I was inspired to write this article by a comment made on a previous article I wrote on MOSAIC. I had indicated that MOSAIC had the potential to bring new aircraft to market at half the price of current legacy offerings. The commenter made the point that even at half the price, this would still not make it inherently “affordable” to most people.

This topic will be covered in two articles. The first will discuss how shared ownership is able to bring down the costs of accessing an airplane and thus, making it potentially more affordable to a wider pilot demographic. The second article will detail two proposals on how some form of shared ownership could be expanded into a regional or national model.

How the Numbers Add Up

Affordability is really not a single quantifiable number that can be used to judge a product. There are simply too many other factors such as income, lifestyle and geographical location that have to be taken into account while, of course, no two people see their life priorities the same way. How that product is accessed will also have a significant effect on its affordability. The simplest examples being the purchase of a house or a new car. If they all had to be paid for in cash, there would be very limited home or car ownership. In these examples, the ability to spread the purchase cost over an extended period of time makes an unaffordable/inaccessible item affordable. To some extent this would be true for a plane but, for most people, a house or car are considered essential while a plane is typically seen as a luxury so access to loans to buy them are somewhat restricted and expensive due to the relatively small market.

Trying to determine what it costs for an average person to own a plane is challenging for a number of reasons including the value of the plane, where it is located, the financial situation of the owner and how many hours it will actually be flown in a year.

The FAA produces an annual general aviation survey, the most recent one being for 2022. Using the total number of hours flown and categorized as “personal” (8.2 million hours) divided by the number of planes categorized as “personal” (141,600) we get a figure of just under 58 hours per year per plane. Personal planes and hours include rotorcraft and fixed wing single and multi-engine. Another part of the survey indicates single engine piston planes fly less hours per year on average than both multi engine planes and rotorcraft, so the 58 hours average is probably an overstatement, but we will use it here for convenience.

What About Costs?

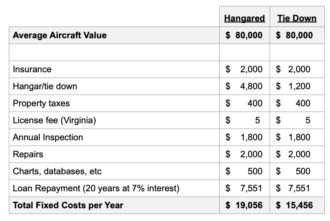

Table 1

Here, we really have to make some assumptions, so these are mine based on 34 years of ownership, operation, aircraft management, from multiple FBOs and flight schools in Virginia and Florida.

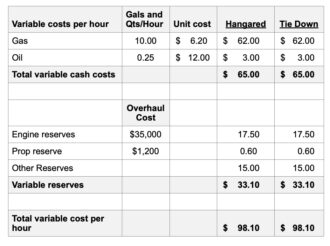

Two types of cost are used when creating a forecast, fixed and variable. A fixed cost is one that is not usually going to change irrespective of the hours flown, a good example being insurance. A variable cost is one that is going to apply to every hour flown, a good example being fuel. Some variable costs cover future expenses such as an engine overhaul and are not cash being spent every year but is money you have to put to one side to save up for the eventual expense. These are called reserves. Aircraft ownership comes with a very heavy dose of fixed costs. Total annual cost of ownership is the addition of fixed plus variable costs. The cost per hour of flight is the total annual cost divided by the hours flown.

Table 2

In our example we are going to look at a plane that cost $80,000, was purchased with a 20 year loan at 7% annual interest. The detailed numbers are in three tables at the end of the article. I will just provide a simple summary here, so as to maintain simplicity.

In our example:

Fixed costs per year (Table 1): $19,056 (hangared) or $15,456 (tied down)

Variable cost per hour (Table 2): $98.10 ($65.00 Cash and $33.10 reserves)

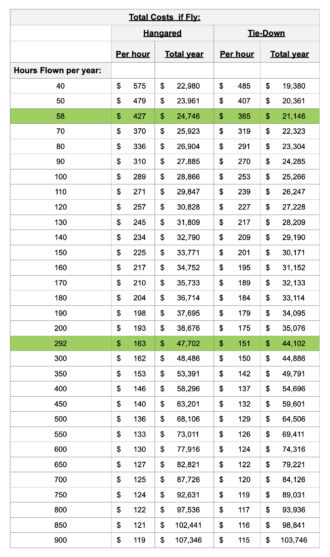

At the “average” flight hours of 58 per year, this comes to $427 per hour (hangared) and $365 Per hour (tied down). Both being significantly higher than if a similar plane was being rented from the local airport.

Table 3

However, where the magic starts is as the total numbers of hours per year start to increase (Table 3):

This table highlights some key information:

- Five people owning the plane with each one using it for about 58 hours (292 hours) reduces the cost per hour by $264 (hangared) and $214 (tied down).

