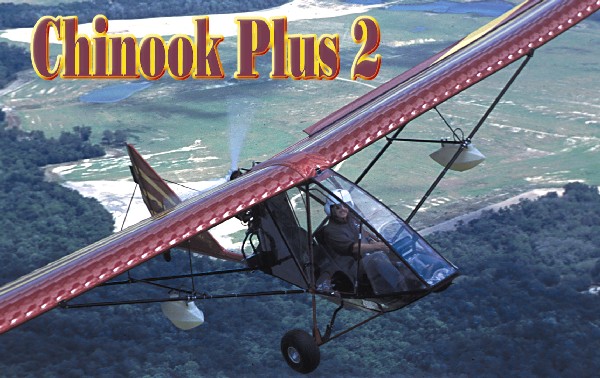

Then… In the 1990s, a pair of Canadian aircraft dominated the light aviation market in America’s neighbor to the north. The two planes are known to many Americans: Beaver and Chinook. Thanks to a rescue by second owner ASAP many years ago, both continued to be manufactured in Canada’s West. Long-departed Birdman Enterprises did a fine job of originating the Chinook. When ASAP took over, Canadians and ultralight enthusiasts in many places celebrated ongoing support of this aircraft. Hundreds of Chinooks were built. That is now rather distant history. Bringing Chinook not only into the present day but also into the USA is the Aeroplane Manufactory. …and Now For several years, ASAP sold the Chinook Plus 2, tagging the two-seater model with the “Plus” suffix after ASAP’s team improved and refined the aircraft following their acquisition. In more modern times, after purchasing the Chinook design rights and inventory in 2013 (five semi loads’ worth!), Aeroplane Manufactory brought the north-of-the-border design way down south to the Houston, Texas area.

Thanks to a rescue by second owner ASAP many years ago, both continued to be manufactured in Canada's West.

Long-departed Birdman Enterprises did a fine job of originating the Chinook. When ASAP took over, Canadians and ultralight enthusiasts in many places celebrated ongoing support of this aircraft. Hundreds of Chinooks were built.

That is now rather distant history. Bringing Chinook not only into the present day but also into the USA is the

Thanks to a rescue by second owner ASAP many years ago, both continued to be manufactured in Canada's West.

Long-departed Birdman Enterprises did a fine job of originating the Chinook. When ASAP took over, Canadians and ultralight enthusiasts in many places celebrated ongoing support of this aircraft. Hundreds of Chinooks were built.

That is now rather distant history. Bringing Chinook not only into the present day but also into the USA is the  In more modern times, after purchasing the Chinook design rights and inventory in 2013 (five semi loads' worth!), Aeroplane Manufactory brought the north-of-the-border design way down south to the Houston, Texas area.

"We at Aeroplane Manufactory, with almost 50 years of aviation experience, strongly desire to balance the price of building and flying your own aircraft with safety, reliability and affordability," said John Couch, a deeply-experienced aviator leading the Texas kit builder with his wife, Kim. "The Chinook line of aircraft has been on the market for over 35 years, with over 900 aircraft flying in more than 30 countries."

Careful to give credit where due, John noted, “Kim is more than my equal partner; she does all research, shipping, packing and handling, and purchasing.” He called her “my own Olive Ann Beech, who even works in the factory making parts!”

In more modern times, after purchasing the Chinook design rights and inventory in 2013 (five semi loads' worth!), Aeroplane Manufactory brought the north-of-the-border design way down south to the Houston, Texas area.

"We at Aeroplane Manufactory, with almost 50 years of aviation experience, strongly desire to balance the price of building and flying your own aircraft with safety, reliability and affordability," said John Couch, a deeply-experienced aviator leading the Texas kit builder with his wife, Kim. "The Chinook line of aircraft has been on the market for over 35 years, with over 900 aircraft flying in more than 30 countries."

Careful to give credit where due, John noted, “Kim is more than my equal partner; she does all research, shipping, packing and handling, and purchasing.” He called her “my own Olive Ann Beech, who even works in the factory making parts!”

"We offer the lowest price for the highest performing aircraft in our class," John boasted. "The quality of our parts and kits and ease of construction is paramount to our business and your success as a builder/pilot. Your dream and passion for building and flying your own aircraft is a shared dream and passion of ours. We are with you throughout the building process from start to finish."

John is an airline transport rated pilot who has been a flight instructor for 41 years. He has taught flying in the U.S., UK, Australia, and the United Arab Emirates. Learning to fly gliders when he was barely a teenager, John was flying a Lear 25 at the tender age of 24. He reports having flown 140 aircraft in his long career.

"We offer the lowest price for the highest performing aircraft in our class," John boasted. "The quality of our parts and kits and ease of construction is paramount to our business and your success as a builder/pilot. Your dream and passion for building and flying your own aircraft is a shared dream and passion of ours. We are with you throughout the building process from start to finish."

