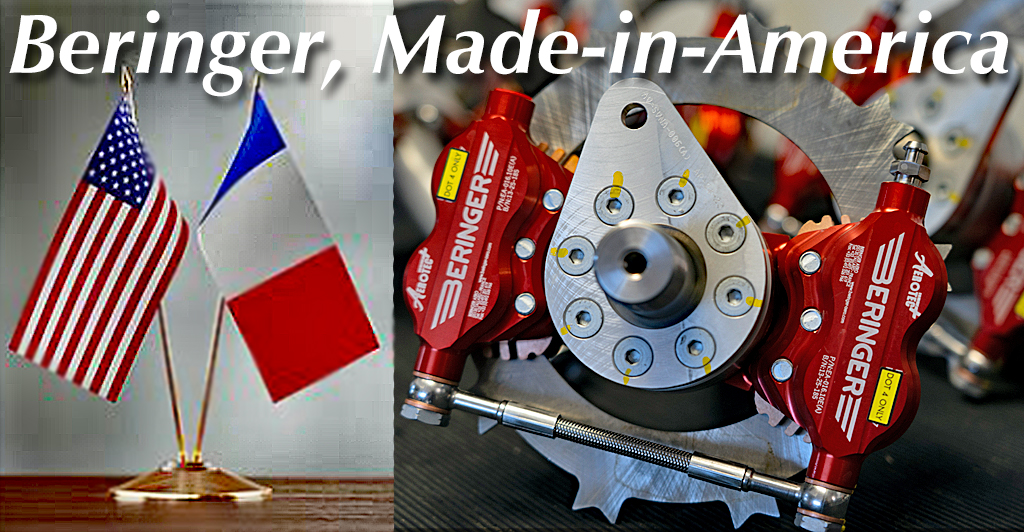

Claire also noted 2025 marks her company's 40th anniversary. "We are profoundly grateful to our customers, partners, and friends who have supported us throughout these decades. Our commitment to innovation and quality in the aircraft wheel and brake industry remains unwavering."

Claire also noted 2025 marks her company's 40th anniversary. "We are profoundly grateful to our customers, partners, and friends who have supported us throughout these decades. Our commitment to innovation and quality in the aircraft wheel and brake industry remains unwavering."

The Greenville, SC facility will enable Beringer to dramatically improve their response times and provide in-country service capabilities. "By bringing production closer to our U.S. customers, we're not just expanding our manufacturing footprint but also investing directly in the local community," Claire stated. She and COO Trevor Burnette expressed keen enthusiasm about their strategic move.

The Greenville, SC facility will enable Beringer to dramatically improve their response times and provide in-country service capabilities. "By bringing production closer to our U.S. customers, we're not just expanding our manufacturing footprint but also investing directly in the local community," Claire stated. She and COO Trevor Burnette expressed keen enthusiasm about their strategic move. Beringer's current product lineup includes an extensive range of visual documentation, featuring detailed assembly pictures and comprehensive views of their new brake pad technologies.

Beringer's current product lineup includes an extensive range of visual documentation, featuring detailed assembly pictures and comprehensive views of their new brake pad technologies. Our recruitment efforts reflect our commitment to building a team that shares our vision of innovation, quality, and customer service. We believe that the right talent can help us continue to push the boundaries of what's possible in aircraft wheel and brake technology.

Our recruitment efforts reflect our commitment to building a team that shares our vision of innovation, quality, and customer service. We believe that the right talent can help us continue to push the boundaries of what's possible in aircraft wheel and brake technology. See a portion of Beringer's extensive product line and hear from CEO Claire Beringer as she talks about their distinctive products for light aircraft.

https://youtu.be/LjRSrHlQXPY?si=AtCCnj-7KvNGPh3I

See a portion of Beringer's extensive product line and hear from CEO Claire Beringer as she talks about their distinctive products for light aircraft.

https://youtu.be/LjRSrHlQXPY?si=AtCCnj-7KvNGPh3I

Welcome to Saberwing, an affordable composite kit from

Welcome to Saberwing, an affordable composite kit from  Introduced ten years ago at Sun ’n Fun 2015, this low-wing EAB is "designed to address challenges in the kit aircraft market, emphasizing a simplicity to the kit's components with fast assembly (500-1,000 hours)." For comparison, RVs often take more than 3,000 hours.

Construction is a composite-foam sandwich with wood wing spars and ribs. Saberwing was designed with a low parts count to simplify assembly. Bill's elegantly simple wing is composed of two skins, six ribs, and a spar. The kit can be configured with tricycle or taildragger landing gear with optional wheel pants as shown in the nearby images.

Introduced ten years ago at Sun ’n Fun 2015, this low-wing EAB is "designed to address challenges in the kit aircraft market, emphasizing a simplicity to the kit's components with fast assembly (500-1,000 hours)." For comparison, RVs often take more than 3,000 hours.

Construction is a composite-foam sandwich with wood wing spars and ribs. Saberwing was designed with a low parts count to simplify assembly. Bill's elegantly simple wing is composed of two skins, six ribs, and a spar. The kit can be configured with tricycle or taildragger landing gear with optional wheel pants as shown in the nearby images.

At 43-inches wide (four inches wider than a Cessna 172), Saberwing has fixed seats but adjustable rudder pedals. It has been shown to accommodate pilots up to 6 foot 6 with ample legroom and headroom.

In the light aircraft space, few companies attempt both airframe and engine. In so doing, Saberwing joins Sonex and Jabiru who offer both. Saberwing's standard engine is a 100 horsepower Spyder Corvair conversion of the air-cooled, flat-six automotive engine. A turbocharged version, as shown nearby, outputs 120 horsepower and allows higher elevation operation.

Saberwing kit contains airframe structural components, controls and linkages, composite parts (cowling, canopy), motor mount, fuel tank hardware, pumps, pedal assembly, wheels, brakes, and nose gear or tailwheel kit.

At 43-inches wide (four inches wider than a Cessna 172), Saberwing has fixed seats but adjustable rudder pedals. It has been shown to accommodate pilots up to 6 foot 6 with ample legroom and headroom.

In the light aircraft space, few companies attempt both airframe and engine. In so doing, Saberwing joins Sonex and Jabiru who offer both. Saberwing's standard engine is a 100 horsepower Spyder Corvair conversion of the air-cooled, flat-six automotive engine. A turbocharged version, as shown nearby, outputs 120 horsepower and allows higher elevation operation.

Saberwing kit contains airframe structural components, controls and linkages, composite parts (cowling, canopy), motor mount, fuel tank hardware, pumps, pedal assembly, wheels, brakes, and nose gear or tailwheel kit.

Bill Clapp likes to mention Maximum Visual Progress for his kit. The design can sit on its wheels in a week of work and builders can sit in the fuselage within a few more days. Bill believes this helps keep motivation high and encourages first-time builders.

