What started as Canadian Ultralight Manufacturing has now become ASAP and Brent Holomis is now president again. In the early days of the Vernon, British Columbia company, Brent became occupied with GSC props and focused on building that enterprise while brother Curt dealt with aircraft sales. Now they’re both involved in aircraft manufacturing.

Expanding Enterprise

Over the years, ASAP’s business has expanded and the western Canada company now sells the Chinook Plus 2 and the Beaver RX-550 Plus, tagging both models with the “plus” suffix that indicates the ASAP team improved and refined the aircraft after their acquisition of the models.

Over the years, ASAP’s business has expanded and the western Canada company now sells the Chinook Plus 2 and the Beaver RX-550 Plus, tagging both models with the “plus” suffix that indicates the ASAP team improved and refined the aircraft after their acquisition of the models.

I find it impressive that two of Canada’s most popular ultralights are now built by ASAP, a company that rescued these designs after the original companies failed. Birdman Enterprises designed and built the Chinook, and Spectrum Aircraft built the Beaver RX-550 (though the latter company went through a few name/ownership changes before succumbing completely).

With some 700 Chinooks flying and at least 2,000 Beavers delivered, Canadians in particular and ultralight/microlight enthusiasts everywhere should rejoice that ASAP and the Holomis family has chosen to support these two design success stories.

With some 700 Chinooks flying and at least 2,000 Beavers delivered, Canadians in particular and ultralight/microlight enthusiasts everywhere should rejoice that ASAP and the Holomis family has chosen to support these two design success stories.

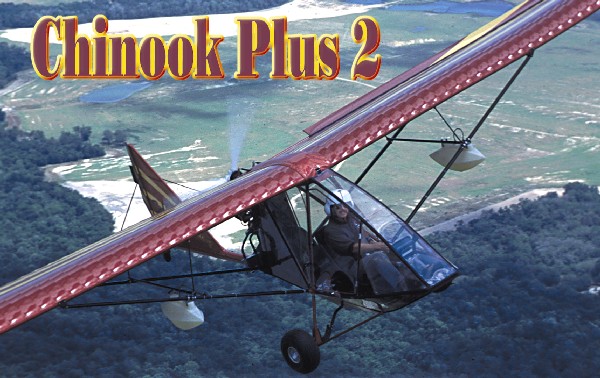

Today, Brent and crew have logged 10 years as producer of the Chinook. I was pleased to fly the machine, and to update your understanding and awareness of this nice-flying Canadian ultralight.

Unique Features

Though its wide basepan gives the Chinook a rather tubby look from some angles, the design slips through the air quite well. It recorded one of the lowest idle-thrust sink rates of any 2-seat ultralight I’ve flown. And the Chinook has light and powerful ailerons that make it a joy to fly.

If you walk around the front of the design and sight down the nose toward the tail, you can see how the fairing got so wide when the design became fully-enclosed years ago. The landing gear struts extend up to the leading edge at the wing’s center. Since the enclosure goes around these struts, the cockpit is made very broad.

If you walk around the front of the design and sight down the nose toward the tail, you can see how the fairing got so wide when the design became fully-enclosed years ago. The landing gear struts extend up to the leading edge at the wing’s center. Since the enclosure goes around these struts, the cockpit is made very broad.

Putting your bottom in the seat means lifting yourself over 6 or so inches of cockpit to the side of the seat. However, once you swing into position, you’ll love the roominess. Even with a rear seat passenger’s feet on rudder pedals right alongside your seat, space is plentiful. If you’re a wide pilot, this machine might be your dream.

In the cockpit are the following controls: Center-mounted joystick with hydraulic brake lever on the front side. To your left and behind you somewhat you’ll find a single throttle with two handles, one extended forward and one aft.

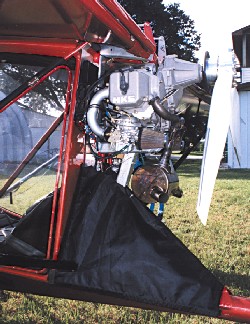

On the right side of the Chinook cabin is a control panel. It held the ignition switches, master switch, starter, primer and optional prop control lever. In front of the front-seat pilot, ASAP had installed the MaxPak instrument deck with its full complement of gauges. The electronic panel switches from cylinder to cylinder (on CHT or EGT) and offers other control by switch. It was the easiest-to-read instrument deck I’ve ever used. Below the MaxPak, ASAP had installed a few more temperature and pressure gauges to monitor the new 60-hp HKS 700E 4-cycle engine.