John is an airline transport rated pilot who has been a flight instructor for 41 years. He has taught flying in the U.S., UK, Australia, and the United Arab Emirates. Learning to fly gliders when he was barely a teenager, John was flying a Lear 25 at the tender age of 24. He reports having flown 140 aircraft in his long career.

In their days, ASAP added a full Lexan enclosure for the Chinook Plus, making a virtual greenhouse surrounding the pilot and passenger with many square feet of clear plastic offering an unlimited view. In colder northern climates, that enclosure provides a reasonably comfortable environment.

Entering a Chinook means lifting yourself over a gap from the outside edge of cockpit to the seat. However, once you swing into position, you’ll love the roominess. Even with a rear seat passenger’s feet on rudder pedals right alongside your seat, space is plentiful. If you’re a wide pilot, this machine might be your dream.

As proof, John reports he is 6 foot 7 inches tall and weighs 220 pounds. He fits with room to spare. Since

In their days, ASAP added a full Lexan enclosure for the Chinook Plus, making a virtual greenhouse surrounding the pilot and passenger with many square feet of clear plastic offering an unlimited view. In colder northern climates, that enclosure provides a reasonably comfortable environment.

Entering a Chinook means lifting yourself over a gap from the outside edge of cockpit to the seat. However, once you swing into position, you’ll love the roominess. Even with a rear seat passenger’s feet on rudder pedals right alongside your seat, space is plentiful. If you’re a wide pilot, this machine might be your dream.

As proof, John reports he is 6 foot 7 inches tall and weighs 220 pounds. He fits with room to spare. Since

Today, John said that a "60 mph cruise" is achieved despite the draggy but highly shock absorbing DR gear (nearby image).

"Dan Reynolds is the designer of the 'DR' gear option for our Chinook line of aircraft," noted John. "Dan is a bush pilot in the Yukon, Canada and flies several modified Chinooks. He broke the world record for shortest landing in the LSA class at Valdez in 2018, and came in second place with the shortest landing at the 2020 Lone Star STOL competition in Gainesville, Texas."

Among the several changes John has created, flaperons have been broadened. With its hard-working wing (note close rib spacing), he reports Chinook performs as well as a purpose-built STOL aircraft.

"Chinook Plus 2 is typically equipped with a 65-horsepower

Today, John said that a "60 mph cruise" is achieved despite the draggy but highly shock absorbing DR gear (nearby image).

"Dan Reynolds is the designer of the 'DR' gear option for our Chinook line of aircraft," noted John. "Dan is a bush pilot in the Yukon, Canada and flies several modified Chinooks. He broke the world record for shortest landing in the LSA class at Valdez in 2018, and came in second place with the shortest landing at the 2020 Lone Star STOL competition in Gainesville, Texas."

Among the several changes John has created, flaperons have been broadened. With its hard-working wing (note close rib spacing), he reports Chinook performs as well as a purpose-built STOL aircraft.

"Chinook Plus 2 is typically equipped with a 65-horsepower

After many years of providing flight instruction, John's specialty is transitioning from tricycle gear aircraft to tailwheel, short field landings, takeoffs over obstacles and upset training. John also teaches transition courses from general aviation to Light-Sport Aircraft. He gives several flight reviews for airmen each year."

"The Gloster School of Special Flying (GSSF) is designed to teach unique skills from beginner students as well as advanced pilots."

After many years of providing flight instruction, John's specialty is transitioning from tricycle gear aircraft to tailwheel, short field landings, takeoffs over obstacles and upset training. John also teaches transition courses from general aviation to Light-Sport Aircraft. He gives several flight reviews for airmen each year."

"The Gloster School of Special Flying (GSSF) is designed to teach unique skills from beginner students as well as advanced pilots." The Beaver and Chinook ultralight-like aircraft are arguably two of the bestknown

lightweight designs coming from Canada. Aircraft Sales and Parts, more

commonly known as ASAP, is the company that rescued and now manufactures

and sells these designs, along with a powered parachute from its sister company,

Summit Powered Parachutes. The tale of ASAP's involvement with the Chinook

and Beaver offers insight into ultralight progress - Canadian style.

The Beaver and Chinook ultralight-like aircraft are arguably two of the bestknown

lightweight designs coming from Canada. Aircraft Sales and Parts, more

commonly known as ASAP, is the company that rescued and now manufactures

and sells these designs, along with a powered parachute from its sister company,

Summit Powered Parachutes. The tale of ASAP's involvement with the Chinook

and Beaver offers insight into ultralight progress - Canadian style.

Perhaps the most famous ultralight

to come out of Canada is the Beaver.

With a reported 2,200 flying units

since the early 1980s, it's a successful

design. However, due to corporate

missteps by the companies that

owned the brand, the Beaver series

was nearly lost. Originally, the Beaver

models were manufactured by

Spectrum Aircraft Inc. Reorganization

left the ultralight in the hands

of a company called Beaver RX Enterprises.

In 1993, that company closed

its doors and stranded thousands of

Beaver aircraft owners, along with

all the dealerships that sold and serviced

them.