Anything you build will require maintenance and Saberwing has one great design element to ease a mechanic's effort. Not only does the cowl fully uncover the engine but just aft a removable forward deck allows stand-up (not lay-on-your-back) access to all the avionics connections and control linkages in that area.

Bill Clapp likes to mention Maximum Visual Progress for his kit. The design can sit on its wheels in a week of work and builders can sit in the fuselage within a few more days. Bill believes this helps keep motivation high and encourages first-time builders.

Anything you build will require maintenance and Saberwing has one great design element to ease a mechanic's effort. Not only does the cowl fully uncover the engine but just aft a removable forward deck allows stand-up (not lay-on-your-back) access to all the avionics connections and control linkages in that area.

At Sun 'n Fun 2025, Bill quoted a base Saberwing kit price at $35,000. When I asked about completed in-the-air cost, Bill said a basic VFR model with his 100 horsepower Spyder could get airborne for $55,000, of course not including the builder's time. In 2025, this qualifies as a bargain, a genuine "affordable" aircraft selling for the price of a new pickup truck.

At Sun 'n Fun 2025, Bill quoted a base Saberwing kit price at $35,000. When I asked about completed in-the-air cost, Bill said a basic VFR model with his 100 horsepower Spyder could get airborne for $55,000, of course not including the builder's time. In 2025, this qualifies as a bargain, a genuine "affordable" aircraft selling for the price of a new pickup truck.

Helping contain the airborne price, Azalea's Spyder Corvair engine conversion with some specialized elements sells for $10,500 (100 hp) or $12,995 for the turbocharged version (120 hp),

Multiple kits have been sold, with eight aircraft signed off and flying as of this year's Sun 'n Fun, Bill confirmed.

Helping contain the airborne price, Azalea's Spyder Corvair engine conversion with some specialized elements sells for $10,500 (100 hp) or $12,995 for the turbocharged version (120 hp),

Multiple kits have been sold, with eight aircraft signed off and flying as of this year's Sun 'n Fun, Bill confirmed.

A fatal 2018 crash brought safety questions although an NTSB investigation did not highlight design flaws.

While some have spoken about two fatal accidents (see below), the Saberwing and Spyder have advocates as presented via comments to the video below.

A fatal 2018 crash brought safety questions although an NTSB investigation did not highlight design flaws.

While some have spoken about two fatal accidents (see below), the Saberwing and Spyder have advocates as presented via comments to the video below.

After one video commenter alleged problems with aircraft and engine, another reader responded. Both are public comments openly offered to the video (and you can see them for yourself). I chose to present the following given the qualifications of the responder, his role investigating accidents, and the fact that he had conversations with both pilots who lost their lives. I present this not to stir controversy but to add depth to these most unfortunate losses. I only edited to split paragraphs to make reading easier. The commenter's words are unaltered.

YouTube commenter @boldasthelion6496 replied, "[If] you knew the two pilots who were killed you would know the back stories. NEITHER fatal mishap is attributable to a problem or defect in the Saberwing airframe or the power plants involved.

"The first fatality was due to a pilot attempting aerobatics he was not trained for. He had zero experience in this realm. That lack of experience cost him his life.

After one video commenter alleged problems with aircraft and engine, another reader responded. Both are public comments openly offered to the video (and you can see them for yourself). I chose to present the following given the qualifications of the responder, his role investigating accidents, and the fact that he had conversations with both pilots who lost their lives. I present this not to stir controversy but to add depth to these most unfortunate losses. I only edited to split paragraphs to make reading easier. The commenter's words are unaltered.

YouTube commenter @boldasthelion6496 replied, "[If] you knew the two pilots who were killed you would know the back stories. NEITHER fatal mishap is attributable to a problem or defect in the Saberwing airframe or the power plants involved.

"The first fatality was due to a pilot attempting aerobatics he was not trained for. He had zero experience in this realm. That lack of experience cost him his life.

"The NTSB report will not come out on the second mishap (the one involving the aircraft featured in the video below) for some time, but it has the hallmarks of a pilot putting himself in a bad situation by pushing his physical limits. He did this despite having discussions just prior to flight cautioning him of the risks involved in pushing too hard.

"For reasons unknown to anyone but the pilot, he pressed ahead anyway. I did not 'know' either of these pilots other than to have talked to them each once or twice on the phone. In both cases, they exceeded their limits, NOT the limits of the mishap aircraft.

"Aviation is not like driving a car. It is not forgiving. It is not a game. One can find himself in a bad situation with no way out quickly. Sometimes the best solution is not to fly.

"The NTSB report will not come out on the second mishap (the one involving the aircraft featured in the video below) for some time, but it has the hallmarks of a pilot putting himself in a bad situation by pushing his physical limits. He did this despite having discussions just prior to flight cautioning him of the risks involved in pushing too hard.

"For reasons unknown to anyone but the pilot, he pressed ahead anyway. I did not 'know' either of these pilots other than to have talked to them each once or twice on the phone. In both cases, they exceeded their limits, NOT the limits of the mishap aircraft.

"Aviation is not like driving a car. It is not forgiving. It is not a game. One can find himself in a bad situation with no way out quickly. Sometimes the best solution is not to fly.

"I am an experienced Aviation Mishap Investigator. It was my job to piece aircraft together after they crashed and determine the causes.

"With this background, I choose to fly the Saberwing myself. The aircraft is safe. The Corvair engine is proven. I minimize risk factors every time I fly because I have grandchildren and wish to still be around to enjoy my great grandchildren.

"I am an experienced Aviation Mishap Investigator. It was my job to piece aircraft together after they crashed and determine the causes.

"With this background, I choose to fly the Saberwing myself. The aircraft is safe. The Corvair engine is proven. I minimize risk factors every time I fly because I have grandchildren and wish to still be around to enjoy my great grandchildren.

Giants like GAMA, the General Aviation Manufacturers Association and small organizations like

Giants like GAMA, the General Aviation Manufacturers Association and small organizations like

EAA's Pelton offered several insights, including this comment, that will thrill many pilots who have followed Mosaic’s development, “This [new rule] will encompass airplanes like the Cessna 172 and Cessna 182.”

AOPA's Pleasance was even more plainspoken, “Nothing [about Mosaic] has slowed down or stopped. It’s still a priority for FAA." He observed recent conversations indicate that FAA considers Mosaic “a win” — then adding, “And they [FAA] need a win right now.”

EAA's Pelton offered several insights, including this comment, that will thrill many pilots who have followed Mosaic’s development, “This [new rule] will encompass airplanes like the Cessna 172 and Cessna 182.”

AOPA's Pleasance was even more plainspoken, “Nothing [about Mosaic] has slowed down or stopped. It’s still a priority for FAA." He observed recent conversations indicate that FAA considers Mosaic “a win” — then adding, “And they [FAA] need a win right now.”

