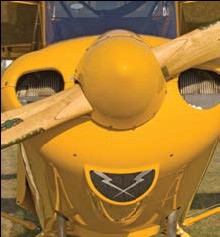

Power for the Sport Cub is a 100-hp Continental

O-200 engine, with either a Sensenich wood propeller

or optional McCauley metal prop|appropriate

for those folks planning to put the Sport

Cub on floats.

The Sport Cub has a traditional bungee cord suspension system, but it’s dressed up a bit with covers to keep dirt and debris out.

The “office” of the Sport Cub

features a traditional side throttle along with fuel selector switch. While this particular Sport Cub is equipped with an optional full glass panel, CubCrafter’s

offers a more traditional panel. To accommodate folks of Jim Richmond’s height, the Sport Cub’s cockpit is 30 inches wide and 52 high.

The back seat in the Sport Cub has a hammock-style back that can be rolled up and stored like header …

Jim Richmond demonstrates the technique.

… resulting

in a large storage area that can hold up to 100 pounds of cargo (if within weight and balance limitations).

CubCrafters Debuts ‘Carbon Cub’

Proof Of Concept

The S-LSA Useful Load Requirement

Vintage Looks Mated With Modern Materials

Take 25 years of experience

with rebuilding Piper Cubs,

add a new FAA regulation

allowing more flexibility in designing

and producing aircraft, spice the

mixture with many design changes,

and you get CubCrafters’ Sport Cub.

The Yakima, Washington-based company

has created an airplane that retains

the vintage look of a J-3 Cub

but embraces 21st century materials

and technology.

On a warm evening during

the Sun ‘n Fun Fly-In

at Lakeland, Florida, I

flew with CubCrafters’

pilot Clay Hammond. He

identified company President

Jim Richmond as the primary

motivator behind the Sport Cub.

Richmond has been rebuilding Cubs

for 25 years, during which time he

conceived many changes he wanted

to try. Taking into consideration his

height-he’s 6 feet 4 inches tall-he

wanted to make all the improvements

he’d envisioned for the venerable

Cub, and he wanted the airplane

to fit him.

A Thoroughly Modern Cub

CubCrafters took on the redesign

of the 50-year-old airplane using

modern materials and engineering

software not available to Piper engineers

when the J-3 was created. The

result is a stronger, lighter weight

fuselage structure. CubCrafters Vice

President Todd Simmons said the

company made extraordinary efforts

to lighten the Sport Cub’s airframe

to stay within the maximum

gross weight allowed for light-sport

aircraft (LSA)-that’s 1,320 pounds

for landplanes and 1,420 pounds for

seaplanes. One example of this effort

is a cowling built of composite

materials instead of aluminum. Additionally,

the Sport Cub’s wingtips

have a carbon fiber component that

sweeps from a D-cell shape to a tubular

shape at the trailing edge.

The Sport Cub’s main fuselage

structure uses composite stringers for

shaping where cosmetic finish is the

goal. Wherever structural strength is

important, CubCrafters uses steel or

aluminum.

In many places where a steel part

might be used, the Sport Cub uses a

machined aluminum billet fashioned

into a specialized part, according to

Clay. The effort was made in the interest

of saving ounces, but the parts

are beautiful. At the base of the Sport

Cub’s joystick are handsome aluminum

machined fittings that function

as ailerons linkages.

Overall, the Sport Cub exhibits excellent

finish work from the machined

parts to the beautiful paint job. Clay

attributed that to Richmond’s many

years of involvement with this airframe.

Poly-Fiber coverings and coatings

are used to the silver finish stage,

with PPG paint used for the attractive

final finish.

The Sport Cub manages to preserve

the image of an original Cub while delivering

an all-new design with significant

redesign work to address ASTM

standards. Retro automobiles like the

Thunderbird also hark back to the familiar

models of yesteryear yet add

new construction technology to the

mix. Appropriate to the Sport Cub’s

contemporary premise, the entire

plane was created with SolidWorks

engineering software.

The final evidence of CubCrafters’

work to shave weight wherever possible

is that Sport Cub number one,

N468CB, has an empty weight of

877 pounds according to the pilot’s

operating handbook in the airplane.

That weight would permit another 13

pounds of equipment and yet still be

within the ASTM standards requirement

that all S-LSA have a minimum

useful load of 430 pounds. Most original

Cubs had no electrical systems,

but the new millennia Sport Cub

does, to accommodate avionics and

a built-in landing light in the wing.

And it has two 12-gallon fuel tanks

located in the wings.

The Feel Is Real

Similar to authentic Piper J-3s, the

Sport Cub has no door on the left

side. In exchange for entry there’s a

broad window offering good lateral

vision and a somewhat aft view. The

windshield is also large as it extends

into a skylight, which adds lateral visibility

in turns.

Open-cockpit flying lovers can rejoice.