Perhaps the most famous ultralight

to come out of Canada is the Beaver.

With a reported 2,200 flying units

since the early 1980s, it's a successful

design. However, due to corporate

missteps by the companies that

owned the brand, the Beaver series

was nearly lost. Originally, the Beaver

models were manufactured by

Spectrum Aircraft Inc. Reorganization

left the ultralight in the hands

of a company called Beaver RX Enterprises.

In 1993, that company closed

its doors and stranded thousands of

Beaver aircraft owners, along with

all the dealerships that sold and serviced

them.

Luckily, Brent and Paulette Holomis,

the owners of ASAP, stepped in

to fill this void. Having already saved

the Chinook ultralight following the

closing of Birdman Enterprises, ASAP

was in position to help. Brent explains,

"Because the Chinook Plus 2 is

similar in construction to the Beaver,

we were approached by some Beaver

dealers and customers to see if we

could somehow provide them with

parts for their existing aircraft."

The company did more than just

take over these disappearing designs.

Thanks to focus and a related machine

shop business, ASAP was able

to make improvements on both airplanes.

Today, both Chinook and the

Beaver have the suffix Plus added to

them to denote the additional design

work done.

Luckily, Brent and Paulette Holomis,

the owners of ASAP, stepped in

to fill this void. Having already saved

the Chinook ultralight following the

closing of Birdman Enterprises, ASAP

was in position to help. Brent explains,

"Because the Chinook Plus 2 is

similar in construction to the Beaver,

we were approached by some Beaver

dealers and customers to see if we

could somehow provide them with

parts for their existing aircraft."

The company did more than just

take over these disappearing designs.

Thanks to focus and a related machine

shop business, ASAP was able

to make improvements on both airplanes.

Today, both Chinook and the

Beaver have the suffix Plus added to

them to denote the additional design

work done.

ASAP's array of computer-controlled

machines allows the company

to build parts in-house when many

other manufacturers must go outside

to obtain similar quality hardware.

Those who compare ASAP to Quicksilver

Aircraft, which also has significant

machining capability, are close

to the mark.

ASAP operates out of two locations.

The company manufactures

all parts and components for both

Chinooks and Beavers at its headquarters

in St. Paul, Alberta, Canada.

Another location, in Vernon,

British Columbia, handles all airplane

inquiries and processes part

orders. Technical support and new

product testing is also conducted

in Vernon.

ASAP's array of computer-controlled

machines allows the company

to build parts in-house when many

other manufacturers must go outside

to obtain similar quality hardware.

Those who compare ASAP to Quicksilver

Aircraft, which also has significant

machining capability, are close

to the mark.

ASAP operates out of two locations.

The company manufactures

all parts and components for both

Chinooks and Beavers at its headquarters

in St. Paul, Alberta, Canada.

Another location, in Vernon,

British Columbia, handles all airplane

inquiries and processes part

orders. Technical support and new

product testing is also conducted

in Vernon.

ASAP also has four corporate divisions:

Steel Breeze Powered Parachutes

(www.SteelBreeze.ca), UL Parts

(www.ULParts.com), PPC Canopies

(www.PPCCanopies.com), and Summit

Powered Parachutes (www.Summit-

PPC.com).

The Chinook

Before being rescued by ASAP, some

700 Chinooks had been manufactured

by Birdman Enterprises,

which did a great job of originating

this machine. Canadians in particular,

and ultralight enthusiasts all

over the world, celebrated ASAP's

support of this unique light aircraft

when the company took over the

design in 1988, and reintroduced

the design in 1989.

Though the Chinook's wide cockpit

gives it a pudgy appearance from

some vantage points, the design slips

through the air quite well. It has

light and powerful ailerons, which

makes it easy to guide through the

air. In general, the plane's handling

is quite pleasant despite, or perhaps

because of, its unorthodox shape.

ASAP also has four corporate divisions:

Steel Breeze Powered Parachutes

(www.SteelBreeze.ca), UL Parts

(www.ULParts.com), PPC Canopies

(www.PPCCanopies.com), and Summit

Powered Parachutes (www.Summit-

PPC.com).

The Chinook

Before being rescued by ASAP, some

700 Chinooks had been manufactured

by Birdman Enterprises,

which did a great job of originating

this machine. Canadians in particular,

and ultralight enthusiasts all

over the world, celebrated ASAP's

support of this unique light aircraft

when the company took over the

design in 1988, and reintroduced

the design in 1989.

Though the Chinook's wide cockpit

gives it a pudgy appearance from

some vantage points, the design slips

through the air quite well. It has

light and powerful ailerons, which

makes it easy to guide through the

air. In general, the plane's handling

is quite pleasant despite, or perhaps

because of, its unorthodox shape.

The Chinook was not always fully

enclosed; ASAP added a full Lexan enclosure

for the Chinook Plus, making

a virtual greenhouse surrounding the

pilot and passenger with many square

feet of clear plastic offering an unlimited

view. Even in colder northern climates,

that enclosure provides a reasonably

comfortable environment.

