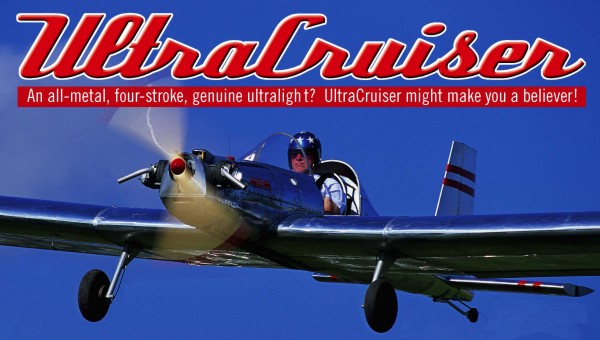

The new light-sport aircraft (LSA) category will soon be a reality. While a best guess is that FAA’s newest rules could be announced at EAA AirVenture Oshkosh later this month, it may happen later in the year. Whenever it happens, and like many others watching closely, I hope this new concept arrives swiftly with its promise of interesting aircraft at affordable prices.

As important as LSA may be, however, the proposed new the rule doesn’t affect other enjoyable flying machines. Aircraft built under the amateur-built (51-percent) rule will continue to be a major factor. Many EAA members are building under this rule, and these aircraft will continue to offer wide choices, performance beyond that of many general aviation aircraft, and the pride of craftsmanship. LSA also leaves room for Part 103 ultralights to continue and grow. While some industry leaders see little demand for single-seat aircraft powered by small engines-and it is true that they do not make up a majority of machines-neither, however, will they disappear. The UltraCruiser is one good example of why this statement is true.

Room for Part 103 Vehicles … and More

One of the main appeals of the new sport pilot certificate-the pilot side of FAA’s proposed new rules-is that a valid U.S. driver’s license will serve as medical certification. That’s good. But pilots who’ve lost their third-class medical aren’t grounded today-if they are willing to fly Part 103 vehicles. Most of those who believe few 103 ultralights are available still admit these aircraft offer charms of flight not possessed by other powered aircraft. Simply put, ultralights are fun to fly. They cost less, assemble quicker, use less fuel, handle crisply, land and stall slowly, and transport easily.

In my research, I’ve found more than a dozen ultralight vehicles that can qualify under FAR Part 103-the rules that govern ultralights-and that’s after eliminating designs that require engines like the Rotax 277, which has ceased production. In fact, consider aircraft like the Kolb Firefly, Phantom X-1, Aero-Lite 103, Hawk Classic, Gull 2000, several Fisher models, T-Bird I, miniMAX 103, N-3 Pup, MX Sprint, RANS S-17 Stinger, SkyStar’s Kitfox Lite, along with several other models of lesser popularity. All these aircraft can make Part 103 weight and speed with the Rotax 447 or 2si 460 engine, which gives these machines sprightly performance.

So, don’t tell me “no legal 103 aircraft exist.” Such a statement simply isn’t true, and all those companies wouldn’t keep offering those machines if none ever sold. However, I can think of only a couple of these machines that can make weight and speed of Part 103 with a four-stroke engine. The UltraCruiser is one of them.

The four-stroke power on the UltraCruiser comes from a 1/2 VW conversion. In my experience flying the UltraCruiser, this four-stroke powerplant brought a quieter yet rumbling sound more agreeable than a two stroke’s whine, while delivering plenty of get-up-and-go. On top of everything else, the 1/2 VW costs roughly the same as the Rotax 447, while using less fuel and having lower long-term maintenance costs.

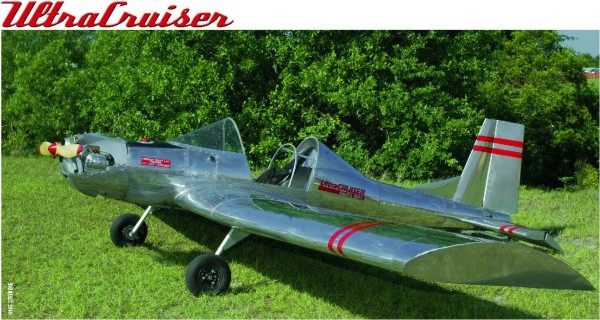

The UltraCruiser is also an all-metal design. You won’t be able to add paint because of Part 103 weight constraints, so the finish is polished and gleams in the sun, and it won’t wear out as fast as Dacron-covered wings.

