“It’s the people behind the wings that are the important aspect,” says Randy Snead of Gemini Powered Parachutes. His comment came in a reply to my question about why he prefers to work with only two suppliers of canopies for the powered parachutes he produces. His customers may say something similar thing about Randy.

As Randy continues to untangle lines, we can get a closer look at the Gemini Twin airframe. While at first glance, most powered parachute carriages seem pretty similar, each manufacturer designs their particular machine to meet the safety and comfort needs they deem most important for their customers. In the case of the Gemini Twin, Randy has incorporated the newer style roll bars coming up from the front axle to mate with the center frame, and he uses a chromoly steel landing gear as opposed to fibreglass rods to provide more strength to that important component. In addition, the Gemini Twin airframe is longer than most other models, offering more room for pilot and passenger in their separate seats. And, lastly, Randy was able to move the instrument panel closer to the pilot| an accommodation for older eyes!

Randy Snead, the principle owner of Gemini Powered Parachutes, untangles the line to his canopy as he prepares to take the Gemini Twin for a spin around the pattern at EAA AirVenture 2002.

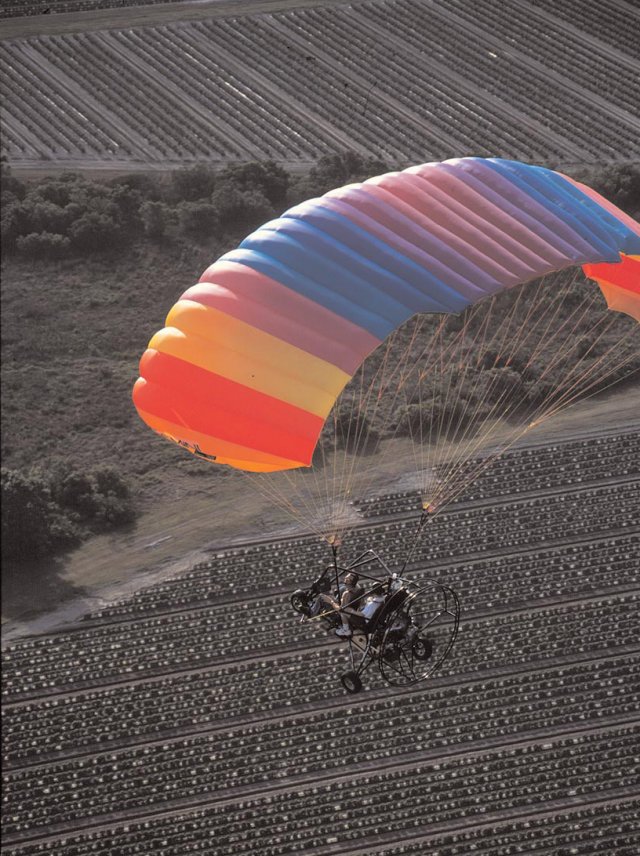

And, he’s off, with parachute fully inflated, he’s ready to add power and get airborne.

The romance of powered parachute flying lies in nearly unlimited visibility from either seat, and the ability to fly low and slow over various terrain. Like any open-air machine, powered parachutes allow their fliers to see and smell all that’s about them.

A New Powered Parachute From a Well-Known Leader

Randy Snead branches out into his own company

Once an important figure in

Buckeye Industries, Randy is

known to many as the man

who worked on the technical

side and performed flight-testing for

Buckeye. When the former company fell

into struggle (see Editor’s Note), Randy

departed to do his own thing. Customers

who followed state, “It’s the people

behind the company” that are important.

I can find no argument with this

approach; we all tend to trust those we

know.

In turn, Randy is assisted by people he

trusts. His wife, Fern, is the business

manager and also operates the parts and

ordering department for the young firm.

Their son, Jeremiah, has experience in

general aviation aircraft, weight-shift

trikes, and powered parachutes, and he’s

built many powered parachutes. In the

EAA way, Gemini Powered Parachutes is

a family affair.

Introducing Gemini

Powered Parachutes

“It’s the American way” say others.

The ease with which folks like Randy can

start off on their own demonstrates

America’s support of entrepreneurialism,

part of what makes this country great.

When times got tough, Randy set off to

make his own way.

Though the field is now crowded with

about 20 powered parachute producers,

Gemini Powered Parachutes views the

future as full of promise. “The industry

just started growing in the last five years,”

Randy says. “Before that, it was hardly

noticed.” Indeed, a decade ago only three

large producers existed: Paraplane, Six

Chuter, and Buckeye Industries.