Entering a Chinook means lifting

yourself over about 6 inches of structure,

which could prove a bit challenging

for less flexible aviators, but

once you swing into position you'll

love the roominess. Even with a rearseat

passenger's feet on rudder pedals

right alongside your seat, space is

plentiful. If you have some extra girth

yourself, the Chinook Plus might accommodate

you more comfortably

than some other designs.

ASAP offers the Chinook with the

Rotax 503 or 582 engines, the HKS

700E, or the more powerful Rotax 912.

The Beaver

The Chinook was not always fully

enclosed; ASAP added a full Lexan enclosure

for the Chinook Plus, making

a virtual greenhouse surrounding the

pilot and passenger with many square

feet of clear plastic offering an unlimited

view. Even in colder northern climates,

that enclosure provides a reasonably

comfortable environment.

Entering a Chinook means lifting

yourself over about 6 inches of structure,

which could prove a bit challenging

for less flexible aviators, but

once you swing into position you'll

love the roominess. Even with a rearseat

passenger's feet on rudder pedals

right alongside your seat, space is

plentiful. If you have some extra girth

yourself, the Chinook Plus might accommodate

you more comfortably

than some other designs.

ASAP offers the Chinook with the

Rotax 503 or 582 engines, the HKS

700E, or the more powerful Rotax 912.

The Beaver

As it had done with the Chinook,

ASAP added value to the Beaver

RX550 by finishing the wing in conventional

dope and fabric (Ceconite),

rather than the original pre-sewn Dacron

envelopes. Using Ceconite increases

manufacturing time and adds

quite a few pounds (with paint), but

it lasts much longer, especially when

an aircraft is stored outside. With the

conversion to the Ceconite wing covering

also came a change in rib spacing

from 18 or 20 inches apart to 6

inches apart, which allows the wing

to hold its airfoil shape better and improves

performance slightly.

As it had done with the Chinook,

ASAP added value to the Beaver

RX550 by finishing the wing in conventional

dope and fabric (Ceconite),

rather than the original pre-sewn Dacron

envelopes. Using Ceconite increases

manufacturing time and adds

quite a few pounds (with paint), but

it lasts much longer, especially when

an aircraft is stored outside. With the

conversion to the Ceconite wing covering

also came a change in rib spacing

from 18 or 20 inches apart to 6

inches apart, which allows the wing

to hold its airfoil shape better and improves

performance slightly.

ASAP also increased sleeving in the

leading edge and replaced cable bracing

with tubing. Subsequent to these

changes, the design was subjected to

full static loading, with independent

analysis offered by a local university.

As proof of the design's longevity,

Brent reports that one Beaver RX550

has accumulated more than 2,000

hours while on duty in South Africa.

Those who own older RX550s may

purchase a conversion kit to upgrade

the earlier models.

Build time for the RX550 kit is estimated

by ASAP as 150 to 180 hours.

The builder simply assembles the kit,

no component fabrication is necessary,

and part accuracy is good-

thanks to the company's computercontrolled

machining.

ASAP also supports a wide selection

of engines for the RX550. Builders can

choose a Rotax 582 or 912, but ASAP

also works closely with HPower Ltd.,

in fitting the HKS 700E four-stroke

engine on the Beaver airframe.

The control system of the Beaver

RX550 Plus is quite conventional, using

pushrods to control ailerons, and

cables to effect rudder movements. It

has full-span ailerons, which Brent

says improves the handling significantly

on the RX550 Plus over the

original version. The RX550 Plus does

not have flaps, flaperons, or other

glide path control devices, though

ASAP indicated these devices might

be added in the future. Nor does it

have trim; however, an inventive kit

builder could create a trim system.

The Beaver RX550 Plus does have

the ultralight-like nose cone and

windscreen, but it opens to the sides,

giving open-air enthusiasts a machine

they'll enjoy.

A Single-Seater

Both the Chinook Plus and RX550

Plus are two-place machines. With

the ultralight exemption in the United

States expiring on January 31,

American owners of these two-place

machines will need to convert their

aircraft to experimental light-sport

aircraft (E-LSA) or experimental amateur-

built status to remain legal, while

our Canadian friends may continue

to fly these machines under Canada's

ultralight regulations.

ASAP has now introduced a singleseat

version of the Beaver. This recent

offering brings a pleasantly light

version of the former RX35 model

powered by a 40-hp Rotax 447 for

$17,500. At a typical empty weight

of 340 pounds, the Beaver SS doesn't

qualify as a Part 103 ultralight here

in the United States, but it does meet

Canada's rules and offers 300 pounds

of useful load. Americans who relish

single-seat aircraft could build this

machine as an amateur-built aircraft

and fly it as a sport pilot.

ASAP also increased sleeving in the

leading edge and replaced cable bracing

with tubing. Subsequent to these

changes, the design was subjected to

full static loading, with independent

analysis offered by a local university.