Put a price tag of $8,000-$10,000 on the UltraCruiser, and you can see why people are looking at this attractive Part 103 ultralight vehicle that can also be built in the experimental amateur-built category. In this article we’ll explore this design more fully, but remember, you do not need to wait for FAA’s new rules to be finalized to start building and flying an UltraCruiser.

If the UltraCruiser isn’t big enough for you, or perhaps you prefer a faster aircraft using the Rotax 503 or 912 engine, or maybe you want electric start or paint or other options that push the UltraCruiser over 103’s stringent weight limit, Hummel Aircraft has a selection.

The Ohio company makes the UltraCruiser Plus-for larger pilots-or the Hummel Bird, which is faster. Neither of these choices with their more powerful engines can make the definitions of 103. Yet they are similar in design and, I have to believe, equally enjoyable to fly.

Building any Hummel project will consume 400-600 hours and that can translate to a number of years for some builders. Some older pilots have shied away from lengthier projects, believing that by the time they complete the plane, their third-class medical might be lost. In this case, LSA won’t come to the rescue; Hummel may or may not decide to qualify their aircraft. But the sport pilot certificate can help.

If you build the aircraft to fit the 51-percent rule, you can still fly the UltraCruiser Plus or the Hummel Bird, as those aircraft easily meet the definition of aircraft that sport pilots will be allowed to fly. The driver’s license medical part of the sport pilot certificate can save the day.

So regardless of the status of LSA rules, owners could start building any Hummel aircraft-UltraCruiser, Ul-traCruiser Plus, or Hummel Bird-and they should be able to operate them with their sport pilot certificate. The ultralight UltraCruiser requires no pilot certificate or FAA registration.

Morry’s Story

Though Terry Hallett now owns Hummel Aviation, Morry Hummel created all the Hummel designs. Here’s a man with a long aviation heritage. In fact, the aircraft subject of this review was not designed by Morry until he was in his mid-80s. How that happened is an inspiring story in itself.

According to Morry, it went like this: “On July 19, 1995, I crashed my miniMAX|and lost my right leg below the knee. My left leg was badly broken, and my face crushed. My teeth were wired shut for 10 weeks and I was fed through a tube in my stomach. While I was in the hospital for five months, I had time to think. God had spared my life for a reason. My first UltraCruiser is named ‘God’s Gift’ because I am only 85 years young and flying again.”

Personally, if I manage to reach the vintage age of 85 years, I’ll feel fortunate if I can keep flying safely. I cannot imagine going through such a devastating accident, spending all that time in the hospital, and then starting to design a new aircraft. Morry Hummel is clearly an aviator with amazing drive and tenacity.

In July 2002, Terry Hallett bought Hummel Aviation from Morry and his wife. Terry says he only got involved to help upgrade the drawings, but he ended up purchasing the enterprise. He’s quick to add, “Morry still comes in every day.”

Indeed, Morry’s still at it. Those of you in the region around Ohio can travel to Fulton County Airport in Wauseon, Ohio, and meet the man himself, as over the July 12-13, 2003, weekend Morry and Scott Casler will host the VW engine fly-in.

For a year and a half, Scott has produced Morry’s converted VW engine in a location away from Hummel Aviation. He bought the engine side of the operation and established Hummel Engines.

Four Strokes, Two Cylinders

The UltraCruiser is powered by a 1/2 VW engine that produces 28 to 37 hp. The higher-power version was mounted on the test aircraft I flew, yet it burns only two gallons per hour, making it one of the most fuel-efficient engines you can install on an ultralight.

Though a 1/2 VW lacks the same power-to-weight ratio of two strokes, four-stroke engines hold a large appeal among many pilots. Their noise is more neighbor friendly than most two strokes, their fuel economy is substantially better, thus ecological concerns favor the four stroke over the two-cycle engine.

