More from Aero as Day 3 closes. Because of the number on display — and because several readers asked — this post will focus on electric propulsion in two distinct forms. Whatever you think about electric as a means of lifting aircraft aloft, escaping its approach appears impossible. Experimentation is happening in all quarters. The following review is far from exhaustive; many other examples could be found at Aero Friedrichshafen 2019. Most agree that batteries are the weak link in the chain and despite repeated promises of annual increases in energy density of 5-8%, it hasn’t happened over ten years I’ve followed this fairly closely. That does not preclude certain effective uses, for example, local area primary flight training or aerobatic flying. Yet flying cross country on batteries remains somewhere in the future. Nonetheless, projects abound and solutions may be upon us. Here’s what I saw today. Hybrid Power from Tecnam, Rotax, and Siemens — I had no choice but to drop big names because these three powerhouses are joining forces on a hybrid system.

More from Aero as Day 3 closes. Because of the number on display — and because several readers asked — this post will focus on electric propulsion in two distinct forms. Whatever you think about electric as a means of lifting aircraft aloft, escaping its approach appears impossible. Experimentation is happening in all quarters. The following review is far from exhaustive; many other examples could be found at

More from Aero as Day 3 closes. Because of the number on display — and because several readers asked — this post will focus on electric propulsion in two distinct forms. Whatever you think about electric as a means of lifting aircraft aloft, escaping its approach appears impossible. Experimentation is happening in all quarters. The following review is far from exhaustive; many other examples could be found at  Beside taking the lead in this investigation, funded by the "European Union Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme,"

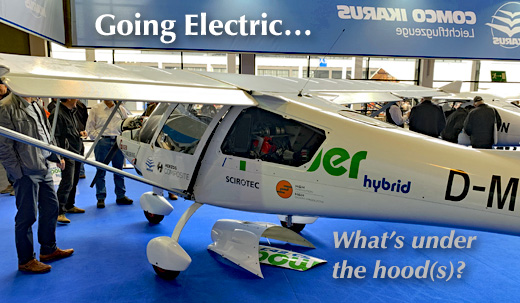

Beside taking the lead in this investigation, funded by the "European Union Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme,"  The big difference in this development compared to the H3PS project is that Toni flew the Comco Ikarus C-42 CS Elektro from his base near the factory to Aero. This hybrid is operating now. Technical information about the system was sparse on Toni's website, however, a German-language video (below) shows the aircraft operated essentially the same as its fossil fuel-powered counterparts.

When I spoke with Toni at the show. I recalled this man has has long experience with light trikes and hang glider propulsion systems based on electric power. He has gained valuable experience with these efforts and the results appear on his Comco C42C.

As an example of his state of development, the installation featured a cooling system but also a source of passenger comfort. A collar around the electric motor (white "doughnut" surrounding the motor) removes heat from the motor and channels it to the cabin. In the aft compartment, we saw a tidy installation of electric motor, generator, and a petrol fuel tank holding about 15 gallons.

The big difference in this development compared to the H3PS project is that Toni flew the Comco Ikarus C-42 CS Elektro from his base near the factory to Aero. This hybrid is operating now. Technical information about the system was sparse on Toni's website, however, a German-language video (below) shows the aircraft operated essentially the same as its fossil fuel-powered counterparts.

When I spoke with Toni at the show. I recalled this man has has long experience with light trikes and hang glider propulsion systems based on electric power. He has gained valuable experience with these efforts and the results appear on his Comco C42C.

As an example of his state of development, the installation featured a cooling system but also a source of passenger comfort. A collar around the electric motor (white "doughnut" surrounding the motor) removes heat from the motor and channels it to the cabin. In the aft compartment, we saw a tidy installation of electric motor, generator, and a petrol fuel tank holding about 15 gallons.