Purring Along

The electric-start HKS fired exactly as you’d expect a 4-stroke to do. It caught quickly and purred in readiness for taxi. Having flown several HKS-powered ultralights, the sound was no longer unusual to me, but it remained unique.

A lot has been said and written about the Harley-Davidson motorcycle’s sound, that “potato, potato” noise that so defines the big bike’s engine. In fact, to confront the invasion of sound-alike Japanese bikes, Harley is trying to copyright the distinctive noise!

I’d been told (in all HKS installations) to watch for oil temperatures higher than 200° – it never came close, typically running under 180° in the Chinook – and for adequate oil pressure. The HKS seemed hardly to be working to fly me and the Chinook around. I imagine it would do nearly as well even loaded with two large pilots.

ASAP builders did a great job of fitting the HKS, nestled as it is behind the rear cabin bulkhead. Lowering the engine below the upper wing trailing edge assures the upper surface stays uncluttered and efficient. It also gave the Chinook smooth lines visually.

As with other new installers of the HKS, Holomis had to experiment with the right position for the oil cooler radiator. It’s a little thing, but it needs adequate airflow. The smooth exterior of the Chinook enclosure forced ASAP to move the cooler around, seeking the right spot.

Finally, Holomis mentioned the smooth torque power through a wide operating range and the very low fuel usage. Some users report as low as 2.0 gallons per hour, though 3.0 or so is more common. Regardless, this is less than a Rotax 503 doing the same work, and far less than a Rotax 582.

Off We Go, Easily

Taxiing out on a breezy day, I appreciated the low and wide stance of the Chinook. You hardly feel like you’re operating a taildragger because the deck angle (fore to aft slope of the centerline of the fuselage) is modest. Most pilots will be happy to hear you can practically handle the Chinook as though it were a tri-gear design.

Another reason for the easy landings is the good roll control the Chinook shows. And it doesn’t hurt that the large enclosure provides for excellent slip potential. For this reason, flaps aren’t necessary to someone with a good slip technique.

Climb was strong thanks to the high-torque HKS engine. It isn’t so much the rate of the climb with the 4-stroke engine; it’s the way the 700E bears the load of a high-angled prop. Most 2-strokes express a sound of laboring when you nose-up steeply and climb for a sustained time. The HKS kept pushing us aloft without the slightest protest.

However, several hundred Chinooks have been operating this way for years without publicized problems. With the Chinook fuel tanks kept well away from the pilot, an incident may be less of a hazard thanks to this design.

No matter what else, anyone has to agree that seeing your remaining fuel couldn’t get much easier. The Chinook’s fuel cells are shapely to reduce drag.

Not much other space exists in the fuselage to put fuel (assuming that’s where you believe it should be). And despite the cockpit’s broad space, the Chinook provides no cargo room – unless that’s how you use the back seat.

What a Load Star

A 430-pound Chinook (empty, with the HKS engine) can carry a maximum of 950 pounds leaving 520 pounds of useful load. Subtract 60 pounds for fuel (10 gallons) and you are left with 460 pounds of payload, or two 230-pound occupants. That’s a lot of beef, and flown solo, your “cargo” could be quite significant. ASAP’s brochure depicts a Chinook with a 100-pound propane tank strapped in the aft seat – a trapper flies the load to his cabin in the bush.

Stalls came in at 35 to 40 mph, usually hovering toward the low end of that range as I flew it. In all cases, stalls were mild and uneventful. With full power, the Chinook simply keeps climbing even with full backstick. The nose wanders a bit in this position, but not frighteningly so. Power-off stalls were very mild, as well, breaking but only subtly. I actually prefer a cleaner break so I know it happened, but I don’t see pilots getting into any trouble with the Chinook. I can guess that stalls at gross might climb close to 40 mph, but the characteristics should stay similar.

Two lone complaints in the safety arena are: (1) no standard shoulder belts (they’re optional) and (2) no parachute was fitted (also optional). I’d sure like it better when flying new ultralights if manufacturers would install them.

Should You Purchase?

The Holomis brothers have an easy-going, low-key way about them. They’ve obviously shown determination by remaining in the ultralight business for a decade. And they demonstrated good strategy in capturing two of Canada’s top ultralight designs to build in their high-tech plant. Not bad for a couple of young Canadian businessmen and their families.