With increasing interest in four-stroke engines in the light aircraft community, Hummel’s 1/2 VW conversions may offer what many pilots want-four-stroke power at a cost that fits most budgets. While the respected Rotax 912S runs $12,000, you can get into a completed Hummel 1/2 VW for somewhere over $3,000. Naturally, this isn’t a fair comparison; the Rotax is much more powerful and it comes complete. But at these low prices, many pilots’ needs can be addressed.

Scott Casler of Hummel Engines says the 1/2 VW-in 28-, 32-, or 37-hp models-weigh 85 pounds with exhaust and a Slick magneto. Respectively, their cost is $2,500, $2,700, or $3,250 without a prop or prop hub. With everything needed to fly, engines used in Hummel’s factory planes weigh 92 pounds, says Terry Hallett. While heavier than a two stroke, this is a tolerable weight. After all, the UltraCruiser makes Part 103 with a four stroke engine!

Pilots choose 1/2 VW engines, Terry Hallett says, because they’re “so darn reliable and simple.” In addition, VW clubs, shops, and enthusiasts across the country assure the availability of replacement parts far into the future. Terry says parts for the VW engine are, “virtually an infinite supply. Many parts are being made new today.”

If you’re still worried that a Volkswagen Beetle engine can’t be enough for your airplane needs, remember that performance increases are possible because auto racers and others are developing speed kits for the trusty powerplant.

But for those whose power aspirations are even greater, Hummel Engines has been working on a full VW engine. “Scott builds this engine for the Sonex and Kitfox aircraft, among others,” explained Terry. He says prices are in the range of $4,500 with starter and electrical system. The more I hear about these VW engines, the more amazed I am that they aren’t used more often on ultralights.

Perhaps one of the downsides is that the engines are sold as kits, as indicated on Hummel Aviation’s website. Terry clarified that, saying, “Plans are sold to convert the 1/2 VW. Then you can buy parts from Hummel Engines or other suppliers to make the engine flyable.” Yet Terry says most Hummel 1/2 VWs are sold as ready to mount.

Getting Fired Up

To hold the UltraCruiser to Part 103’s strict weight limit with a four-stroke engine, you can’t have pull or electric starting. That leaves hand propping. Some pilots actually enjoy the experience, but I was happy to have someone else spin the stick when I was ready to go flying. Thanks, Jon Jacobs!

Most pilots will like the view over the UltraCruiser’s nose during taxiing. You hardly need to S-turn to see forward, unlike many taildraggers.

As I taxied to the runway, I kept recalling other 1/2 VW experiences. While the humble 1/2 VW lacks the big engine sound of the more potent HKS, Jabiru, or Rotax engines, it’s audibly different than any two stroke. VW engines also please pilots accustomed to flying with Lycoming or Continental engines because they give a similar tach reading.

After a few minutes behind the Hummel 1/2 VW, I came to intensely like this little engine. A couple times in flight I removed all ear protection and was surprised at the low noise level.

Compared to the Rotax 582’s 64 hp or even the 503 and its 50 horses, the 1/2 VW with 37 hp sounds rather weak. The Rotax 277 with its single cylinder is close at 28 hp, and the lightweight 2si engine yields nearly the same power with many less pounds. Nonetheless, UltraCruiser was quite sprightly in its performance.

Upon opening the throttle on the 1/2 VW, the results are much different than a two stroke. Two-cycle engines spool up much faster and give an initial sensation of greater power. But the VW’s power grows quickly once the revolutions rise; you’ll be pleasantly surprised at the acceleration. Launch roll was brief at perhaps 100-150 feet.

No Heavy Metal

While waiting to fly, I’d examined UltraCruiser’s all-metal airframe, rare among Part 103 ultralights. Most designers will admit that aluminum is an excellent way to keep weight low. Metal also lasts a long time, and we know a lot about aluminum, so inspecting it is fairly straightforward. Contrarily, an all-metal design brings extra build time and complexity.

At my average size (70 inches and 175 pounds), I found the UltraCruiser roomier than expected from the outside view. Once inside, you’re still surrounded by shiny metal. It made a preflight exam of the interior that much easier.

On the ground, taxi steering effectiveness was quick and easy with the tailwheel UltraCruiser. Differential heel brakes were more than adequate and allowed tight maneuvering. My heels slid readily on the interior’s metal finish, making the levers easy to operate. The UltraCruiser felt very stable on the ground thanks to a wide gear track; a 6-1/2-foot stance made for improved ground handling.

