Quicksilver’s already-certified (under primary category) GT500 may be one of the first aircraft to win approval as an LSA.

The Australian Edge trike has already passed rigorous certification in its home country. Some builders believe this weight-shift machine will soon qualify for LSA.

A fine example of an LSA candidate is this FK9 from Germany. Fiberglass is used extensively, and it performs at the upper range of the proposed LSA specifications.

How do we evaluate light-sport aircraft?

The FAA’s proposed SportPlanes™ /light-sport aircraft (LSA) rule is being discussed in hangars across America. But it is also being discussed at airports all over Europe—more than you may think. The global reach of this initiative is visible by the large number of European suppliers aiming their sights on the huge U.S. market. Many believe they have an aircraft that fits the standard.

In the previous issue of KITPLANES®, you read Brian E. Clark’s summary of how European aircraft manufacturers are responding to LSA. In this issue, you can look at Barnaby Wainfan’s analysis of the aerodynamics of aircraft that meet the standard.

In concert, this column attempts to add information about LSA candidate aircraft that are flying now. I’ve had the pleasure to fly many of the aircraft that may one day call themselves LSAs. In that flying, I’ve learned some lessons about what you might expect and how to evaluate what interests you.

While you may not get to fly every LSA you are interested in buying, you will surely read a pilot’s report about them. My goal is to help you decipher those articles as well as the manufacturers’ sales brochures.

Airspeed

I once employed a flight instructor who told his students, “Only three things matter in a landing approach: airspeed, airspeed and airspeed.” His wisdom is not lost on the performance of LSAs. These aircraft must meet stall minimums of 44 knots (51 mph) clean and 39 knots (45 mph) when flaps, slats or other aerodynamic devices are deployed. LSAs may not cruise faster than 115 knots (132 mph).

How do you know if the aircraft genuinely meets those numbers? In the FAA’s certification plan, consensus standards must be reached by participating manufacturers and other parties regarding the certification of LSAs. Though industry leaders have been meeting for months to devise such a program, at this point a manufacturer need only state that the aircraft meets the standard. The FAA can investigate the manufacturer, but with the agency’s modest manpower budget such visits may be rare.

When aircraft reviewers fly an LSA candidate, they must rely on mounted instruments. In my experience, nearly every airspeed indicator is off to some degree—more so when the angle of attack is quite high as in stalls. Writers can be fooled. Each aircraft is unique. For example, designs that seat you far out in front (such as the Drifter) look different in stall than a fully enclosed aircraft with a conventional instrument panel. Deck angles in stall also look quite different from aircraft to aircraft.

I’ve tried GPS units to verify airspeeds, but they respond too slowly at the moment of stall (though they do well for cruise speed evaluations). The only way to gain an accurate stall speed is to use a pivoting-head pitot that points straight ahead no matter what angle of attack the aircraft has. Preferably, this pitot is mounted at the wingtip away from disturbances from the fuselage and propeller. The best results will also be found with a long-line trailing static source using a wind-protected vent for the ASI. Such appendages may be mounted by a factory establishing proof, but they are not practical for 1- to 2-hour flight tests.

How It Handles

How an aircraft handles has some effect on how writers evaluate qualities. For example, smoothness is not just a good attribute in normal flying, it is essential in evaluation flying. The controls of every aircraft are slightly different, so it can take some time to perform graceful movements with an aircraft’s controls.

When I perform power-off stalls, I try to maintain a consistent technique. Many test pilots use a 1 knot per second pace to decelerate into stall, but I believe the number is less important for a reviewer than consistency. Therefore, evaluators with more experience may be able to judge more accurately. Nonetheless, without a floating pitot and trailing static source, the reviewer cannot depend on the number showing on the ASI.

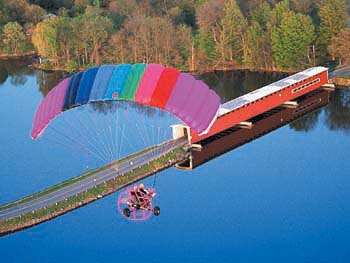

Some aircraft that will qualify as LSAs will have non-standard controls. This category includes trikes, powered parachutes, gyroplanes and airships. If you’re already flying one, you’re fully aware of the differences. It’s when you switch that problems can arise.

The LSA candidates I’ve flown have ranged throughout the spectrum. Stalls on a trike behave essentially the same even though they may go into the maneuver differently than a three-axis design. However, a powered parachute doesn’t stall in the usual understanding of that term (though they can reach something called a meta-stable stall).

For varying aircraft, the challenge for a writer is to write for his or her audience and at the same time inform pilots of different aircraft. Three-axis pilots looking at delta-winged trikes flown by weight shift need to read consistent reviews despite different control techniques.

Verifying Stability

So the Whizbang Aircraft Company salesman told you, “Sure, our Speedster stalls at 39 knots, and it cruises at 115 knots.” How do you know for certain?

You don’t know. Does it truly matter if the stall is 42 knots or the top speed is 110 knots? If you are satisfied with the aircraft in other ways, what difference do a few knots make? Very little. This fact also applies to certified aircraft—Cessna 172s don’t all stall identically. However, if the stall is 55 knots, your ability to land in small or rough fields might be compromised. An LSA might also prove too fast.

Manufacturers are disciplined to provide good data by several forces. First, the manufacturer of an LSA must build and fly an example of the kit or fully built LSA it wishes to sell. It must also follow ASTM consensus standards about how it verifies stall, weight, cruise and other attributes that define LSAs. Because it must agree to allow an audit by the FAA when it applies for an LSA certificate, the manufacturer is subject to inspections that will ask precisely how it proved the stall speed among other points.

Second, any manufacturer hoping to build a significant business will want insurance. Most pilots who buy a $50,000-$60,000 aircraft will insist on coverage against its loss. All pilots who finance their LSA will require insurance. Therefore, inspectors from willing insurers will verify that a given LSA meets the standard.

Third, the rubber truly meets the road in U.S. courts of law. Even if a manufacturer never goes to trial, the threat of legal action will keep any responsible manufacturer adhering to the standards.

While uncertainties will always exist, several mechanisms are in place to help consumers. I believe most LSA suppliers are honest, hard-working folks selling well-engineered aircraft. This is the light aircraft industry’s chance to show that it is worthy of the rights enjoyed by general aviation aircraft. I hope they succeed and that you are delighted to own a LSA. Nevertheless, buyer beware is still good advice.

Leave a Reply