I wrote about BRM hitting

I wrote about BRM hitting  BRM AERO MODEL LIST

BRM AERO MODEL LIST "Our versatile aircraft offers multiple capabilities that cater to different flying needs," BRM Aero elaborated. "During the certification process for the tug model, we extensively tested the aircraft in challenging mountain conditions, where it particularly shone in glider towing operations, easily handling gliders up to 850 kilograms (about 1,875 pounds)." Towing more than it weighs is a notable point.

"BRM Aero is a family company primarily focusing on individual custom-built airplanes," explained founder (and father) Milan Bříštěla. "[We are] able to carry out all kinds of modifications according to customer requirements. Each customer can therefore get a unique airplane that best suits their needs."

"Our versatile aircraft offers multiple capabilities that cater to different flying needs," BRM Aero elaborated. "During the certification process for the tug model, we extensively tested the aircraft in challenging mountain conditions, where it particularly shone in glider towing operations, easily handling gliders up to 850 kilograms (about 1,875 pounds)." Towing more than it weighs is a notable point.

"BRM Aero is a family company primarily focusing on individual custom-built airplanes," explained founder (and father) Milan Bříštěla. "[We are] able to carry out all kinds of modifications according to customer requirements. Each customer can therefore get a unique airplane that best suits their needs."

The father and son duo at the helm of BRM Aero have obviously been mighty busy building a company from scratch and rising to the upper ranks in a remarkably short time. Milan founded BRM AERO s.r.o. in 2009, just 15 years ago. His son Martin was in at the start and has now risen to become CEO of the company. Today, the business employs 135 people.

The father and son duo at the helm of BRM Aero have obviously been mighty busy building a company from scratch and rising to the upper ranks in a remarkably short time. Milan founded BRM AERO s.r.o. in 2009, just 15 years ago. His son Martin was in at the start and has now risen to become CEO of the company. Today, the business employs 135 people.

In addition to supporting the popular and potent 916iS powerplant, BRM Aero has another 160-horsepower trick up its sleeve, at least for those with a thicker wallet.

'We are proud to announce [that] we successfully achieved the first 300 flight hours with a new powerplant from Turbotech. Our Bristell Turbine will be available as an Ultralight (UL) with a turbine engine in Europe, or as a Mosaic plane in the USA. Key features include an exceptionally smooth sound, no vibration, and turbine power characteristics of up to 160 horsepower," stated Martin.

In addition to supporting the popular and potent 916iS powerplant, BRM Aero has another 160-horsepower trick up its sleeve, at least for those with a thicker wallet.

'We are proud to announce [that] we successfully achieved the first 300 flight hours with a new powerplant from Turbotech. Our Bristell Turbine will be available as an Ultralight (UL) with a turbine engine in Europe, or as a Mosaic plane in the USA. Key features include an exceptionally smooth sound, no vibration, and turbine power characteristics of up to 160 horsepower," stated Martin.

Read more

Read more I can only wonder what BRM Aero might achieve in 2025 and beyond but I'm willing to bet their production and delivery numbers keep rising.

I can only wonder what BRM Aero might achieve in 2025 and beyond but I'm willing to bet their production and delivery numbers keep rising.

Currently, new rules are proposed, then discussed by government and the public. Afterward, FAA huddles and writes the proposed rule. When done, a notice of proposed rulemaking is offered for public comment. After the comment period closes, the federal agency goes quiet to revise the rule without outside interference. After the rule is published, the public can comment no more.

Currently, new rules are proposed, then discussed by government and the public. Afterward, FAA huddles and writes the proposed rule. When done, a notice of proposed rulemaking is offered for public comment. After the comment period closes, the federal agency goes quiet to revise the rule without outside interference. After the rule is published, the public can comment no more.

While Trump's regulatory changes may be worthy, any change to the way Washington works means regulations take longer. Since pilots are somewhat forced to wait for regulation to emerge before they can buy exciting new airplanes, any alteration that permits pilots to see the finalized rule before it is released seems laudable — though this necessarily extends the time needed.

In short, the odds of further delay in Mosaic's release appears probable. Stay alert!

Roy's 11-minute video below clarifies much more on this Regulatory Freeze Pending Review…

While Trump's regulatory changes may be worthy, any change to the way Washington works means regulations take longer. Since pilots are somewhat forced to wait for regulation to emerge before they can buy exciting new airplanes, any alteration that permits pilots to see the finalized rule before it is released seems laudable — though this necessarily extends the time needed.

In short, the odds of further delay in Mosaic's release appears probable. Stay alert!

Roy's 11-minute video below clarifies much more on this Regulatory Freeze Pending Review…

Jaro's work included the

Jaro's work included the  As North American importer, Chris Horsten, details in the video below, Shark 600 uses 3D-printed parts in non-critical, non-structural areas. The factory makes good use of this technology to facilitate and streamline production in areas that would be cost-prohibitive or time-consuming. "Examples of visible parts are the stick and throttle," said Shark Aero. Chris noted other uses like gear-door latches.

Chris runs

As North American importer, Chris Horsten, details in the video below, Shark 600 uses 3D-printed parts in non-critical, non-structural areas. The factory makes good use of this technology to facilitate and streamline production in areas that would be cost-prohibitive or time-consuming. "Examples of visible parts are the stick and throttle," said Shark Aero. Chris noted other uses like gear-door latches.

Chris runs  In my experience Shark handled beautifully. Roll control was moderate, not touchy. Elevator and rudder controls felt solid, befitting an aircraft of this size and construction. In turns, Shark held bank and altitude easily. Being tandem, the pilot always sits at the lateral center of gravity so the airplane quickly begins to feel like a part of you. We did nothing very radical but 720° steep turns at 45-60° bank revealed an aircraft that grips the air firmly. Shark always felt predictable.

As Chris notes in the video, stall is very slow on Shark. It looks like it is a speedster — and it does well — but the slow speed capabilities surprised a number of experienced pilots who examined the aircraft while I was setting up to interview Chris. A flaps-extended stall well below 40 knots is much lower than most expected.

In my experience Shark handled beautifully. Roll control was moderate, not touchy. Elevator and rudder controls felt solid, befitting an aircraft of this size and construction. In turns, Shark held bank and altitude easily. Being tandem, the pilot always sits at the lateral center of gravity so the airplane quickly begins to feel like a part of you. We did nothing very radical but 720° steep turns at 45-60° bank revealed an aircraft that grips the air firmly. Shark always felt predictable.

As Chris notes in the video, stall is very slow on Shark. It looks like it is a speedster — and it does well — but the slow speed capabilities surprised a number of experienced pilots who examined the aircraft while I was setting up to interview Chris. A flaps-extended stall well below 40 knots is much lower than most expected.