However, taxi steering in the UltraCruiser is a bit different. Instead of rudder pedals, you push on a foot bar- a solid bar that pivots much like the go-cart you made as a kid. But, pedal extensions-not unlike what children have on their first tricycles so they can reach the pedals-made the pivoting bar feel much like actual rudder pedals. Overall, control experience was satisfying.

After powering up on the takeoff toll, the UltraCruiser’s tailwheel lifts quickly and its ground run was short. The lightweight of this machine makes it a delight to launch. The UltraCruiser showed no tendency to overlift the tail when you ease the joystick forward.

Landing also went well. On my first trials, I approached at 70 mph to allow plenty of room for error, and slowed to 60 mph over the threshold. Later I discovered that I could make an approach at considerably slower speeds, in the area of 45 mph, which significantly decreased the ground roll. The UltraCruiser’s stall speed is below 30 mph, according to the installed airspeed indicator (though they are notoriously incorrect at such speeds and angles of attack). Once down in ground effect, the Ultra Cruiser rounds out very cooperatively and sustains height above the runway very well.

In my later landing efforts, I came to respect UltraCruiser’s slip capability. Because the design does not use flaps-part of the weight reduction program-slipping is necessary for short runways. Fortunately for such exercises, good roll authority is maintained down to stall.

Ultra Cruisin’

What a hoot to fly this plane! While not in the range of aerobatic aircraft, roll response was quite brisk, faster than your average ultralight by a clear margin. Having heard that Morry’s older Hummel Bird design was noted for its ability to roll 360 degrees in three seconds, I’d been waiting to feel the UltraCruiser out. Perhaps because it flies slower than the Hummel Bird, the UltraCruiser is not as quick in roll, but it was certainly responsive.

A short wing span of 25 feet and a small wing area of 94 square feet help provide the control crispness, but to put it in perspective, the Hummel Bird uses even smaller wings (18-foot span and 57 square feet of area). Flying with so little wing area shows the benefit of light weight.

Morry learned control systems a long time ago, and his well-evolved controls were beautifully harmonized and delightful to use. I adjusted to them quickly finding the UltraCruiser very desirable to fly. I believe most pilots with a few hundred hours logged will feel the same, though novices will want to take it easy at first.

In aggravated handling, I found the rudder was slightly weaker than the ailerons. I only found this by slipping very hard to a landing where I was able to exhaust the rudder range at relatively slow speeds. This is the most critical I can be regarding UltraCruiser’s handling characteristics.

My test UltraCruiser had 37 hp and would hit 75 mph with about 3100 rpm. By comparison, in a maximum climb-out I noted 3350-3400 rpm with the throttle wide open. The tachometer topped out at 3500 rpm, the highest numeral on the air speed indicator (ASI).

Cruising around at 2,000 MSL, the engine produced 63 mph at 2700 rpm. A tiny bit more power, 2750 rpm, brought the UltraCruiser to 70 mph according to the installed ASI.

All my flight evaluations showed stalls to be quite mild. They always broke through, dropping the nose, but not radically. I didn’t find any tendency for the UltraCruiser to drop a wing at stall.

The UltraCruiser also behaves well in response to power changes. When you add power the nose rises, though not swiftly. Reducing power tips the nose downward slightly. The thrust line seems well chosen.

Ready to Start Bending Metal?

Plans for the UltraCruiser are $280, including a Morry Hummel video providing details of construction and flying. A number of prefabricated parts are available-Hummel Aviation’s Internet site offers photos of the parts you can buy-but you’ll have to source your own metal and perform a significant amount of basic fabrication. Their information will help you choose places to buy parts.

Hummel Aviation’s building plans are something like those from Fisher Flying Products. Many parts are drawn in full size, letting you build directly on the plans to ensure greater accuracy. Builders tell me this saves a lot of time compared to scaling up from smaller drawings or creating drawings from measurements.

Nonetheless, forming the metal parts to build the fuselage and wings will consume about half of the 600 hours it will take to build the UltraCruiser, says Terry Hallett. “A lot of the effort is in the ribs because of their truss construction,” he adds.