As proof of the design's longevity,

Brent reports that one Beaver RX550

has accumulated more than 2,000

hours while on duty in South Africa.

Those who own older RX550s may

purchase a conversion kit to upgrade

the earlier models.

Build time for the RX550 kit is estimated

by ASAP as 150 to 180 hours.

The builder simply assembles the kit,

no component fabrication is necessary,

and part accuracy is good-

thanks to the company's computercontrolled

machining.

ASAP also supports a wide selection

of engines for the RX550. Builders can

choose a Rotax 582 or 912, but ASAP

also works closely with HPower Ltd.,

in fitting the HKS 700E four-stroke

engine on the Beaver airframe.

The control system of the Beaver

RX550 Plus is quite conventional, using

pushrods to control ailerons, and

cables to effect rudder movements. It

has full-span ailerons, which Brent

says improves the handling significantly

on the RX550 Plus over the

original version. The RX550 Plus does

not have flaps, flaperons, or other

glide path control devices, though

ASAP indicated these devices might

be added in the future. Nor does it

have trim; however, an inventive kit

builder could create a trim system.

The Beaver RX550 Plus does have

the ultralight-like nose cone and

windscreen, but it opens to the sides,

giving open-air enthusiasts a machine

they'll enjoy.

A Single-Seater

Both the Chinook Plus and RX550

Plus are two-place machines. With

the ultralight exemption in the United

States expiring on January 31,

American owners of these two-place

machines will need to convert their

aircraft to experimental light-sport

aircraft (E-LSA) or experimental amateur-

built status to remain legal, while

our Canadian friends may continue

to fly these machines under Canada's

ultralight regulations.

ASAP has now introduced a singleseat

version of the Beaver. This recent

offering brings a pleasantly light

version of the former RX35 model

powered by a 40-hp Rotax 447 for

$17,500. At a typical empty weight

of 340 pounds, the Beaver SS doesn't

qualify as a Part 103 ultralight here

in the United States, but it does meet

Canada's rules and offers 300 pounds

of useful load. Americans who relish

single-seat aircraft could build this

machine as an amateur-built aircraft

and fly it as a sport pilot.

The wide open cabin is surrounded by well supported clear Lexan giving you a panoramic view from either seat. Tandem aircraft often cramp the aft seat and don't give it the best visibility, but Chinook sets a new standard. Your passenger or student will also enjoy plenty of room; a set of dual controls means the Chinook can easily be used for training flight.

After the ASAP company took over production they made numerous refinements that earn the name Chinook Plus 2, and those who have seen the older, simpler Chinooks need to reexamine the current model.

Flight characteristics of the old Chinook were largely preserved as the machine made the transition from simple single seater to the feature laden two seaters of today. A versatile design, Chinook endures for many good reasons.

The wide open cabin is surrounded by well supported clear Lexan giving you a panoramic view from either seat. Tandem aircraft often cramp the aft seat and don't give it the best visibility, but Chinook sets a new standard. Your passenger or student will also enjoy plenty of room; a set of dual controls means the Chinook can easily be used for training flight.

After the ASAP company took over production they made numerous refinements that earn the name Chinook Plus 2, and those who have seen the older, simpler Chinooks need to reexamine the current model.

Flight characteristics of the old Chinook were largely preserved as the machine made the transition from simple single seater to the feature laden two seaters of today. A versatile design, Chinook endures for many good reasons.

Over the years, ASAP's business has expanded and the western Canada company now sells the Chinook Plus 2 and the Beaver RX-550 Plus, tagging both models with the "plus" suffix that indicates the ASAP team improved and refined the aircraft after their acquisition of the models.

I find it impressive that two of Canada's most popular ultralights are now built by ASAP, a company that rescued these designs after the original companies failed. Birdman Enterprises designed and built the Chinook, and Spectrum Aircraft built the Beaver RX-550 (though the latter company went through a few name/ownership changes before succumbing completely).

Over the years, ASAP's business has expanded and the western Canada company now sells the Chinook Plus 2 and the Beaver RX-550 Plus, tagging both models with the "plus" suffix that indicates the ASAP team improved and refined the aircraft after their acquisition of the models.

I find it impressive that two of Canada's most popular ultralights are now built by ASAP, a company that rescued these designs after the original companies failed. Birdman Enterprises designed and built the Chinook, and Spectrum Aircraft built the Beaver RX-550 (though the latter company went through a few name/ownership changes before succumbing completely).

With some 700 Chinooks flying and at least 2,000 Beavers delivered, Canadians in particular and ultralight/microlight enthusiasts everywhere should rejoice that ASAP and the Holomis family has chosen to support these two design success stories.

Today, Brent and crew have logged 10 years as producer of the Chinook. I was pleased to fly the machine, and to update your understanding and awareness of this nice-flying Canadian ultralight.

With some 700 Chinooks flying and at least 2,000 Beavers delivered, Canadians in particular and ultralight/microlight enthusiasts everywhere should rejoice that ASAP and the Holomis family has chosen to support these two design success stories.