In flight we dawdled along at 50 knots with relative ease, especially knowing the stall was still 10-15 knots slower. Stalls tend not to drop a wing depending somewhat on how you enter the condition. Controls become softer, of course, but remained authoritative.

That translates to an aircraft that can accommodate fairly short runways. Takeoff is typical between 400-600 feet, said Chris. We landed on two long, confortable runways but we didn't use much of either. Climbout was brisk, 800-1,000 feet per minute at sea level with two aboard and three quarter tanks. Shark's deck angle remained shallow. This gives better forward visibility but some pilots may tend to raise the nose depending on what they flew earlier.

In flight we dawdled along at 50 knots with relative ease, especially knowing the stall was still 10-15 knots slower. Stalls tend not to drop a wing depending somewhat on how you enter the condition. Controls become softer, of course, but remained authoritative.

That translates to an aircraft that can accommodate fairly short runways. Takeoff is typical between 400-600 feet, said Chris. We landed on two long, confortable runways but we didn't use much of either. Climbout was brisk, 800-1,000 feet per minute at sea level with two aboard and three quarter tanks. Shark's deck angle remained shallow. This gives better forward visibility but some pilots may tend to raise the nose depending on what they flew earlier.

The price of the Shark aircraft "reflects the cost of thousands of precision-engineered parts, an all-carbon fibre structure with a Kevlar cage, and approximately 4,000 hours of skilled craftsmanship," noted the factory. They've delivered more than 100 aircraft, mostly around Europe.

The price of the Shark aircraft "reflects the cost of thousands of precision-engineered parts, an all-carbon fibre structure with a Kevlar cage, and approximately 4,000 hours of skilled craftsmanship," noted the factory. They've delivered more than 100 aircraft, mostly around Europe.

One of the most remarkable achievements came during Mack's journey. In the longest flight of the missions, Shark carried him non-stop for 10 hours from Kushiro, Japan, to Casco Cove, USA, without any refueling or stopovers. This flight also set a record for the longest distance flown over water.

In 2015, a new FAI world speed record was set by Eric de Barbarin-Barbarini, who clocked in at 303 kilometers per hour (163.6 knots). This record was set with a Rotax 912 ULS 100-horsepower naturally-aspirated engine, and without some of the more recent aerodynamic refinements which have since been incorporated into the airframe. —Shark Aero

One of the most remarkable achievements came during Mack's journey. In the longest flight of the missions, Shark carried him non-stop for 10 hours from Kushiro, Japan, to Casco Cove, USA, without any refueling or stopovers. This flight also set a record for the longest distance flown over water.

In 2015, a new FAI world speed record was set by Eric de Barbarin-Barbarini, who clocked in at 303 kilometers per hour (163.6 knots). This record was set with a Rotax 912 ULS 100-horsepower naturally-aspirated engine, and without some of the more recent aerodynamic refinements which have since been incorporated into the airframe. —Shark Aero

After proceedings were initiated with the responsible district court in Meiningen, Germany on Tuesday, December 3rd, 2024, the court appointed lawyer Marcello Di Stefano as provisional insolvency administrator.

According to an initial assessment, Di Stefano wrote, "After Flight Design general aviation GmbH filed for insolvency… [we see] good restructuring opportunities for one of the world market leaders in the construction of light aircraft." He added, "The company's order situation is good and the products have a very good reputation on the international market, and the outstanding debts are manageable."

After proceedings were initiated with the responsible district court in Meiningen, Germany on Tuesday, December 3rd, 2024, the court appointed lawyer Marcello Di Stefano as provisional insolvency administrator.

According to an initial assessment, Di Stefano wrote, "After Flight Design general aviation GmbH filed for insolvency… [we see] good restructuring opportunities for one of the world market leaders in the construction of light aircraft." He added, "The company's order situation is good and the products have a very good reputation on the international market, and the outstanding debts are manageable."

Short take

Short take Finally, we will learn the answers to many questions.

Of course, all this is expected as Trump takes office next month. With his push to eliminate 10 regulations for every new one, federal rule makers may exercise added caution so as not to get in trouble with the new boss — and I don't mean yet another new FAA administrator… I mean POTUS.

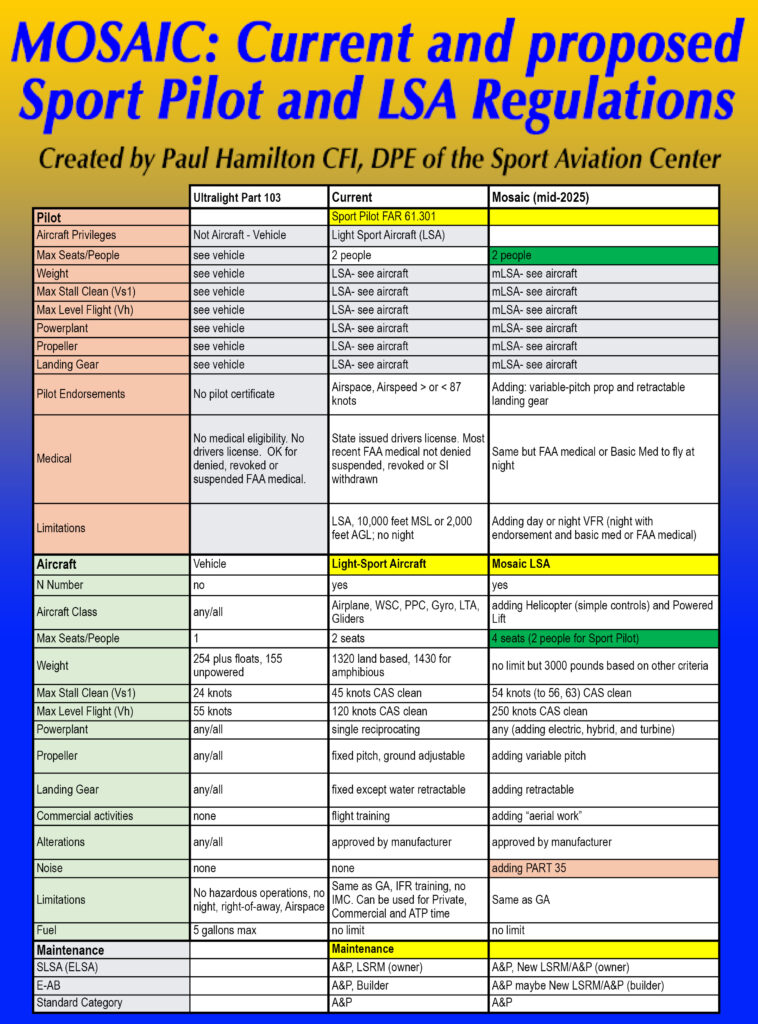

The following chart was assembled by longtime industry leader Paul Hamilton, proprietor of the

Finally, we will learn the answers to many questions.