“People like to fly low and slow,”

continues Randy, and I agree. While it is

true that many pilots will gravitate

toward the 130-mph little airplanes of

the proposed light-sport aircraft category,

others aren’t moved by speed or fully

enclosed cabins.

“Over the years, I’ve trained a dozen

or more airline pilots to fly powered

parachutes,” explains Randy. These pilots

are qualified to fly anything they want

(usually with incomes to allow most

purchases as well), and yet these 500-

mph aviators were drawn to the low-andslow

powered parachute arena.

Randy sees room for plenty of growth.

The mid-90s boom of powered

parachutes attracted plenty of other

producers. Some have created high

overhead to support their products, but

Gemini plans to survive any shakeout by

keeping its overhead low and by offering

good products at low prices with

reasonable delivery times.

“We have middle of the road pricing,”

says Randy, adding that his basic but

well-equipped model sells for $13,000,

and the electric start E-box version is

$13,600. A recently instituted Rotax price

increase bumped the numbers a few

hundred dollars. “As a small producer, we

had to pass that cost along to customers,”

Randy states.

Refining the Breed

When he departed Buckeye for his

own venture, Randy was experienced in

building powered parachutes, and he had

plenty of his own ideas to improve the

vehicles he had represented. “I took a little of everybody else’s best,” he

summarizes, “and then I added my own

ideas.”

He made the rear suspension beefier,

replacing the typical fiberglass landing

gear legs with chromoly ones. He also

used heavier wall steel tubing on the two

main front-to-rear rails under the seats.

Gemini Powered Parachutes worked to

assure more creature comforts by using

separate, supportive velour-covered seats.

Separate seats for each occupant seem

superior to the previously conventional

powered parachute seats that placed the

back of the pilot against his or her rearseat

occupant. Other companies have

also embraced this development, and

most pilots and passengers will probably

prefer separate seats. Shoulder belts at

each seat should secure the occupants

well.

“Older eyes need a little help,” Randy

correctly identifies, “so we moved the

instrument panel a bit closer to the

pilot.” Like other powered parachute

manufacturers, Gemini prefers the

electronic instrument packages that offer

lots of information, but some users feel

these are harder to read at a glance than

old-fashioned needle gauges. Randy also

moved all the controls closer, saying that

he “wants students to be able to reach

everything while securely belted in.”

The instrument panel and controls

can be located closer to the pilot thanks

to the addition of upper fuselage bars,

those large diameter tubes that run in

front of and above the occupants.

Powrachute, a competing manufacturer,

first popularized these bars, and now

these bars are popping up on powered

parachutes everywhere. Often referred to

as “rollover bars,” the tubes certainly

offer a measure of protection on landings

and while flying near ground obstacles,

although the industry tries not to draw

attention to such problems for liability

reasons.

In my experience of flying with this

tubing framework, I could easily see its

protective value, although it does

somewhat block visibility and erode that

hugely open feel of flying a powered

parachute.

A single strobe light comes standard to

help make you obvious to other aircraft,

while options include electric starting,

dual controls, dual strobes, a four-blade

Ivo prop, a choice of parachute parafoil

brands, a choice of airframe colors, and

factory assembly. Gemini Powered

Parachutes can also set you up with a

trailer to haul it all.

Operating a Gemini

Gemini’s “joystick throttle” comes

from the Buckeye design, which I flew a

few years ago. Because I now have

experience with other control systems in

newer powered parachutes, I asked Randy

about his continuing use of the joystick

throttle.

In my experience, thinking of the

throttle as a joystick proved distracting.

When I first flew a Buckeye Dream

Machine with this throttle arrangement, I

had an experience that I now find

humorous—I inappropriately used the

throttle and started to pull the joystick

back to stop a launch I felt wasn’t right.

In so doing, I added power and things

got worse before they got better.

(Nothing came of the misapplication of

power, and a few minutes later I was

soloing the Dream Machine without

problems.) The error was clearly mine,

but it showed how the joystick throttle

can introduce wrong responses from

pilots used to “pull-for-less-power”

throttles.

Randy has trained a number of pilots

with conventional throttle experience.

He says that he tells them to “forget the

word throttle.” He never terms the

joystick as a power control, instead

directing his transition students to think

of it as a “pitch control” or “stick.” In so

doing, he says his conventional pilot

students have never had control reversal

problems. A Piper Cherokee pilot himself,

Randy is also able to make the transition

by using his “not a throttle” mantra.

By making the “stick” function like it

does, Randy has helped it do double

duty. The same lever also steers the

chassis while on the ground. With the

stick linked to the nose wheel by

conventional pushrods, the Gemini

features push-right, go-right steering. This

is an improvement over the older

Buckeye model that had two levers: one

for power (or “pitch control”) and one for

steering. With the old steering lever, you

pushed forward to go right and pull aft to

go left. I found that counterintuitive, and

it was these two unorthodox controls

that were the source of my distraction in

that early takeoff.