- Fly 900 hours per year and the cost per hour falls to $119 (hangared) and $115 (tied down).

- At 58 hours per year the recovery of fixed costs comes to $329 per hour (Hangared) and $266 (tied down).

- At 292 hours the fixed costs make up $65 (hangared) $53 (tied down).

- At 900 hours the fixed costs make up $21 (hangared) and $17 (tied down).

- As the number of hours increases the differential between keeping the plane hangared and tied down reduces dramatically.

- The rate of decrease in cost per hour slows down considerably as the total hours increase suggesting an optimum number of hours per year.

- The clear lesson here is that higher volumes have the potential to turn an unaffordable luxury into something significantly more accessible and affordable. Consequently, when you look at these figures it is difficult to see why people would actually want to own any aircraft rather than rent, as all but the most frugal would save money. This also explains why the main cost saving model people have adopted is that of shared ownership through partnerships, flying clubs and managed ownership.

Typical responses given to this question might include:

- The rental aircraft are just not available when I want to fly

- I can’t go off on a long trip in a rental plane

- They are not kept in good enough condition

- Always down for some reason or another’

- Too expensive

- Does not have the type I like to fly

- I like the freedom of making a spur of the moment decision

- Planes get too much use, don’t trust the maintenance

- Not enough of the model I like to fly

- I never share anything

- There are surely many more.

Some Typical Forms of Shared Ownership

Each of these solutions brings with it a different set of constraints. The biggest issues with partnerships come down to personality and attitude conflicts. It is very difficult to ensure that you get the right blend of people together who have shared values – anything broken will be fixed, aircraft will be kept clean with fuel after every trip etc. That is without even touching on the challenges of everybody wanting to fly at the same time and what happens when the plane is down for an extended annual, upgrades or repair.

Flying clubs can bring more discipline to the whole concept of shared ownership/Shared use and even add the attraction of multiple aircraft but, with a multiplication of shared owners/users the potential for conflicts also multiply. There are some great examples of flying clubs that have been around for many decades. These tend to have more formal rules than partnerships but are usually set up as not for profit and are run by volunteers with a common interest so the ongoing quality of the experience can be highly variable over time.

Professionally managed ownership got a significant boost about 18 years ago spurred on by the excitement generated by Cirrus which led to a number of fractional ownership programs being created and sold. However, these were being created as a way to sell more Cirrus aircraft and promoted by people looking to make very substantial profits from the programs. They ultimately failed because they did not really aim to bring costs down for the owners through volume and there were too few customers looking for such a high-end experience. Nevertheless, the concept did take off it many different forms for turbine aircraft where the costs of professional management are not a major obstacle to the high net worth individuals and companies who are customers as their alternatives could be even higher cost charter or sole ownership.

Ultimately, the key takeaway from all of this is that volume is what brings down costs and makes aviation more affordable but, it does not necessarily address the challenges of accessibility. Accessibility only comes from there being a plentiful supply of aircraft, and organization to put the aircraft where the demand is.

MOSAIC, the subject of a prior article that I wrote, has the potential to offer aircraft with much lower variable operating costs than legacy aircraft but, with potentially higher fixed costs as they would be newer and likely much better equipped. With high volumes bringing down the fixed costs per hour plus lower variable costs, the overall economics could well place new aircraft within the reach of many more people.

The second article in this series will cover some of the potential solutions to accessibility to shared ownership/usage aircraft.

I would agree with all of the above. I have assisted many people over the years and conducted co-ownership workshops for the EAA and AOPA years ago. In summary the recreational partnerships that are successful are the ones that have made an effort towards determining partner compatibility. I would suggest, whether forming a partnership or bringing in a new partner, determine in the partners have more in common then just flying. Do they share the same civic groups, church activities, other hobbies or political persuasion? Have the wives and children get together for a luncheon or picnic. If the spouses and kids get along with each other chances are the A/C partners will to.

Partnerships that will have conflict and a short lifespan: Mixing business flying with recreational flying, some one with a strong emotional attachment and selling shares to afford “his’ airplane, all shares are equal; no I own 51% and you own 49%; mixing student pilot owners with high time owners. And the list can go on. Lot’s of other areas of conflict, but they can be addressed with the right up front questions, courtesy, and humility. Not everyone is cut out to be a co-owner. My book covers all these topics and more: Keeping the Peace in Partnerships; A Guide to A/C Co-ownership. Available on my website. Dan- Thanks for letting me share!