The Sport Cub’s windows and

door may be opened at any time during

flight. However, Clay indicated

that if you are “tached up” (that is,

the engine revving high), it gets

pretty windy inside. He sets power

at about 2100 rpm to have a better

open-cockpit flying experience. Why

fly with the windows open at the

highest speed the Sport Cub can muster,

especially considering how well it

slows down?

The Sport Cub’s floorboard is a

single piece of fiberglass that is built

into the airplane as it is assembled;

it lends a quality finish and coordinates

well with the handsome machined

parts.

The aft, hammock-style seat can be

folded up to effectively become part of

the headliner. Once it’s stowed properly,

the back area opens up for other

uses. The Sport Cub can be loaded

with 100 pounds in this aft area plus

another 20 pounds in the hat rack, assuming

the cargo is well secured and

remains within the weight and balance

envelope. This aft area’s versatility

adds value to those wishing to use

the Sport Cub as a bushplane.

To improve support when used by

a passenger, carbon-fiber pieces are

added to lend structure. A cushion

goes on top of the basic seat for additional

comfort.

Our test Sport Cub had a sturdylooking

Aircraft Spruce tail wheel.

However, bush pilots will want to

upgrade to the optional Scott tail

wheel, which puts more surface on

the ground. The Sport Cub’s landing

gear has a bungee cord suspension

like original Cubs, though the cords

are modernized with a fairing cover.

Slow-Flying Delight

Here’s my confession: I’m a longtime

ultralight pilot who appreciates the

ability to fly slowly over the landscape.

When I discovered the great slow-speed

qualities of the Sport Cub, I knew I’d

like it for low-and-slow flying.

On landing, we used one notch of

flaps and powered back substantially

abeam the landing point. We used 65

mph on base leg and 55 mph on approach.

These comfortably low numbers

are merely a baseline. Clay said when

flying solo, well under gross, he can

approach safely at 45 mph (39 knots),

which allows landings in small spaces.

The Sport Cub’s optional flaps have

a noticeable effect when you deploy

them. The first notch of flaps, normally

deployed at a higher airspeed,

caused a significant pitch change. To

best operate these flaps, you first relieve

the pressure on the flap handle

before deflecting the detent release

with your thumb. When adjusting to

a new setting, you first move the lever

slightly and then engage the detent

tab. Flap forces were light, making

this an easy adjustment.

Clay described a technique he uses if

he wishes to loiter in the pattern, perhaps

to allow traffic ahead more spacing.

He puts down full flaps and enters

slow flight, dropping the airplane to 28

mph while holding altitude. My own

test of this technique quickly gave reassurance

that it’s possible. The Sport

Cub slows down marvelously.

Despite a good bit of taildragger

experience, I bounced slightly on my

early landings. There was a brisk crosswind

at South Lakeland Airport during

my evaluation flight. In such conditions,

Clay likes to execute wheel

landings. Therefore, I did likewise,

though my usual method is the fullstall

landing on three points of a taildragger.

Clay’s technique is to come

in tail low and plant the mains fairly

authoritatively. Once the mains are

on to stay, he eases the stick forward

to maintain this posture. I tried this

technique to achieve my best landing

of the bunch.

While taxiing, I was pleasantly

surprised to find that you can see

over the nose quite well despite the

taildragger deck angle, and the Sport

Cub’s brakes proved potent. You can

break loose the tail wheel to pivot on

the mains once your technique is sufficiently

practiced.

My Dutch roll coordination exercises

went well from the start. Over

the years, I’ve found this to be a reliable

way to judge overall control

authority, response, and harmony.

Many airplanes require a few hours

of experience to appreciate their

fine points; others come quickly,

and the Sport Cub is in the latter

group. However, I found the joystick

seemed a bit heavier in control motions

contrasted with the powerful

rudder pedals.

As cleanly executed as the joystick

hardware was, the stick became rather

slippery in my hand; I’d prefer a more

tactile grip. Fashioned out of an aluminum

tube, the diameter was thin

and thus difficult to hold.

Steep turns done at 2500 rpm

(about 75 percent power) required

no additional power to hold altitude,

and I did not have to change trim to

sustain the turn. In the steep turn

without a trim adjustment, I found a

fair amount of stick backpressure was

required, but I was easily able to hold

the turn to within 100 feet of deviation

through two full circles. This was

true in either direction.

Stalls in all simulations worked

without surprise. Given the Sport

Cub’s wonderful low-speed capability,

I expected stalls would be docile,

and they were. My longitudinal stability

check went equally uneventful

as well. The same can be said for power

response checks with no sustained

oscillation before the Sport Cub responded

in the correct direction.

At 2450 rpm, approximately 65

percent power, I saw about 88 mph

(76 knots) on the airspeed indicator.