Today, Brent and crew have logged 10 years as producer of the Chinook. I was pleased to fly the machine, and to update your understanding and awareness of this nice-flying Canadian ultralight.

If you walk around the front of the design and sight down the nose toward the tail, you can see how the fairing got so wide when the design became fully-enclosed years ago. The landing gear struts extend up to the leading edge at the wing's center. Since the enclosure goes around these struts, the cockpit is made very broad.

Putting your bottom in the seat means lifting yourself over 6 or so inches of cockpit to the side of the seat. However, once you swing into position, you'll love the roominess. Even with a rear seat passenger's feet on rudder pedals right alongside your seat, space is plentiful. If you're a wide pilot, this machine might be your dream.

In the cockpit are the following controls: Center-mounted joystick with hydraulic brake lever on the front side. To your left and behind you somewhat you'll find a single throttle with two handles, one extended forward and one aft.

If you walk around the front of the design and sight down the nose toward the tail, you can see how the fairing got so wide when the design became fully-enclosed years ago. The landing gear struts extend up to the leading edge at the wing's center. Since the enclosure goes around these struts, the cockpit is made very broad.

Putting your bottom in the seat means lifting yourself over 6 or so inches of cockpit to the side of the seat. However, once you swing into position, you'll love the roominess. Even with a rear seat passenger's feet on rudder pedals right alongside your seat, space is plentiful. If you're a wide pilot, this machine might be your dream.

In the cockpit are the following controls: Center-mounted joystick with hydraulic brake lever on the front side. To your left and behind you somewhat you'll find a single throttle with two handles, one extended forward and one aft.

To me, the throttle idea seems taking simplicity too far. Dual throttle positions don't add that much weight or complexity but might be much more convenient. In the Chinook system, both pilots must reach somewhat awkwardly. I think such an important control needs to be more accessible. As I flew from the front, I had to feel around in back and to the side - somewhat like reaching for my wallet - to find the throttle. Maintaining a hand on the throttle, as is standard practice for most pilots, means holding your arm somewhat awkwardly behind you.

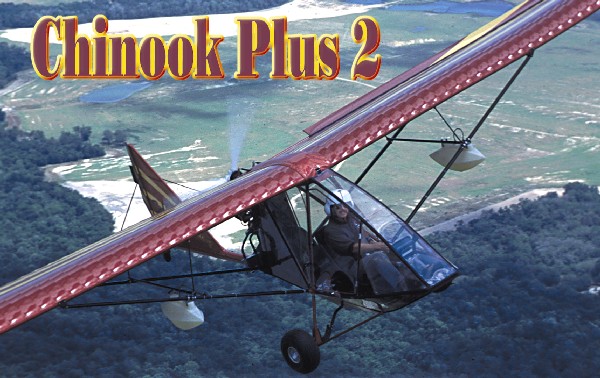

On the right side of the Chinook cabin is a control panel. It held the ignition switches, master switch, starter, primer and optional prop control lever. In front of the front-seat pilot, ASAP had installed the MaxPak instrument deck with its full complement of gauges. The electronic panel switches from cylinder to cylinder (on CHT or EGT) and offers other control by switch. It was the easiest-to-read instrument deck I've ever used. Below the MaxPak, ASAP had installed a few more temperature and pressure gauges to monitor the new 60-hp HKS 700E 4-cycle engine.

To me, the throttle idea seems taking simplicity too far. Dual throttle positions don't add that much weight or complexity but might be much more convenient. In the Chinook system, both pilots must reach somewhat awkwardly. I think such an important control needs to be more accessible. As I flew from the front, I had to feel around in back and to the side - somewhat like reaching for my wallet - to find the throttle. Maintaining a hand on the throttle, as is standard practice for most pilots, means holding your arm somewhat awkwardly behind you.

On the right side of the Chinook cabin is a control panel. It held the ignition switches, master switch, starter, primer and optional prop control lever. In front of the front-seat pilot, ASAP had installed the MaxPak instrument deck with its full complement of gauges. The electronic panel switches from cylinder to cylinder (on CHT or EGT) and offers other control by switch. It was the easiest-to-read instrument deck I've ever used. Below the MaxPak, ASAP had installed a few more temperature and pressure gauges to monitor the new 60-hp HKS 700E 4-cycle engine.

As you turn to secure the door with ASAP's little bungee cord fastener - which worked quite effectively - you can't help but notice the massive amount of clear area surrounding you. The visibility from the front seat of the Chinook is simply huge, even before you leave the ground. Noting how slick and clear their windscreen and enclosure appeared, Brent Holomis confided, "Lemon Pledge® is the secret." Certainly, it was easy on the eye.

As you turn to secure the door with ASAP's little bungee cord fastener - which worked quite effectively - you can't help but notice the massive amount of clear area surrounding you. The visibility from the front seat of the Chinook is simply huge, even before you leave the ground. Noting how slick and clear their windscreen and enclosure appeared, Brent Holomis confided, "Lemon Pledge® is the secret." Certainly, it was easy on the eye.