Of course, all this is expected as Trump takes office next month. With his push to eliminate 10 regulations for every new one, federal rule makers may exercise added caution so as not to get in trouble with the new boss — and I don't mean yet another new FAA administrator… I mean POTUS.

The following chart was assembled by longtime industry leader Paul Hamilton, proprietor of the

You can build it or they can build it. A kit is available faster for obvious reasons. Fully factory-built models have a lengthy waiting list attesting to the loyalty the company has built over the decades. Presently, fully-assembled models are limited to LSA weights (1,320 pounds on wheels) but the airframe is already capable of 1,800 pounds. As soon as the flag drops on Mosaic, expect the manufacturer to make this available at the higher weight, again as Michele tells us in the interview.

I recommend you go right to the video. If you want even more detail, a second video goes into more depth about S-21 Outbound shortly after it was released. Below are a few additional observations…

You can build it or they can build it. A kit is available faster for obvious reasons. Fully factory-built models have a lengthy waiting list attesting to the loyalty the company has built over the decades. Presently, fully-assembled models are limited to LSA weights (1,320 pounds on wheels) but the airframe is already capable of 1,800 pounds. As soon as the flag drops on Mosaic, expect the manufacturer to make this available at the higher weight, again as Michele tells us in the interview.

I recommend you go right to the video. If you want even more detail, a second video goes into more depth about S-21 Outbound shortly after it was released. Below are a few additional observations…

A nosewheel Outbound is welcome because generations of pilots have received their instruction in a tricycle airplane and that's all most have ever flown. Many pilots have heard stories about ground loops causing damage and hurting pride so most stick to the familiar and more-forgiving tricycle undercarriage. Lighter aircraft are less challenging to handle on conventional (tailwheel) gear but for many, it's simply too big a leap. So, at Sun ‘n Fun 2019, the company brought Outbound in tricycle gear. Despite what many might have expected, the configuration looks good and was warmly received.

The nose wheel doesn’t affect handling or performance; “it flies the same as the tail dragger,” said Randy Schlitter when introducing the new configuration.

A nosewheel Outbound is welcome because generations of pilots have received their instruction in a tricycle airplane and that's all most have ever flown. Many pilots have heard stories about ground loops causing damage and hurting pride so most stick to the familiar and more-forgiving tricycle undercarriage. Lighter aircraft are less challenging to handle on conventional (tailwheel) gear but for many, it's simply too big a leap. So, at Sun ‘n Fun 2019, the company brought Outbound in tricycle gear. Despite what many might have expected, the configuration looks good and was warmly received.

The nose wheel doesn’t affect handling or performance; “it flies the same as the tail dragger,” said Randy Schlitter when introducing the new configuration.

Outbound can be powered by a 100 horsepower Rotax 912 that works brilliantly. Or, buyers can choose Continental's Titan X340 with 180 horsepower. Randy reports climb with the bigger engine is impressive (850 to 1,500 fpm) but fuel usage rises noticeably (from 5.5 to 7 gph). Takeoff is also fast with the big engine: just over 300 feet to leave the runway and just under 400 to land …in skilled hands, of course. However, interestingly the company quoted essentially the same launch and landing values for the Rotax 912, which is considerably lighter. A few of Titan's horses must be employed to lift its extra weight.

With the tricycle gear, you can have robust but smaller tires or you can opt for the tricycle version of bush gear. Doing so gives greater prop clearance as the video below identifies. Nearly all buyers are choosing the tundra option, Michele said. Outbound kits can go either way, taildragger or tri-gear. As Michele informs us, the main gear leg is the same on both aircraft. Company officials indicated it takes about four hours to swap out the hardware but the airframe is built to accommodate either configuration.

Outbound can be powered by a 100 horsepower Rotax 912 that works brilliantly. Or, buyers can choose Continental's Titan X340 with 180 horsepower. Randy reports climb with the bigger engine is impressive (850 to 1,500 fpm) but fuel usage rises noticeably (from 5.5 to 7 gph). Takeoff is also fast with the big engine: just over 300 feet to leave the runway and just under 400 to land …in skilled hands, of course. However, interestingly the company quoted essentially the same launch and landing values for the Rotax 912, which is considerably lighter. A few of Titan's horses must be employed to lift its extra weight.

With the tricycle gear, you can have robust but smaller tires or you can opt for the tricycle version of bush gear. Doing so gives greater prop clearance as the video below identifies. Nearly all buyers are choosing the tundra option, Michele said. Outbound kits can go either way, taildragger or tri-gear. As Michele informs us, the main gear leg is the same on both aircraft. Company officials indicated it takes about four hours to swap out the hardware but the airframe is built to accommodate either configuration.

When shopping for a light aircraft, it's hard to beat a homegrown American company. Have it your way and go enjoy one of the best flying (and most popular) aircraft in the LSA fleet.

When shopping for a light aircraft, it's hard to beat a homegrown American company. Have it your way and go enjoy one of the best flying (and most popular) aircraft in the LSA fleet.

Created by widely-known European designer Marek Ivanov beginning with 3D images at the beginning of 2021, Dingo rapidly took form and was put through test flights by Jan Jilek. The new creation entered production only two years later, in summer of 2023. Marek has lead development of several aircraft that show his great range. About Dingo he said, "My long-time dream was to build something like Hovey Whing Ding because I like it, but a little bigger so I can fly it." It's here in America now.

"No Americans had seen Dingo before," said Rick Bennett, one of two partners in the U.S. import business. "They flipped out over the design. We experienced strong attention."

Created by widely-known European designer Marek Ivanov beginning with 3D images at the beginning of 2021, Dingo rapidly took form and was put through test flights by Jan Jilek. The new creation entered production only two years later, in summer of 2023. Marek has lead development of several aircraft that show his great range. About Dingo he said, "My long-time dream was to build something like Hovey Whing Ding because I like it, but a little bigger so I can fly it." It's here in America now.

"No Americans had seen Dingo before," said Rick Bennett, one of two partners in the U.S. import business. "They flipped out over the design. We experienced strong attention."

Knowing they were launching a new design in the giant U.S, market,

Knowing they were launching a new design in the giant U.S, market,  Those who want to hold the cost to the minimum — "$25-27,000 is a reasonable estimate for most buyers," Rick estimated) — should plan on 300 hours of build time. However, no special jigs are needed as match-hole assembly assures accurate joining of components. Such sophisticated kits are now common in larger kit aircraft but not on a flying machine selling for such a modest price.

Bluff can legally deliver a fully-built aircraft because Dingo easily fits the parameters of Part 103 ultralights. As you see in the factory specs below, Future Vehicles can deliver an aircraft weighing only 210 pounds, a rather amazing 44 pounds under Part 103's limits. Americans fitting Dingo with a more powerful engine and high quality paint will weigh more but Rick and David both emphasized that it is easily possible to stay within Part 103 meaning no pilot medical is required nor are N-numbers.