Ready for Certification

While the proposed light-sport aircraft

(LSA) category with its FAA-mandated

consensus standards may be scaring a few

powered parachute manufacturers, it’s

not causing Gemini any concern. That’s

because Randy was involved with

Buckeye Industries’ attempt to qualify its

rig for Primary aircraft certification.

“If FAA had the money, [Buckeye]

could have had a certified aircraft five or

six years ago. All the work was done,”

recalls Randy. He feels a confluence of

events conspired to suffocate the effort.

ValuJet had just crashed into the south

Florida swamps, and FAA focused its

efforts on common carrier problems. The

Buckeye Primary aircraft effort was put

on the far back burner and never came to

the forefront again.

Too bad, perhaps. Randy had taken

Barry Valentine, then acting FAA

administrator, aloft at the Sun ’n Fun Fly-

In in 1996, and Valentine was highly

supportive of the certificated Buckeye,

says Randy. In those days, industry

comment on rules came from the “Big

Three” of powered parachute producers—

Paraplane, Six Chuter, and Buckeye—and

it was fairly easy to get agreement

between the three builders. Now, with 20

companies having input, Randy feels the

process of finding consensus has become

much more challenging.

In the mid-90s, Randy worked with

Ben Morrow to prepare pilots for flying a

Primary aircraft powered parachute. The

effort produced a document available

from FAA’s Kansas City office called the

Practical Test Standards for powered

parachute pilots. This effort may be used

in the new process of devising rules for

sport pilots. With FAA’s newest

regulation on the near horizon, Randy is

serving on an ASTM (American Society

for Testing and Materials) committee

that’s creating the consensus standards

for powered parachutes.

“The proposed light-sport aircraft

category could open up a lot of doors,”

Randy says. “Some entities can’t use our

aircraft today,” referring to

municipalities, police departments,

forestry services, and private corporations

that might find a use for powered

parachutes, because they are nervous

about the perceived lack of licensing,

insurance, and regulations. Under the

proposed sport pilot/light-sport aircraft

rules, some of these barriers could fall.

Randy will use his expertise to assure

the strength and quality of materials used

in light-sport aircraft category powered

parachutes. He says, “Our goal is for these

machines to last a long time. We don’t

want them to wear out in four to five

years,” noting that Cessna and Piper

build aircraft that last a very long time.

Randy went on to state his view of the

role of the powered parachute committee

of the ASTM effort. “LSA powered

parachutes won’t stall, will do 50- to 60-

degree banks without falling out of the

sky, and will land without parts flying

off.” The goals sound simple, but

involving a group of 20 manufacturers in

the process isn’t easy.

Gemini in the Skies

I felt one of the most important

questions I could ask Randy was how he

advises new pilots to choose the right

wing or parachute. In my experience

flying several other powered parachute

brands, I found the manufacturers were

not focused on wings. To me, the

competition appeared to be all about the

carriages. It turns out my view was

something of an oversimplification.

“Every two years, there’s a completely

new wing,” claims Randy. It may not be

the same as Moore’s law of computer

chips (regularly doubling processor

power), yet a new wing every couple

years certainly reveals growth in the

powered parachute community.

After I asked more questions about the

shapes and sizes of canopies, Randy

detailed the history of powered parachute

wings in the last five to six years. He says

the shapes have evolved from rectangular

to elliptical, though the rectangular

parachutes are still the most common

(and are the right choice for most

newcomers). Sizes have also changed

from 450 square feet to 550 or more. One company is offering a 610-square-foot

chute, according to Randy.

However, even the original

rectangular canopy is evolving. Randy

referred to the new Skybolt canopy from

High Energy Sports that he says can do a

360-degree turn in three seconds!

Indeed, performance has crept into

the equation. While most powered

parachutes fly at about the same speed—

from 26 to 34 mph—some have begun to

push the envelope. Elliptical canopies

include the granddaddy of the segment,

the Chiron wing from an Israeli

company. These higher aspect wings

offer a somewhat increased speed range

and snappier control line response.

When I was under the Chiron wing, it

was able to speed up in shallow dives and

reacted quickly to reversing turn inputs.

Randy says you usually select a wing

that is sized to the load you’ll put on it. If

you and your flying friend are of modest

build, a 500-square-foot wing might be

the best. This is the size Randy prefers for

the machines he flies. But I asked about

big guys with experience who want to go

faster. For them, Gemini will recommend

an elliptically shaped wing, not a smallersized

one (that is, one with less square

feet of area).