The Holomis family first developed a following in Canada by supplying parts for the Chinook and Beaver. Dealers lost their manufacturer support when previous companies failed, and were anxious for someone to help. Since they could make all the parts in-house using versatile CNC milling equipment, the family’s effort lead to supplying whole aircraft as well as parts for more than 3,000 Chinook and Beaver owners. As many companies as I’ve seen come and go in the 20 years of ultralight flying, I’m pleased to see an enterprise like

ASAP on the job

Now with a new U.S. distributor, ASAP can make a more determined push into the big American marketplace. Joplin Light Aircraft in Missouri will represent the Canadians under the direction of John and Amy Lukey.

Either of the Canadian ultralights the Lukeys have to sell you — the Chinook Plus 2 or the Beaver RX-550 Plus — could satisfy most pilots. However, for those with a taste for more refined handling, the Chinook has a clear edge. And its superwide fully-enclosed cabin will keep you comfortable in cooler weather and on longer flights.

Add the HKS engine to the Chinook airframe and you can have an impressive ultralight kit for $13,500. A price like that isn’t uncommon for any 2-seater with engine, but we’re talking a 4-stroke reputation here. The Chinook HKS is actually a good value in a fun flying machine.

| Seating | 2-seat, tandem |

| Empty weight | 430 pounds |

| Gross weight | 950 pounds |

| Wingspan | 32 feet |

| Wing area | 155 square feet |

| Wing loading | 6.1 pounds/sq ft |

| Length | 17 feet 8 inches |

| Height | 5 feet 10 inches |

| Load Limit | +4 Gs, -2 Gs |

| Kit type | Assembly |

| Build time | 150-180 hours |

| Standard engine | HKS 700E 4-cycle |

| Power | 60 hp at 5,900 rpm |

| Power loading | 15.8 pounds/hp |

| Cruise speed | 78 mph |

| Stall Speed | 33 mph |

| Never exceed speed | 115 mph |

| Rate of climb at gross | 800 feet per minute |

| Takeoff distance at gross | 200 feet |

| Landing distance at gross | 300 feet |

| Standard Features | Dual controls (shared left-hand throttle), steerable tailwheel, fully-enclosed cabin, removable doors, instrument panel, adjustable mechanical flaperons, dual fuel tanks (10-gallon U.S. capacity), seat belts, seat covers. |

| Options | Rotax 503 dual carb or 582, Hirth 2703, 2704 or 2706 or 2si 460F-45, 460L-50 or 690L-70 engine, standard or heavy-duty reduction drives, electric start, silencer kit, hydraulic disc brakes, electric flaperons, cabin heat, ballistic parachute, 5-point shoulder harnesses, floats, skis, instruments, 2- or 3-blade wood or composite props, custom interior. |

| Construction | Aluminum tubing airframe, bungee suspension, Ceconite® fabric covering; bolt-together kit – parts precut and predrilled, fabric precut. Made in Canada. |

Design

Cosmetic appearance, structural integrity, achievement of design goals, effectiveness of aerodynamics, ergonomics.

Pros – Now 10 years in production by ASAP, the Chinook is a reliable aircraft to buy and fly. More than 700 reportedly flying with a good record. Simple lines thanks to the original developer, yet with unusually generous interior room. Flight test model was nicely finished, outside and inside. Nice execution of HKS installation; nestles away cleanly.

Cons – Head-on the Chinook has a certain bathtub look to it (though it’s shape works well aloft). Some don’t care for wing strut fuel tanks so far from the engine (though this may have a safety aspect to it). Tandem seating isn’t for everyone.

Systems

Subsystems available to pilot such as: Flaps; Fuel sources; Electric start; In-air restart; Brakes; Engine controls; Navigations; Radio; (items covered may be optional).

Pros – At an empty weight of 430 pounds (with the HKS engine), you can add numerous systems and stay within the training exemption definitions. Beautifully instrumented front and rear. Fuel quantity couldn’t be much easier to check; glance out either side. Many system accessories offered by factory.

Cons – Brakes were rather weak on this plane. Flaperons were not installed on this particular Chinook. Great instrument deck requires more familiarity to fully use; a quick checkout isn’t enough. No trim.

Cockpit/Cabin

Instrumentation; Ergonomics of controls; Creature comforts; (items covered may be optional).

Pros – Rear seat had good instrumentation; would make a good trainer vehicle so equipped. Seats were quite comfortable for longer flights. Wide bodied pilots should love the Chinook. Even with doors, the interior is very large. Interior upholstery and floor pans make the inside more polished.

Cons – I didn’t care for the combo throttle much. The front pilot must reach slightly behind your left side while a rear seat instructor would have to lean forward. Rear seat entry is much more difficult than the front seat. Aft occupant is very near engine.