Those who want to hold the cost to the minimum — "$25-27,000 is a reasonable estimate for most buyers," Rick estimated) — should plan on 300 hours of build time. However, no special jigs are needed as match-hole assembly assures accurate joining of components. Such sophisticated kits are now common in larger kit aircraft but not on a flying machine selling for such a modest price.

Bluff can legally deliver a fully-built aircraft because Dingo easily fits the parameters of Part 103 ultralights. As you see in the factory specs below, Future Vehicles can deliver an aircraft weighing only 210 pounds, a rather amazing 44 pounds under Part 103's limits. Americans fitting Dingo with a more powerful engine and high quality paint will weigh more but Rick and David both emphasized that it is easily possible to stay within Part 103 meaning no pilot medical is required nor are N-numbers.

The engine Rick and David like best is the Thor 260 Polini producing 36 horsepower. This much juice means spirited performance for Dingo even with the largest pilot the design can accommodate at 240 pounds. Since the seat is bolted to the aircraft, ballast is needed for the heaviest pilots, with the weight placed aft. If you are as light as David (160 pounds), you'll need ballast up front instead. Rick weighs 180 pounds; he made no mention of ballast. Polini is a popular choice for the lightest aircraft and boasts dual starting — hand-pull or electric — plus a centrifugal clutch yields an easier and smoother start.

The engine Rick and David like best is the Thor 260 Polini producing 36 horsepower. This much juice means spirited performance for Dingo even with the largest pilot the design can accommodate at 240 pounds. Since the seat is bolted to the aircraft, ballast is needed for the heaviest pilots, with the weight placed aft. If you are as light as David (160 pounds), you'll need ballast up front instead. Rick weighs 180 pounds; he made no mention of ballast. Polini is a popular choice for the lightest aircraft and boasts dual starting — hand-pull or electric — plus a centrifugal clutch yields an easier and smoother start.

Rick and David use a two-place Quicksilver for intro flights as a way to assure pilots can handle the very light Dingo. Rick indicated that even though Dingo offers responsive handling, he believes it is more stable than a Quicksilver. Since Quicks are widely known for docile performance, that is a substantial claim.

American pilots used to a huge variety of aircraft choices additionally asked about features such as brakes, floats, folding wings, and tricycle gear. Future Vehicles is evaluating all these options, however, that 254-pound Part 103 empty weight will limit how much a buyer can add.

Rick and David use a two-place Quicksilver for intro flights as a way to assure pilots can handle the very light Dingo. Rick indicated that even though Dingo offers responsive handling, he believes it is more stable than a Quicksilver. Since Quicks are widely known for docile performance, that is a substantial claim.

American pilots used to a huge variety of aircraft choices additionally asked about features such as brakes, floats, folding wings, and tricycle gear. Future Vehicles is evaluating all these options, however, that 254-pound Part 103 empty weight will limit how much a buyer can add.

A legal Part 103 ultralight for the mid-$20,000s has the potential to generate plenty of interest.

Sure, if you need to travel or carry a bunch of gear, or if you must be enclosed for comfort, you'll need to look beyond Dingo. However, for weekend fun or simply a 45-minute flight at the end of your workday, this sweet, affordable flying machine might be just the ticket.

A legal Part 103 ultralight for the mid-$20,000s has the potential to generate plenty of interest.

Sure, if you need to travel or carry a bunch of gear, or if you must be enclosed for comfort, you'll need to look beyond Dingo. However, for weekend fun or simply a 45-minute flight at the end of your workday, this sweet, affordable flying machine might be just the ticket.

This week

This week

For many years I've written about this sector and names like Searey, Seamax, and Aventura (all in nearby image) have long been the leading brands. Now the first two are in financial trouble and the last has decamped to Brazil from Florida. Whatever is going on, Vickers Wave may represent a breath of fresh air.

In articles last fall and this spring, I gave overviews of the entire LSA seaplane market (

For many years I've written about this sector and names like Searey, Seamax, and Aventura (all in nearby image) have long been the leading brands. Now the first two are in financial trouble and the last has decamped to Brazil from Florida. Whatever is going on, Vickers Wave may represent a breath of fresh air.

In articles last fall and this spring, I gave overviews of the entire LSA seaplane market ( "A frequently asked question I receive is, 'What is taking so long?'," begins Paul Vickers. "Given the scale and complexity of a project like this, it’s worth explaining some of the key challenges we’ve faced and the strategies we’ve employed to address them."

"The process of developing an aircraft like the Wave has spanned nearly 15 years (2009) — approximately one-third of my life," Paul continued. "The path to this stage has been characterized by sustained focus and incremental progress."

"A frequently asked question I receive is, 'What is taking so long?'," begins Paul Vickers. "Given the scale and complexity of a project like this, it’s worth explaining some of the key challenges we’ve faced and the strategies we’ve employed to address them."

"The process of developing an aircraft like the Wave has spanned nearly 15 years (2009) — approximately one-third of my life," Paul continued. "The path to this stage has been characterized by sustained focus and incremental progress."

Recalling his early days, Paul wrote, "For the first three to four years, I was the only person dedicated full-time to the Wave, working six to seven days a week." He was focused on ensuring the structural and aerodynamic integrity of the aircraft. Flight testing (

Recalling his early days, Paul wrote, "For the first three to four years, I was the only person dedicated full-time to the Wave, working six to seven days a week." He was focused on ensuring the structural and aerodynamic integrity of the aircraft. Flight testing ( New Zealand’s strict regulatory environment presented an additional set of challenges. The down-under country's Civil Aviation Authority (CAA), similar to the FAA, requires LSA manufacturers to meet General Aviation manufacturing standards. "Consequently," Paul continued, "our company must adhere to rigorous standards and navigate various certification obstacles, including following stringent test pilot requirements."

"Our approach from the beginning has been to construct the prototype with production tooling, molds, and processes," clarified Paul. "This approach aims to reduce variability in future production stages, though it requires significant up-front investment in research and development, creating production-ready tooling, and composite-structure molds. Many manufacturers prioritize design at the expense of manufacturability, but we have chosen to focus on both, with an emphasis on building production efficiencies from the outset."

New Zealand’s strict regulatory environment presented an additional set of challenges. The down-under country's Civil Aviation Authority (CAA), similar to the FAA, requires LSA manufacturers to meet General Aviation manufacturing standards. "Consequently," Paul continued, "our company must adhere to rigorous standards and navigate various certification obstacles, including following stringent test pilot requirements."

"Our approach from the beginning has been to construct the prototype with production tooling, molds, and processes," clarified Paul. "This approach aims to reduce variability in future production stages, though it requires significant up-front investment in research and development, creating production-ready tooling, and composite-structure molds. Many manufacturers prioritize design at the expense of manufacturability, but we have chosen to focus on both, with an emphasis on building production efficiencies from the outset."