If it means something to Harley today, perhaps it will one day mean something to HPower (the U.S. importer) and HKS, because the newest 4-stroke aircraft engine certainly has its own sound. Amid a setting of 2-stroke-powered ultralights, the 700E is unmistakable, even compared to other 4-stroke engines.

I'd been told (in all HKS installations) to watch for oil temperatures higher than 200° - it never came close, typically running under 180° in the Chinook - and for adequate oil pressure. The HKS seemed hardly to be working to fly me and the Chinook around. I imagine it would do nearly as well even loaded with two large pilots.

ASAP builders did a great job of fitting the HKS, nestled as it is behind the rear cabin bulkhead. Lowering the engine below the upper wing trailing edge assures the upper surface stays uncluttered and efficient. It also gave the Chinook smooth lines visually.

As with other new installers of the HKS, Holomis had to experiment with the right position for the oil cooler radiator. It's a little thing, but it needs adequate airflow. The smooth exterior of the Chinook enclosure forced ASAP to move the cooler around, seeking the right spot.

If it means something to Harley today, perhaps it will one day mean something to HPower (the U.S. importer) and HKS, because the newest 4-stroke aircraft engine certainly has its own sound. Amid a setting of 2-stroke-powered ultralights, the 700E is unmistakable, even compared to other 4-stroke engines.

I'd been told (in all HKS installations) to watch for oil temperatures higher than 200° - it never came close, typically running under 180° in the Chinook - and for adequate oil pressure. The HKS seemed hardly to be working to fly me and the Chinook around. I imagine it would do nearly as well even loaded with two large pilots.

ASAP builders did a great job of fitting the HKS, nestled as it is behind the rear cabin bulkhead. Lowering the engine below the upper wing trailing edge assures the upper surface stays uncluttered and efficient. It also gave the Chinook smooth lines visually.

As with other new installers of the HKS, Holomis had to experiment with the right position for the oil cooler radiator. It's a little thing, but it needs adequate airflow. The smooth exterior of the Chinook enclosure forced ASAP to move the cooler around, seeking the right spot.

Brent Holomis expressed a lot of satisfaction with the HKS engine and spoke highly of his dealings with HPower personnel. Also like other new installers, he sees a market for HKS-powered Chinooks among pilots who prefer 4-stroke engines. It certainly seems appropriate for many 2-seat ultralight designs at its rated 60 horsepower.

Finally, Holomis mentioned the smooth torque power through a wide operating range and the very low fuel usage. Some users report as low as 2.0 gallons per hour, though 3.0 or so is more common. Regardless, this is less than a Rotax 503 doing the same work, and far less than a Rotax 582.

Brent Holomis expressed a lot of satisfaction with the HKS engine and spoke highly of his dealings with HPower personnel. Also like other new installers, he sees a market for HKS-powered Chinooks among pilots who prefer 4-stroke engines. It certainly seems appropriate for many 2-seat ultralight designs at its rated 60 horsepower.

Finally, Holomis mentioned the smooth torque power through a wide operating range and the very low fuel usage. Some users report as low as 2.0 gallons per hour, though 3.0 or so is more common. Regardless, this is less than a Rotax 503 doing the same work, and far less than a Rotax 582.

Takeoff and landing operations in the Chinook were extraordinarily easy. Every variation of speed, approach angles or descent technique I attempted made me look good. One reason this is so relates to the huge vision you have from the front seat. I never flew from the rear, but I'm sure it would be much compromised compared to the nose seat.

Another reason for the easy landings is the good roll control the Chinook shows. And it doesn't hurt that the large enclosure provides for excellent slip potential. For this reason, flaps aren't necessary to someone with a good slip technique.

Climb was strong thanks to the high-torque HKS engine. It isn't so much the rate of the climb with the 4-stroke engine; it's the way the 700E bears the load of a high-angled prop. Most 2-strokes express a sound of laboring when you nose-up steeply and climb for a sustained time. The HKS kept pushing us aloft without the slightest protest.

Takeoff and landing operations in the Chinook were extraordinarily easy. Every variation of speed, approach angles or descent technique I attempted made me look good. One reason this is so relates to the huge vision you have from the front seat. I never flew from the rear, but I'm sure it would be much compromised compared to the nose seat.

Another reason for the easy landings is the good roll control the Chinook shows. And it doesn't hurt that the large enclosure provides for excellent slip potential. For this reason, flaps aren't necessary to someone with a good slip technique.

Climb was strong thanks to the high-torque HKS engine. It isn't so much the rate of the climb with the 4-stroke engine; it's the way the 700E bears the load of a high-angled prop. Most 2-strokes express a sound of laboring when you nose-up steeply and climb for a sustained time. The HKS kept pushing us aloft without the slightest protest.

One thing you are always sure about in the Chinook is the fuel quantity. I have heard a few detractors say that airplanes shouldn't carry their fuel dangling from a wing strut. Fuel lines also must route a good distance and do so through the cabin (via a fuel control valve).