Buy all the parts Hummel Aviation sells, and you can chop 200 hours off the 600 total. If you also choose their new quick-build wing, you can reduce the total to 320-340 hours, the company says. Choose optional parts from Hummel Aviation, and you’ll increase your investment in dollars while decreasing your investment in labor hours. Yet even with instruments and a couple optional extras of modest weight, you should stay well below $10,000 for a long-lasting, joyful Part 103 ultralight vehicle.

If building sounds like fun and you really love a good flying aircraft, UltraCruiser, UltraCruiser Plus, or a Hummel Bird might be your kind of flying machine.

| Seating | 1 |

| Empty weight | 254 pounds 1 |

| Gross weight | 500 pounds |

| Wingspan | 25 feet |

| Wing area | 94 square feet |

| Wing loading | 5.3 pounds per square foot |

| Length | 16 feet |

| Height | 48 inches |

| Fuel Capacity | 5 gallons |

| Kit type | Construction 2 |

| Build time | 600 Hours 2 |

| Notes: | 1249 pounds without shock-absorbing gear. 2Build time is 400 hours with prefabricated ribs; and a ready-to-assemble wing is coming soon, saving another 60 to 80 hours for a total of 320 to 340 hours. |

| Standard engine | Hummel Half VW, 37 hp at 3,500 rpm |

| Power | 25-40 hp |

| Power loading | 13.5 pounds per hp |

| Cruise speed | 60-80 mph |

| Stall Speed | 28 mph |

| Never exceed speed | 95 mph |

| Rate of climb at gross | 1,000 fpm 1 |

| Takeoff distance at gross | 150 feet |

| Landing distance at gross | 150 feet |

| Range (powered) | 160 miles (2.5 hours) |

| Notes: | 1 As tested with 37 hp 1/2 VW; test aircraft may not have met Part 103 as equipped. |

| Standard Features | Hummel Half VW 4-stroke engine, cantilever wing, monocoque construction, mostly enclosed cabin, detachable wings, steerable tailwheel, all-metal coverings. |

| Options | Engine power choices from 28 to 37 hp, shock-absorbing gear, remote choke, mechanical or hydraulic brakes, alternative props, instruments, quick-build wing option coming, tinted canopy and windshield, cabin heat. (Note: Some items are supplied by companies other than Hummel Aviation and the addition of some items will disqualify the UltraCruiser from Part 103 participation.) |

| Construction | All-aluminum airframe, formed aluminum wing ribs, small steel parts. Made in the USA and distributed worldwide by an American company. |

Design

Cosmetic appearance, structural integrity, achievement of design goals, effectiveness of aerodynamics, ergonomics.

Pros – All-American design for those who enjoy single-place flying. Cantilevered wing with no struts. Designed around 4-stroke power, which many pilots prefer. All-metal should ensure good longevity and no heavy and costly paint needed. With optional canopy, the UltraCruiser has a P-51 look.

Cons – Challenge of building this kit will eliminate it from interest by many pilots and already-built ones for sale are scarce. Some ultralight buyers believe riveted structures are more vulnerable than aluminum tube frames and certainly damage repair would be more time-consuming.

Systems

Subsystems available to pilot such as: Flaps; Fuel sources; Electric start; In-air restart; Brakes; Engine controls; Navigations; Radio; (items covered may be optional).

Pros – Four-stroke power is worth giving up systems to some pilots. Vernier throttle on test aircraft was an interesting feature. Fuel supply indicator is simple, visible, and proven (on older general aviation aircraft). Differential brakes were easy to operate. Test aircraft had a cockpit choke control.

Cons – No flaps or in-flight trim can be accommodated if UltraCruiser is to remain within Part 103. Lack of pull starter or electric starter (to stay within Part 103’s weight limits) is a no-deal to some buyers. Engine access comes only after removing cowl.

Cockpit/Cabin

Instrumentation; Ergonomics of controls; Creature comforts; (items covered may be optional).

Pros – Panel has enough for the basic instruments you’ll need and it’s within easy reach for adjustments. Cabin is roomy enough for pilots weighing less than 200 pounds and less than six feet tall. Four-point seat restraints were appreciated. Optional full bubble canopy available, even tinted, though the open cabin is a delight in good weather.