You may have already jumped to the point about those wings being exactly where the

You may have already jumped to the point about those wings being exactly where the  The company is now taking their smooth aircraft and powering it with an electric motor. They call the project B23 H55 Energic. The motor can deliver 90 kW (122 horsepower) for takeoff at 900 fpm and 65 kW (88 horsepower) for continuous cruise power at 125 mph. Onboard batteries can deliver one hour of endurance with a 20-minute reserve. Fully recharging will take only about 30 minutes. BRM estimates the cost of operation at $7/hour, less than the cost of one gallon of fuel at current European prices for avgas.

To repeat, this is far from a complete list of electric projects. Indeed, all of Hall A-7 at Aero Friedrichshafen was electric, with the giant Siemens company hosting a particularly large display. With multi-billion-euro companies like this involved — along with other giants of aviation and technology — it is clear that electric propulsion is on its way. How soon? What range is possible? What is the full cost …and saving? These and more questions remain to be answered but the technology is getting closer with every Aero. Look for more reporting on this at next

The company is now taking their smooth aircraft and powering it with an electric motor. They call the project B23 H55 Energic. The motor can deliver 90 kW (122 horsepower) for takeoff at 900 fpm and 65 kW (88 horsepower) for continuous cruise power at 125 mph. Onboard batteries can deliver one hour of endurance with a 20-minute reserve. Fully recharging will take only about 30 minutes. BRM estimates the cost of operation at $7/hour, less than the cost of one gallon of fuel at current European prices for avgas.

To repeat, this is far from a complete list of electric projects. Indeed, all of Hall A-7 at Aero Friedrichshafen was electric, with the giant Siemens company hosting a particularly large display. With multi-billion-euro companies like this involved — along with other giants of aviation and technology — it is clear that electric propulsion is on its way. How soon? What range is possible? What is the full cost …and saving? These and more questions remain to be answered but the technology is getting closer with every Aero. Look for more reporting on this at next  In 1943, Reichsmarschall Göring issued a request for design proposals to produce a bomber that was capable of carrying a 1,000 kilogram (2,200 pound) load over 1,000 kilometers (620 miles) at 1,000 kilometers per hour (620 mph) — the so-called "3×1000 project." Conventional German bombers could reach Allied command centers in Great Britain, but were suffering devastating losses from Allied fighters.

At the time, no aircraft could meet these goals. Junkers turbojet engines could provide the required speed but had excessive fuel consumption.

Walter and Reimer Horten concluded that a low-drag flying wing design could meet all of the goals. By reducing drag, cruise power could be lowered to the point where the range requirement could be met. They put forward their private project, the H.IX, as the basis for the bomber.

In 1943, Reichsmarschall Göring issued a request for design proposals to produce a bomber that was capable of carrying a 1,000 kilogram (2,200 pound) load over 1,000 kilometers (620 miles) at 1,000 kilometers per hour (620 mph) — the so-called "3×1000 project." Conventional German bombers could reach Allied command centers in Great Britain, but were suffering devastating losses from Allied fighters.

At the time, no aircraft could meet these goals. Junkers turbojet engines could provide the required speed but had excessive fuel consumption.

Walter and Reimer Horten concluded that a low-drag flying wing design could meet all of the goals. By reducing drag, cruise power could be lowered to the point where the range requirement could be met. They put forward their private project, the H.IX, as the basis for the bomber.

The Government Air Ministry approved the Horten proposal, but ordered the addition of two 30-mm cannons because they felt the aircraft would also be useful as a fighter as its estimated top speed was significantly higher than that of any Allied aircraft.

In short, flying wings are lean and make efficient use of the weight of their structure. That sounds like worthy qualifications for a Light-Sport Aircraft or Sport Pilot kit.

The Government Air Ministry approved the Horten proposal, but ordered the addition of two 30-mm cannons because they felt the aircraft would also be useful as a fighter as its estimated top speed was significantly higher than that of any Allied aircraft.

In short, flying wings are lean and make efficient use of the weight of their structure. That sounds like worthy qualifications for a Light-Sport Aircraft or Sport Pilot kit.

At this time, the company is not disclosing any pertinent data about the aircraft but I will be at

At this time, the company is not disclosing any pertinent data about the aircraft but I will be at