Gemini prefers to work with two wing

suppliers, Apco of Israel and High Energy

Sports of California. The U.S. company—

which I knew of long before they started

building powered parachute canopies—is

partnered with Bill Gargano, a parachute

design expert respected in the general

parachute community. Randy says, “I’ve

known Bill for many years, and I think

his work for powered parachutes is the

best available.”

Gemini would like to log sales of 200

units a year but predicts about half that

for the near term. Most ultralight

airframe makers would consider that a

terrific delivery performance. My regular

inquiries of Rotax distributors confirm

that powered parachute producers

remain the biggest buyers of that

company’s two-stroke engines, that

overwhelmingly being the 582.

Gemini predicts growth from new

interest overseas. “Israel is developing a

powered parachute community, and we

expect to make sales in France, Germany,

and Spain,” Randy adds. He senses that

interest in powered paragliders—the footlaunched,

backpack sister to powered

parachutes—may spur interest in U.S.-

style powered parachutes. “Europeans

also like wheels and creature comforts,”

Randy says.

Currently, France has a couple

domestic machines (one, the Sylphe, was

displayed at Sun ’n Fun 2002), otherwise

the Americans largely have the

international market to themselves, at

least for a time. Gemini hopes to get its

share.

To keep American and foreign buyers

coming, Randy’s mantra for Gemini is to

keep the prices modest, the aircraft

reliable, the service good, and the

delivery quick.

That sounds like a good way to please

customers to me.

Editor’s Note: Buckeye Industries, the

enterprise that once employed Randy

Snead, is now involved in a Chapter 11

bankruptcy filing. Buckeye Aviation is the

newly formed company that displayed

Buckeye powered parachutes at EAA

AirVenture Oshkosh 2002.

| Seating | 2, tandem/raised aft seat |

| Empty weight | 375 pounds |

| Gross weight | 935 pounds |

| Canopy Span | 38 feet 1 |

| Canopy Area | 500 square feet |

| Canopy Loading | 1.9pounds per square foot |

| Kit type | Fully Assembled |

| Notes: | 1 Assuming standard Apco Dovetail canopy |

| Standard engine | Rotax 582 |

| Power | 64 hp at 6,500 rpm |

| Power loading | 14.6 pounds per hp |

| Max Speed | 34 mph |

| Cruise speed | 34 mph |

| Never exceed speed | 70 mph |

| Rate of climb at gross | 600-800 fpm |

| Takeoff distance at gross | 150-500 feet |

| Landing distance at gross | 100-200 feet |

| Glide Ratio | 4:1 |

| Range (powered) | 85 miles |

| Standard Features | 65-hp Rotax 582 with oil injection, E-drive with electric start and battery, single stick control, independent seating, shoulder harness seat belts, 64-inch IvoProp propeller, chromoly main rails and upper fuselage bars, shock absorber suspension, steerable nosewheel, ready-to-fly canopy, single strobe light. |

| Options | Choice of 50-hp Rotax 503 engine (for reduced cost), electronic instruments, dual strobe lights, side storage bags, chrome prop spinner, 4-blade prop. |

| Construction | Aluminum 6061-T6 airframe, 4130 chromoly steel parts, and all AN hardware. Made in the USA by U.S.-owned company. |

Design

Cosmetic appearance, structural integrity, achievement of design goals, effectiveness of aerodynamics, ergonomics.

Pros – Using the best ideas in the powered parachute industry, designer Randy Snead has incorporated many features: protective upper fuselage bars, single control stick, electronic instruments, strategically placed canopy attach points, and individual seats with proper seat restraint. Sturdy, proven design using standard aircraft hardware throughout.

Cons – While using the best of other companies’ ideas, the Gemini Twin shows no earth-shattering innovations (though such new ideas don’t always work out; Snead’s design may be more likely to survive). New company with as-yet undefined longevity in the marketplace.

Systems

Subsystems available to pilot such as: Flaps; Fuel sources; Electric start; In-air restart; Brakes; Engine controls; Navigations; Radio; (items covered may be optional).

Pros – “Joystick” combines both throttle and nosewheel steering, the latter is quite intuitive. Standard 10-gallon fuel tank; cleaner fueling via a filler neck extending to left side of chassis. Pull starter position in open cockpit gives enough space for a hearty yank. Full access to all parts for repairs.

Cons – Of course, no flaps or trim to aid flight control. Determining when remaining fuel is low is not easy without optional instrumentation. No brakes (though needed less than on other ultralights).