At this power setting Clay believed

fuel consumption would be about 5

gph. Bumping power to 75 percent

would raise the burn rate to 5.5 gph,

he thought, and speed climbed into

the low 90s.

In a timed descent checked through

120 seconds, I saw a sink rate of about

420 fpm. With the engine idling and

producing plenty of drag, this qualifies

as excellent in the LSA category.

Later in the day, with conditions mellowing,

the vertical speed indicator

confirmed this idle-power sink rate.

As you look over the Sport Cub,

you’ll notice vortex generators on the

wings’ upper surface. They contribute

to its slow speed flying capability

but set the CubCrafters’ version apart

from other LSA Cubs in one more way.

Though Cubs are known for their highlift

wing, the generators do a good job.

On his departure to the Plant City

airport, Clay demonstrated a short

takeoff roll in the Sport Cub flown

solo after the heat of the day passed.

I estimate he was off in less than 150

feet. I also noticed that the Continental

engine is considerably noisier than

a Rotax lifting a similar weight.

Top-of-The-Line Cub

The Sport Cub is nicely finished,

but that heightened level of professionalism

comes at a price premium.

The base price of the Sport Cub is

listed at $99,500 in spring 2007. But

that doesn’t include the flaps I used

($6,500), the twin fuel tanks (12 gallons

is standard; 24 gallons will cost

$1,700), or all the panel goodies.

Nonetheless, a base-price Sport Cub

is a well-equipped machine. On the

panel you get an airspeed indicator, altimeter,

compass, tachometer, oil temperature

gauge, oil pressure gauge, inclinometer,

and Garmin SL40 VHF communications

transceiver. If you want

GPS and glass instrumentation, you

can spend $10,000 to $20,000 more.

An intercom adds another $1,000. If

you want colors other than the “standard

Cub” look, optional paint adds

$2,900, and the obligatory emergency

locator transmitter adds $1,100.

The Sport Cub I tested would approach

$130,000 in price. But for this

premium, you get an airplane essentially

built in a Part 23 environment,

the same as used by Cessna, Cirrus,

and Diamond. You also get an airplane

that complies with the ASTM

useful load requirement. In fact, Cub-

Crafters “prices” the Sport Cub in

dollars and pounds.

The ASTM standards for LSA call

out a minimum useful load of 430

pounds; that value subtracted from

the maximum gross weight of 1,320

pounds means no 100-hp two-seat SLSA

landplane can weigh more than

890 pounds empty. Buyers have a reasonable

duty to examine an S-LSA’s

weight and balance information to

assure any plane that interests them

actually meets ASTM guidelines.

With its base price equipment,

CubCrafters says the Sport Cub will

weigh only 825 pounds empty, as a

result of the company’s extensive effort

to keep weight down. With the

basic options I specified above, the

Sport Cub should weigh 856 pounds,

well under the 890-pound maximum.

This means if you simply must

have more options, CubCrafters has

planned well and worked hard to allow

you make your Sport Cub the

Cub you want.

Reflecting on the care and long experience

used by CubCrafters to create

its LSA, you realize not all Cubs are created

equal. If you are a particularly demanding

buyer, the Sport Cub should

make a great choice for you. Get informed

via the company’s website, and

then get a demo flight. A Sport Cub

might look good in your hangar.

| Seating | 2, tandem |

| Empty weight | 825 pounds |

| Gross weight | 1,320 pounds |

| Wingspan | 34.8 feet |

| Wing area | 176 square feet |

| Wing loading | 7.5 pounds/square foot |

| Length | 23.3 feet |

| Cabin Interior | 30 inches |

| Height | 8.4 feet (tail down) |

| Fuel Capacity | 12 gallons 1 |

| Baggage area | 130 pounds total 2 |

| Airworthiness | Certified SLSA |

| Notes: | 1 24-gallon optional capacity, two tanks 2 110 pounds behind copilot seat; 20 pounds in hat rack |

| Standard engine | Continental O-200 1 |

| Prop Diameter | two-blade wood, Sensenich 72×44 |

| Power | 100 hp at 2700 rpm |

| Power loading | 13.2 pounds/hp |

| Cruise speed | 91 knots/105 mph |

| Stall Speed (Flaps) | 31 knots/36 mph |

| Never exceed speed | 120 knots/138 mph |

| Rate of climb at gross | 800 fpm |

| Takeoff distance at gross | 250 feet |

| Landing distance at gross | 200 feet |

| Range (powered) | 550 miles, 6 hours (no reserve) |

| Fuel Consumption | about 4-5 gph 2 |

| Notes: | 1 Time between overhauls-1,800 hours 2 See article for more consumption info. |

Is Continental producing the 0-200? I thought that that engine was long gone. What pitch prop can you get? Anything close to a bore prop? Also float fittings. Thanks.! —George in Alaska.

By all means, contact Continental Aerospace and inquire.