Composite materials, particularly carbon fiber, pose additional complexity due to their variability. Unlike aluminium, for which structural properties and specifications are standardized and readily available, carbon fiber varies depending on the manufacturer. Each type of carbon fabric has unique characteristics based on the material’s weave, the machinery used in its production, and the proprietary resins applied by the supplier. When we receive the carbon fiber, further factors — such as the composition of the mold, oven types and curing cycles, and vacuum application techniques — affect the final product’s structural properties.

Each composite assembly undergoes rigorous testing. "We produce hundreds of test samples (coupons) in various weights and configurations, which are sent to certified labs," began Paul. "These samples are then tested across a range of environmental conditions, including standard daily temperatures, elevated temperatures, hot and wet conditions, and extreme cold. This testing yields 'material allowables' which guide the design and size of components to ensure compliance with our structural requirements. We repeat these tests with various adhesives to validate bonding integrity under similar environmental stresses."

Composite materials, particularly carbon fiber, pose additional complexity due to their variability. Unlike aluminium, for which structural properties and specifications are standardized and readily available, carbon fiber varies depending on the manufacturer. Each type of carbon fabric has unique characteristics based on the material’s weave, the machinery used in its production, and the proprietary resins applied by the supplier. When we receive the carbon fiber, further factors — such as the composition of the mold, oven types and curing cycles, and vacuum application techniques — affect the final product’s structural properties.

Each composite assembly undergoes rigorous testing. "We produce hundreds of test samples (coupons) in various weights and configurations, which are sent to certified labs," began Paul. "These samples are then tested across a range of environmental conditions, including standard daily temperatures, elevated temperatures, hot and wet conditions, and extreme cold. This testing yields 'material allowables' which guide the design and size of components to ensure compliance with our structural requirements. We repeat these tests with various adhesives to validate bonding integrity under similar environmental stresses."

"This technical and regulatory rigor provides a snapshot of what’s involved in bringing a greenfield aircraft design to life," Paul continued. "In addition to fundamental requirements, we have introduced unique features, such as automatic wing-folding, anti-flip landing gear, and water thrusters. Integrating these innovations on an amphibious aircraft, while staying within the weight constraints of the LSA category (

"This technical and regulatory rigor provides a snapshot of what’s involved in bringing a greenfield aircraft design to life," Paul continued. "In addition to fundamental requirements, we have introduced unique features, such as automatic wing-folding, anti-flip landing gear, and water thrusters. Integrating these innovations on an amphibious aircraft, while staying within the weight constraints of the LSA category (

When may first deliveries happen?

When may first deliveries happen? "We have developed new manufacturing techniques that lower cost, increase strength, and save weight, all helping us achieve the incredible useful load."

"We have developed new manufacturing techniques that lower cost, increase strength, and save weight, all helping us achieve the incredible useful load."

Lined up on the runway, I open the throttle to the stop. The Dynamic surges forward, my right thumb presses a small button at the base of the throttle quadrant and I push the lever further forward. In an instant there’s 15% more thrust and the speed tape really starts to roll. Ease back on the stick and we’re airborne after a very short ground roll and climbing away at well over 1200 fpm.

Lined up on the runway, I open the throttle to the stop. The Dynamic surges forward, my right thumb presses a small button at the base of the throttle quadrant and I push the lever further forward. In an instant there’s 15% more thrust and the speed tape really starts to roll. Ease back on the stick and we’re airborne after a very short ground roll and climbing away at well over 1200 fpm.

Those who’ve flown the plane say engine choice does make a noticeable difference in performance. P2008s are typically heavier than comparable LSAs. Pilots who’ve tried the 912 and 914 versions say the extra horsepower of the turbocharged Rotax greatly improves the plane’s rate of climb, especially on hot days.

Those who’ve flown the plane say engine choice does make a noticeable difference in performance. P2008s are typically heavier than comparable LSAs. Pilots who’ve tried the 912 and 914 versions say the extra horsepower of the turbocharged Rotax greatly improves the plane’s rate of climb, especially on hot days.

Look at the nearby renderings. A prototype is flying now in tethered radio-controlled flight. Two more development aircraft will follow in preparation for the coming Mosaic regulation. Galen said they expect to fit in as a helicopter or powered-lift aircraft; both categories are included in the proposed new rule.

Going this regulatory route means Velocitor does not have to meet Part 103's restrictive rules. This allows a strong fuselage with enough battery energy to give you a reasonable flight time. It also means the aircraft can be recharged with a single plug. Batteries don't have to be swapped out as on other entries.

Look at the nearby renderings. A prototype is flying now in tethered radio-controlled flight. Two more development aircraft will follow in preparation for the coming Mosaic regulation. Galen said they expect to fit in as a helicopter or powered-lift aircraft; both categories are included in the proposed new rule.

Going this regulatory route means Velocitor does not have to meet Part 103's restrictive rules. This allows a strong fuselage with enough battery energy to give you a reasonable flight time. It also means the aircraft can be recharged with a single plug. Batteries don't have to be swapped out as on other entries.

Eight motors on four booms offers safety redundancy; other models use up to 18 motors with a battery for each.

Velocitor's empty weight is about 500 pounds but it has four times more battery energy than other entries.

Eight motors on four booms offers safety redundancy; other models use up to 18 motors with a battery for each.

Velocitor's empty weight is about 500 pounds but it has four times more battery energy than other entries.

With headquarters in Eisenach, Germany, the company's primary production facility is now located in Sumperk, Czech Republic. For years, the Western European producer has been building aircraft in Kherson, Ukraine. Given daily news coverage, every American knows by now Ukraine has been in defense mode following the Russian invasion almost three years ago. After the situation became completely unworkable — Kherson was an early area to be bombed, then occupied by Russian troops — the company quietly removed tooling, inventory, raw materials, and even some workers to less hazardous facilities in the nearby Czech Republic.

With headquarters in Eisenach, Germany, the company's primary production facility is now located in Sumperk, Czech Republic. For years, the Western European producer has been building aircraft in Kherson, Ukraine. Given daily news coverage, every American knows by now Ukraine has been in defense mode following the Russian invasion almost three years ago. After the situation became completely unworkable — Kherson was an early area to be bombed, then occupied by Russian troops — the company quietly removed tooling, inventory, raw materials, and even some workers to less hazardous facilities in the nearby Czech Republic.

"We have recently moved production of the CT-series — including CTLSi and CT Super (nearby image), which continue to be popular worldwide — to our new partners in Kazakhstan. This allows us to focus more on the F2 at Sumperk,” said Daniel.