Cockpit/Cabin

Instrumentation; Ergonomics of controls; Creature comforts; (items covered may be optional).

Pros – Comfort much improved with separate seats. Gemini uses an electronic info system to compactly provide data. Electric start can also be located on this panel with a kill switch (or other switches as owner prefers). Huge visibility from Gemini Twin. Instrument panel is mounted closer for “older eyes.”

Cons – Electric start is optional (about $700). Upper fuselage bars, while a welcome safety addition, slightly obstruct visibility. Little convenient space for additional instruments or a radio. Separate seats mean rear entry is slightly harder; seats do not adjust or move.

Ground Handling

Taxi visibility; Steering; Turn radius; Shock absorption; Stance/Stability; Braking.

Pros – Moving a Gemini Twin around the airport by hand is easy if you have the canopy in its carry bag. Huge visibility to check for traffic. Excellent suspension on the main gear. Solid stance on ground; helps maintain control until canopy is ready to lift. Steering stick is also power control making for an interesting “joystick.”

Cons – Lacks ground tow bar. Ground steering of a powered parachute with the canopy overhead is very limited and you must plan where you want to end up if others are using the landing area; you must also maintain enough speed to keep canopy inflated. No brakes, should you require them.

Takeoff/Landing

Qualities; Efficiency; Ease; Comparative values.

Pros – Once canopy is properly inflated, Gemini Twin takeoff is simple in the extreme. Visibility is massive on both takeoff and landing. Turning response is faster than most non-powered parachute pilots believe. Crosswinds are less the impediment than thought due to very short landing rolls; just land cross-runway. Approaching into small fields less challenging than most fixed-wing ultralights.

Cons – Power is the primary way to control approach descents; lose that power and you’ll rely only on the ability to modestly slow or flare the canopy. Little energy retention; smooth landings depend on power. No convex mirrors to help examine canopy inflation. Gas tank hangs rather low for landing in unimproved fields.

Control

Quality and quantity for: Coordination; Authority; Pressures; Response; and Coupling.

Pros – Turning control is reasonably responsive; if you combine footbar control with line pulls by hand, you can effect a fairly quick turn. Your legs are much stronger than your arms; you simply must learn foot coordination. Turns are intuitive; push the way you want to go. No adverse yaw.

Cons – You must learn to use the throttle and footbar slowly or swinging of the chassis occurs. Turning by foot is odd to most ultralight pilots and, indeed, it takes some familiarization.

Performance

Climb; Glide; Sink; Cruise/stall/max speeds; Endurance; Range; Maneuverability.

Pros – Gemini says the 65-hp Rotax 582 Twin climbs at 600 to 800 fpm. Speeds are always around 30 mph unless you select an elliptical canopy that Gemini Industries offers. If “performance” means doing superbly at flying low over the fields, the Gemini Twin is one of the best ultralight choices you can make.

Cons – Speeds are hardly controllable; small range of difference by power or dual footbar use. You aren’t going anywhere fast in a Gemini Twin with a 30-mph cruise. Performance in powered parachutes is so similar – they can all buy the canopies of other companies – that comparison is challenging. Glide is only about 4:1. Fuel mileage is lousy (that’s not why you fly a powered parachute).

Stability

Stall recovery and characteristics; Dampening; Spiral stability; Adverse yaw qualities.

Pros – Latest version of seatbelts neatly emerge from the seat and are now 4-point for best security (model tested had single shoulder belt). Strobe light included in base price, as are sturdy upper fuselage bars offering some protection against rollover or collision. Virtually stall-proof.

Cons – All powered parachutes can reportedly enter something the industry calls “meta-stable stall,” meaning a descending, hard-to-exit condition. Fortunately the Gemini Twin is built so tough that such a touchdown would be largely absorbed by the chassis. Chassis swings in response to power changes; you must make them slowly.

Overall

Addresses the questions: “Will a buyer get what he/she expects to buy, and did the designer/builder achieve the chosen goal?”

Pros – New company from an industry veteran; should survive an inevitable shakeout. Boss Randy Snead has experience with FAA certification, which should help if proposed Light-Sport Aircraft rule passes into law. Offers the best of many company ideas in a conventional package that buyers can trust. Several dealers already established around USA. Priced as a rather complete package.

Cons – Gemini Industries must work to set itself apart from others; by offering only mainstream features it could become lost in the crowd. New business, relying on name familiarity of Randy Snead. Company offers no Part 103 aircraft (yet).

I’m looking for a set of standard risers for my Gemini Twin asap.

Can you help please?

I recommend you contact EasyFlight.

I purchased Bimini 11 but there was no manual. Is a manual available .

Seek that help online using social media.