Cons – Entry won’t be easy for some less agile owners. Some builders will yearn for more panel space for goodies. Long flights will require extra attention to seat comfort. Very limited cargo area. No seat adjustment provided unless builder adds it.

Ground Handling

Taxi visibility; Steering; Turn radius; Shock absorption; Stance/Stability; Braking.

Pros – Very precise and responsive tailwheel response. Superb visibility while checking for incoming traffic. Differential braking on test aircraft aided ramp maneuverability. Wide gear track gives great ground stability.

Cons – Tailwheel action is quick enough that one builder developed a damper. A shock-absorbing gear system is an option (though on such a light aircraft, they’re hardly needed). Elevator sits very close to ground if field is rough; inspect carefully.

Takeoff/Landing

Qualities; Efficiency; Ease; Comparative values.

Pros – Half VW engine provides surprising pep on takeoff runs, which are about 150 feet. Landing touchdown is very easy due to potent ground effect. Excellent visibility throughout landing approach. Good crosswind capability. Moderate slips work well. Approaches can be done down to the 40-mph range.

Cons – No flaps to aid steep approaches to short fields or in emergencies (however, slips are reasonably effective). Ground clearance is minimal at tail; keep your tail flying in the event of an out-landing. Long ground float will stymie landings after a too-fast approach.

Control

Quality and quantity for: Coordination; Authority; Pressures; Response; and Coupling.

Pros – Light, brisk response from ailerons. Roll rate is better than the average ultralight, perhaps due to small wing and short span. Precision turns to headings were straightforward. Substantial crosswind capability. Steep turns went well as did Dutch roll coordination exercise.

Cons – Rudder response is weaker than ailerons (suggesting harmony shouldn’t be as good as it feels). Ailerons may be a bit fast for some less experienced pilots. No other negatives.

Performance

Climb; Glide; Sink; Cruise/stall/max speeds; Endurance; Range; Maneuverability.

Pros – Little plane that carries its own weight in useful load. Climb is very vigorous at 1,000 fpm. Takeoff roll start is surprisingly energetic for a small 4-stroke engine. As tested – with a prop that won’t work under Part 103 – speeds hit more than 75 mph. Burns only 2 gph; good range even with a 5-gallon fuel tank.

Cons – Four-strokes don’t spool up as rapidly as 2-strokes, something to keep in mind if you need a quick burst of power, say on approach to landing. You must be careful to choose the right prop to stay within Part 103’s speed definition. No flaps to permit low and slow over-the-field flying.

Stability

Stall recovery and characteristics; Dampening; Spiral stability; Adverse yaw qualities.

Pros – Many pilots believe safety is enhanced when the engine is in front of the pilot. Secure seat belts were installed on test UltraCruiser. Good power response test; power-up raised the nose and vice versa. Stalls broke only modestly and with good warning.

Cons – Longitudinal stability test didn’t work well as the UltraCruiser has only a fixed trim tab that wasn’t perfect for my weight (though light elevator forces made coping easy). Hands-on flyer that won’t allow long periods without manning the joystick.

Overall

Addresses the questions: “Will a buyer get what he/she expects to buy, and did the designer/builder achieve the chosen goal?”

Pros – The UltraCruiser makes Part 103 and so can your 4-stroke-powered ultralight. Based on proven Hummel Bird design, which has a long history. Wings can detach for transport (though not a fast-folding wing). Bargain price by anyone’s standard: can be flying for less than $8,000.

Cons – Build times are lengthy, even the fastest configuration is more than 300 hours. More affordable kits call for lots of “tin bending.” Full kit with every part supplied is not available. No 2-seat models are available or planned. Thin aluminum construction could see hangar rash more easily.

Looking at the statistics, I have a 1,000′ strip ditch to ditch with power lines under ground on highway end an marsh on the other end, what can one expect on landing approach as far as air speed travel in ground effect and role out. In your opinion am I pushing the envelope of landing on my 1,000 runway. Thank You so much Walt O’Neal Belhaven NC 252-943-8265

It is always best to direct questions like yours to the seller of this aircraft but I think it could handle that length runway quite well. I cannot comment other obstacles without seeing the airstrip.