Probably like a lot of you, I enjoy different kinds of flying but if asked to state one favorite, it’s an easy question to answer.

You may never have felt such thing and you may be hesitant about launching into the air in an aircraft that will allow only one approach and landing per flight; no exceptions. However, for those entranced by manipulating wisps of air to rise upward, a machine like Pipistrel’s Sinus is a thing of beauty.

Want to learn more? Let’s take a sample soaring flight. Even better, let’s investigate wave soaring.

Riding the Wave

Some years back I flew with Pipistrel dealer, Robert Mudd, to more than 17,000 feet. Conditions would have allowed us to soar even higher but at Flight Level 180, you enter Class A airspace and we were not prepared for that. Lift was abundant, though, so we had to go find sinking air to stay out of controlled space.

Robert continues to be a soaring enthusiast, hailing from New Mexico. He relates the following story about flying a wave near Albuquerque. If you aren’t sure what wave is, read on.

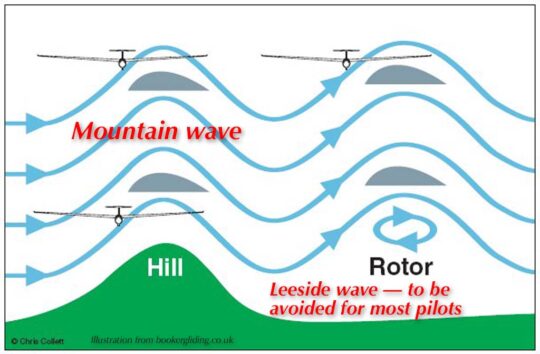

Knowing about waves can help you better negotiate mountain flying.

“We took off about 10:15 AM and climbed west-northwest under Rotax power. Our home field elevation is 6,200 feet.

“The orientation of the wind aloft was not the best for wave to form. An ideal wind direction is 260 to 280 degrees so as to be perpendicular to the Sandia mountains, which rise to 10,500 feet. The wave was forecast to be at the northern end of the Sandia range, and be at an angle to the mountains. Wind aloft was about 230 degrees, not ideal by any means. This would be a good test of John’s forecasting method.

“We continued on a north-northwest track, climbing modestly at about 1.5 to 2 knots, about 150-200 feet per minute. The forecast was for stronger lift ahead so we continued. Sure enough, just where John had forecast stronger conditions, we found that. The best climb rate we saw was 3 knots or about 300 feet per minute. We stopped the climb at 17,910 feet. We could have gone higher, I think to at least 20,000 feet, but the wave window was not open.

“We turned around and more or less followed our track back, still in wave, but staying well below 18,000 feet.

“The view was fantastic. As we flew out of the region of better lift we started a long slow decent and turned slightly to the southeast toward home.

“We landed after 1.25 hours of flight time, about an hour of which was power off. Naturally, the landing was done power off. As we cleared the runway I un-feathered the prop, started the motor and taxied to the hangar.

“This illustrates the potential of research that can be done in a touring type motorglider. Because both pilot and researcher were side by side, coordinating the flight path was easy (unpowered sailplanes almost always have tandem seating). We were able to motor right to the area we wanted to explore, and, of course. always had a safety out with the motor.

“All in all, it was a flight to remember for the research, fellowship, and the fun of it.”

—Robert Mudd, October 2021

TECHNICAL SPECIFICATIONS

Pipistrel Sinus

LSA Motorglider

- Wingspan — 49 feet, 1.5 inches

- Wing Area — 132 square feet

- Length — 24 feet, 1 inch

- Height — 6 feet

- Maximum Takeoff Weight — 1,213 pounds

- Standard Empty Weight — 644 pounds (typical weight 661 pounds)

- Useful Load — 569 pounds

- Payload (with full fuel) — 471 pounds

- Stall Speed (best flaps) — 35 knots

- Maneuvering Speed — 76 knots

- Maximum Rate of Climb — 1,063 feet per minutes at 62 knots

- Minimum Sink Rate (a key soaring term) — 217 feet per minute

- Takeoff Ground Roll — 433 feet

- Glide Ratio — 27:1

- Power Cruise — 110 to 115 knot with 80 horsepower Rotax 912

- Fuel Capacity — 15.9 gallons

- Fuel in optional long-range tanks — 24. 6 gallons

- Fuel Consumption — 3.1 gallons per hour at 110 knots

- Configuration — Available in tail dragger or nosewheel

- Endurance — up to 7.5 hours

- Maximum Range — 850 nautical miles

- Propeller — Feathering propeller option (approved for LSA motorgliders)

- Cockpit Width — 44 inches

- Baggage — 55 pounds capacity with external access option

* You can also soar leeside wave but this is for experts only.

Here’s our video with Rand Vollmer. Hear from a Sinus expert about this high performing LSA motorglider.

David, actually there is wave soaring in OK. The site was found by Randy Teel.

It is Talihina. Randy and some others have made some impressive flights there.

You are not too far from Moriarty either. So consider basing you motorglider here for a few weeks and watch the weather. Commute back and forth. We actually get wave year around but the best in in late winter and early spring.

Wave does not always need mountains to form. I have seen wave over Chicago and Central Ohio.

Robert Mudd

Thanks for the good info!

I would love to buy one of these models. I am a licensed commercial pilot, however these seem to be “out of my price range.” Are there any used Pipistrels that you are aware of?

Thank you

I do not personally know about specific aircraft for sale, Bill, but I am sure Pipistrel dealers have ideas; use this link or other links in the article.

It is true that any motorglider, even a LSA motor glider, tends to be valued higher than conventional fixed wing aircraft because of their special features and capabilities. (Seaplanes also share this trait.) Nonetheless, a few of these have been in the country for a while, and I’m sure some of them are for sale at prices less than brand new. Good luck!

Hi Bill,

We had a Sinus sold a couple weeks ago, but none on the market right now that I know of. I would be happy to let you spec out an order form so that you could at least compare pricing when preowned Sinus come on the market. Please give me a call or send email describing your desires.

I will keep an eye out on our used market.

I would love to try wave soaring. I own a Sundancer Motorglider and fly it out of Wiley Post in Oklahoma City. The only lift I’ve found is from thermals. Is there a website that shows John Wahl’s wave forecasts?

Thanks,

David

I recommend you contact Wave Soaring Adventures. It seems to be their focus. Good luck. Have fun!

David, actually there is wave soaring in OK. The site was found by Randy Teel.

It is Talihina. Randy and some others have made some impressive flight there.

You are not too far from Moriarty either. So consider baseing you morotglider here for a few weeks and watch the weather. Commute back and forth. we actually get wave year around but the best in in late winter and early spring.

Wave does not always need Mountains to form. I have seen wave over Chicago and Central Ohio.

Robert Mudd

While much is made of the altitude reached on this flight, almost 18,000 above sea level, it is not an uncommon altitude for gliders flying out of Moriarty, or even many other western USA sites. We regularly climb in thermals to 18,000, and have to stop the climb there.

As Dan has mentioned centering a good thermal and seeing climb rates in excess of 800 fpm is a real thrill. Most power pilots do not like to fly in bumpy conditions, glider pilots look for those conditions because we understand the energy existing there and how to exploit it.

Flying gliders makes you a better pilot, no matter what ratings you hold. especially flying them cross country.