However, several hundred Chinooks have been operating this way for years without publicized problems. With the Chinook fuel tanks kept well away from the pilot, an incident may be less of a hazard thanks to this design.

No matter what else, anyone has to agree that seeing your remaining fuel couldn't get much easier. The Chinook's fuel cells are shapely to reduce drag.

Not much other space exists in the fuselage to put fuel (assuming that's where you believe it should be). And despite the cockpit's broad space, the Chinook provides no cargo room - unless that's how you use the back seat.

One thing you are always sure about in the Chinook is the fuel quantity. I have heard a few detractors say that airplanes shouldn't carry their fuel dangling from a wing strut. Fuel lines also must route a good distance and do so through the cabin (via a fuel control valve).

However, several hundred Chinooks have been operating this way for years without publicized problems. With the Chinook fuel tanks kept well away from the pilot, an incident may be less of a hazard thanks to this design.

No matter what else, anyone has to agree that seeing your remaining fuel couldn't get much easier. The Chinook's fuel cells are shapely to reduce drag.

Not much other space exists in the fuselage to put fuel (assuming that's where you believe it should be). And despite the cockpit's broad space, the Chinook provides no cargo room - unless that's how you use the back seat.

While I liked flying the Chinook a great deal, the rear seat didn't interest me much. The rear occupant's head is mere inches away from the engine. While it appears stoutly braced and I know of no problems related to this close engine, I should think noise and vibration might be offensive. Entry requires twisting around the strut placement. However, I didn't fly in the rear and I make no condemnation of the design. Since most pilots probably use the rear seat for stuff they want to bring aloft, the whole point may often be moot.

While I liked flying the Chinook a great deal, the rear seat didn't interest me much. The rear occupant's head is mere inches away from the engine. While it appears stoutly braced and I know of no problems related to this close engine, I should think noise and vibration might be offensive. Entry requires twisting around the strut placement. However, I didn't fly in the rear and I make no condemnation of the design. Since most pilots probably use the rear seat for stuff they want to bring aloft, the whole point may often be moot.

The Chinook can run to about 90 mph with the HKS engine on it. High cruise appeared to be in the range of 75 to 80 mph and an economical cruise brought her down to about 60 to 65. At the latter power setting and flown solo with a little baggage and full fuel, my guess is the HKS might burn only a couple gallons an hour. This would yield an endurance of close to 5 hours with standard wing strut tanks. Even flown at gross weight, you'll probably still get more than 3 hours aloft.

Stalls came in at 35 to 40 mph, usually hovering toward the low end of that range as I flew it. In all cases, stalls were mild and uneventful. With full power, the Chinook simply keeps climbing even with full backstick. The nose wanders a bit in this position, but not frighteningly so. Power-off stalls were very mild, as well, breaking but only subtly. I actually prefer a cleaner break so I know it happened, but I don't see pilots getting into any trouble with the Chinook. I can guess that stalls at gross might climb close to 40 mph, but the characteristics should stay similar.

The Chinook can run to about 90 mph with the HKS engine on it. High cruise appeared to be in the range of 75 to 80 mph and an economical cruise brought her down to about 60 to 65. At the latter power setting and flown solo with a little baggage and full fuel, my guess is the HKS might burn only a couple gallons an hour. This would yield an endurance of close to 5 hours with standard wing strut tanks. Even flown at gross weight, you'll probably still get more than 3 hours aloft.

Stalls came in at 35 to 40 mph, usually hovering toward the low end of that range as I flew it. In all cases, stalls were mild and uneventful. With full power, the Chinook simply keeps climbing even with full backstick. The nose wanders a bit in this position, but not frighteningly so. Power-off stalls were very mild, as well, breaking but only subtly. I actually prefer a cleaner break so I know it happened, but I don't see pilots getting into any trouble with the Chinook. I can guess that stalls at gross might climb close to 40 mph, but the characteristics should stay similar.

One surprising performance fact is the low sink rate of the Chinook. This wing design has impressed me before and a descent rate near 350 feet per minute beats virtually every other ultralight 2-seater I've flown. Glide didn't seem quite as strong, and yet the two parameters are somewhat linked. I can't explain, but feel confident the sink rate is superior. This is good to know if you must ever glide to a landing.

Two lone complaints in the safety arena are: (1) no standard shoulder belts (they're optional) and (2) no parachute was fitted (also optional). I'd sure like it better when flying new ultralights if manufacturers would install them.

One surprising performance fact is the low sink rate of the Chinook. This wing design has impressed me before and a descent rate near 350 feet per minute beats virtually every other ultralight 2-seater I've flown. Glide didn't seem quite as strong, and yet the two parameters are somewhat linked. I can't explain, but feel confident the sink rate is superior. This is good to know if you must ever glide to a landing.

Two lone complaints in the safety arena are: (1) no standard shoulder belts (they're optional) and (2) no parachute was fitted (also optional). I'd sure like it better when flying new ultralights if manufacturers would install them.