If you can't recall where Kazakhstan is, don't fret. Such remote fabrication has been used by Boeing and Airbus for many years. The parent company in Germany is permitted to sublet work to off-site facilities so long as they maintain control of the design and conduct regular oversight of production and quality control. After many years of doing exactly that in Ukraine, Flight Design is well equipped to pursue building its CT-series in Kazakhstan, Central Asia.

"We have recently moved production of the CT-series — including CTLSi and CT Super (nearby image), which continue to be popular worldwide — to our new partners in Kazakhstan. This allows us to focus more on the F2 at Sumperk,” said Daniel.

If you can't recall where Kazakhstan is, don't fret. Such remote fabrication has been used by Boeing and Airbus for many years. The parent company in Germany is permitted to sublet work to off-site facilities so long as they maintain control of the design and conduct regular oversight of production and quality control. After many years of doing exactly that in Ukraine, Flight Design is well equipped to pursue building its CT-series in Kazakhstan, Central Asia.

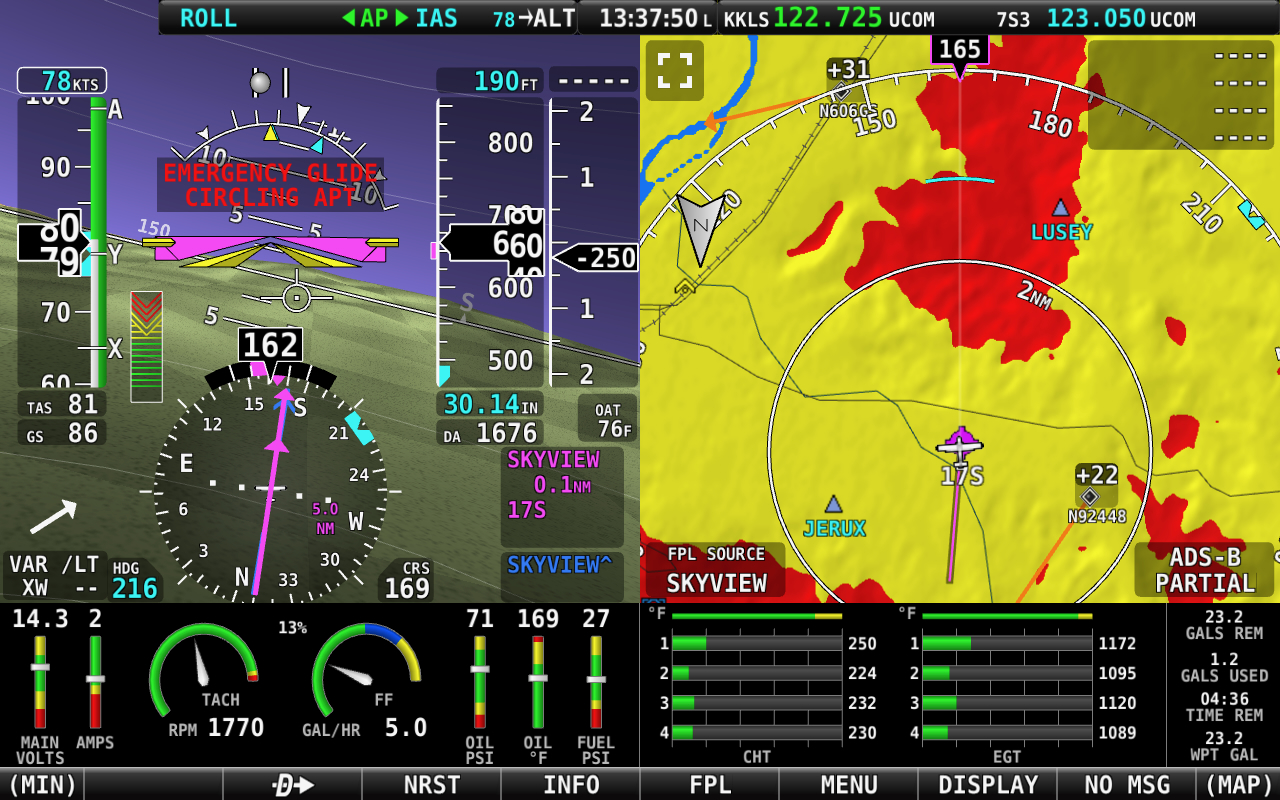

I probably shouldn’t admit this, but some features that come with the latest electronic flight instruments have left me a little, um, disinterested. Until I try them, that is. A good example is the concept of “safe glide” or even autoland. Garmin introduced both concepts a few years ago, though the full-autoland idea is more recent and limited to high-end aircraft where the system can control the engine directly. That’s not at my pay grade.

The more common version is what Garmin calls Smart Glide and, more recently, Dynon rolled out what it calls Emergency Glide. They work similarly: When commanded, they set up a controlled descent to the nearest viable airport and let the pilot concentrate on other things. To be honest, I was a bit meh about them as safety features. After all, you’re trained to set the airplane up for best-glide speed as soon as you recognize a power failure and all good pilots fly along considering which airports beneath them are reachable. Things like terrain-aware glide rings on MFDs and EFBs take much of the guessing out of that.

So I was skeptical until I flew with the Dynon version in my own airplane. To get this new functionality in the Dynon universe, you need to be running at least a Dynon HDX system—it is not offered for the Classic or Touch models—or one of the later AFS systems. You need a two-axis Dynon or AFS autopilot. There are a few other requirements, including an up-to-date database and the airplane’s best-glide speed entered into the setup menu. Moreover, you have to have the autopilot’s “expert” mode enabled; but this is what most do and there’s no cost involved, just a setting.

I probably shouldn’t admit this, but some features that come with the latest electronic flight instruments have left me a little, um, disinterested. Until I try them, that is. A good example is the concept of “safe glide” or even autoland. Garmin introduced both concepts a few years ago, though the full-autoland idea is more recent and limited to high-end aircraft where the system can control the engine directly. That’s not at my pay grade.

The more common version is what Garmin calls Smart Glide and, more recently, Dynon rolled out what it calls Emergency Glide. They work similarly: When commanded, they set up a controlled descent to the nearest viable airport and let the pilot concentrate on other things. To be honest, I was a bit meh about them as safety features. After all, you’re trained to set the airplane up for best-glide speed as soon as you recognize a power failure and all good pilots fly along considering which airports beneath them are reachable. Things like terrain-aware glide rings on MFDs and EFBs take much of the guessing out of that.

So I was skeptical until I flew with the Dynon version in my own airplane. To get this new functionality in the Dynon universe, you need to be running at least a Dynon HDX system—it is not offered for the Classic or Touch models—or one of the later AFS systems. You need a two-axis Dynon or AFS autopilot. There are a few other requirements, including an up-to-date database and the airplane’s best-glide speed entered into the setup menu. Moreover, you have to have the autopilot’s “expert” mode enabled; but this is what most do and there’s no cost involved, just a setting.