Ground Handling

Taxi visibility; Steering; Turn radius; Shock absorption; Stance/Stability; Braking.

Pros – Solid and comfortable, built “Canadian tough,” the Chinook taxies with authority. Wide gear geometry and wide tires helped the effect further. Good turn radius even while taxiing slow in stronger winds. Bungee suspension worked well to soften the bumps. Adequate ground clearance and a protected prop arc.

Cons – Rear seat visibility is poor; an instructor will have to plan ahead to check traffic before takeoff. No brake lever at rear seat (not uncommon on trainers, though). No differential braking at either seat.

Takeoff/Landing

Qualities; Efficiency; Ease; Comparative values.

Pros – This is one of the easiest-to-handle taildraggers you can fly. A nearly flat deck angle helps as does a low posture. Terrific front-seat visibility during any takeoff or landing operation. Approaches can be made quite slowly (down into the 40s).

Cons – Chinook didn’t jump off the ground as quickly as some trainers. Rear-seat visibility is quite compromised on takeoffs and landings; an instructor will have to stay aware of traffic and judge landing speeds and attitudes well (though, of course, such judgments are expected of instructors).

Control

Quality and quantity for: Coordination; Authority; Pressures; Response; and Coupling.

Pros – Roll response and roll rate were both quite brisk. Roll rate was not as strong as roll-in/out power, but authority proved good even in breezy crosswinds. Tail has loads of power, too, but forces are a little higher. Cable connections to tail surfaces gave good feedback.

Cons – Coordination takes a few minutes to learn because the ailerons feel somewhat lighter (though perhaps a little less potent) than the rudder. Control adjustments may account for these observations.

Performance

Climb; Glide; Sink; Cruise/stall/max speeds; Endurance; Range; Maneuverability.

Pros – The Chinook shows strong sink rate performance, especially for a design that appears to (though may not) have a larger frontal area. Purred along beautifully with its HKS 4-stroke engine. Speeds ran about 80 mph in a medium-high cruise setting. Also flew well at only 45 to 50 mph.

Cons – Carrying the extra weight and complexity of a 4-stroke engine means some performance is diverted to this purpose. Climb rate also didn’t seem up to the factory brochure figures (though I’m comparing the 60-hp HKS to a 50-hp Rotax 503 and a 65-hp 582).

Stability

Stall recovery and characteristics; Dampening; Spiral stability; Adverse yaw qualities.

Pros – Stalls were quite straightforward in the Chinook (I only flew solo). Often one wing would fall, and not the same one, but the fall was slow and modest. Unable to see a full-power stall break. Accelerated stalls always fell to the outside, which is preferred. Solid aircraft in breezier conditions.

Cons – Without trim, and with the nose slightly heavy, I could not make longitudinal stability checks. No standard shoulder belts; lap belts only are usually considered insufficient in case of violent upset.

Overall

Addresses the questions: “Will a buyer get what he/she expects to buy, and did the designer/builder achieve the chosen goal?”

Pros – ASAP offers a good value, I think, at $7,250 for the basic airframe. Easy flying characteristics endear the Chinook to either training, cross-country flights or bush flying. Present company has outlasted the original design company and provides more certainty with which to do business. Company makes most parts in topnotch in-house facility.

Cons – The Chinook has not changed much over the last decade; if you’re looking for something new and dashing, this may not be it. No extensive U.S. dealer network.

Prices please!….

Here is a newer Chinook article where you can inquire further.

This is an old review. I was wondering if you plan on re-reviewing this since they now offer the 912 version and the Dan Reynolds STOL options. With the more recent popularity spike in STOL aircraft like Kitfox, the cost has driven up so much. Options like the Chinook might be nice alternative for working class that can’t afford $100k airplanes.

To do such a review, I have to have access. If an opportunity presents itself, I will.

I have acquired a Chinook Plus 2 and need to trailer it home. You have a good website but no information on landing gear width (to outside of the gear). With the wings removed, what is their lenght. Please and thank you.

If you have the aircraft, I’m not sure why you can’t just go measure those things to know for sure. However, if you want to ask the now-U.S.-based producer of new Chinooks, follow this link.

I just purchased a chiniok single seater would like to be able to talk to a live person with questions that may arise

Here’s your contact info:

John A. Couch

Aeroplane Manufactory

Gloster Aerodrome

4695 Gloster Lane

Sealy, Texas USA 77474

http://www.AMplanes.com

http://www.glosteraerodrome.com

Would you have installation instruction for a Rotax 582 on a Chinook?

Hi Terry: This website does not have those instructions but a Rotax representative may be able to help.