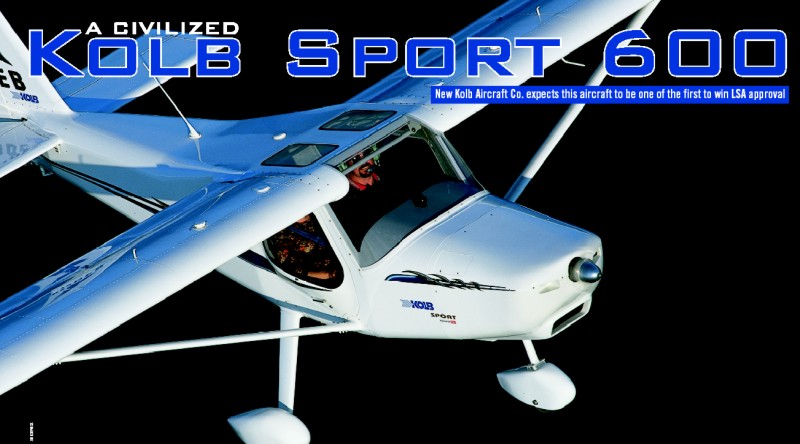

The Kolb Sport 600 features a composite fuselage and all-metal wings and control surfaces. The main gear legs are heat-treated 4130 chromoly steel tubing while the front nose gear uses a 4130 chromoly gear leg and aluminum fork. Originally introduced in Canada as the Pelican Sport, the New Kolb Aircraft Company is currently selling 51-percent kits and expects the aircraft to meet ready-to-fly Special light-sport aircraft status when FAA finalizes the light-sport aircraft rule.

The aircraft flown by Dan Johnson for this report was the taildragger version of the Sport 600, which is the personal aircraft of Bruce Chesnut, president of the New Kolb Aircraft Co. The design is available as either a taildragger or tricycle gear and can be adapted to floats or skis. Currently 50 Sports are flying in the United States today while another 300 are in operation in Canada and other countries, making the aircraft a well-proven design. (Helen Melburn photo courtesy of New Kolb Aircraft Co.)

Flip-up doors ease entry and exit into the aircraft and offer great visibility to the side, as do dual Lexan skylights in the ceiling of the cockpit. Flip-up doors also ease operations on floats.

The instrument panel of the Sport 600 allows generous room for a variety of instruments to meet most pilots’ requirements. This VFRequipped Sport 600 features an electronic instrumentation system (EIS) as well as standard airspeed and attitude indicators and engine monitoring gauges. Exactly what instruments a special LSA version of the Sport 600 will feature has not been finalized.

Bruce Chesnut is the president of the New Kolb Aircraft company, leading the venerable company founded by Homer Kolb into the future.

My first thought when I exited the Kolb Sport 600 after flying it was, “This is a very civilized aircraft.” Is that typical of what we can expect when light-sport aircraft (LSA) become the law of the land? I sure hope so|though I also hope Part 103 ultralights and kit aircraft continue to enjoy a solid share of the overall market.

With its sleek composite exterior, all-metal wing, custom interior, international (Canadian) design heritage, and cross-country performance, the Sport 600 from New Kolb Aircraft sets a pace others may hope to follow.

My test airplane for this month’s article was the personal property of New Kolb Aircraft owner Bruce Chesnut. That explains the gorgeous interior finished by a professional in Alabama: Leather-covered seats and fittings, tasteful embroidery, and beautifully formed and finished plastic covers graced the aircraft. Bruce’s Sport 600 also had attitude (IFR, or instrument flight rules) instruments, which is rare in the ultralights or kit-built aircraft I typically review.

I had the occasion to fly the Pelican from Ultravia, from which the Kolb Sport 600 evolved, several years ago, and this new model is a clear improvement of the species. The Pelican flew well then, and the Sport 600 does so now, too, but the designers and the New Kolb Aircraft Co. have done a lot of refinement, and the Sport 600 is now poised to become one of the earliest LSA entries.

Before we have a closer look at this potential LSA, however, we must remind readers that the final parameters that will define what is or is not a lightsport aircraft won’t be known until the final sport pilot and light-sport aircraft rules are released. At that time, manufacturers may have to make adjustments for their aircraft to comply with the definition. In addition, each manufacturer will have to show compliance with the consensus standards for that category of aircraft-that is, fixed wing, powered parachute, or trikes. Only after meeting both requirements will an aircraft officially qualify as an LSA.

The Boss’s Plane

Bruce elected not to accompany me while I stalled and steep turned the airplane for an hour plus. But he gave me a good verbal checkout, and then we reviewed the aircraft’s switches and knobs. There are quite a few of each in his personal Sport 600 because of the IFR instrumentation.

Getting in the luxurious cockpit requires a lean-back movement. Grab hold of the strut and door frame and lower yourself back into the pilot’s seat. While still thusly braced, raise your right leg up and over the joystick. At this point you can slide back into the seat and bring in your left leg. The front edge of the seat is forward of the doorframe, and the seat bottom is long (and comfortable). If you don’t use this procedure and simply sit down as I did, you’ll probably have to use your arm to bring in your right leg.

Bruce told me I’d have a lot of rudder authority, and he was right. During taxi operations all maneuvers were quite precise; however, you must fishtail back and forth during taxiing because you cannot see over the nose. In fact, Bruce had offered a seat cushion to raise me, and I should have accepted. The seats were rather low, which is well suited for a tall person but too low for someone of my average height. Of course, a kit builder can make changes as needed.

The Sport 600’s seats were quite comfortable, despite their aft rake on the ground. In flight they felt right, and visibility over the nose was unobstructed. The overhead skylight was tinted green, a pleasant change from the usual clear, and it cut the heat from Florida’s bright sun.

Bruce did not fit his Sport 600 with an in-flight adjustable or constant-speed prop because these items won’t be permitted under the proposed LSA rules. But he did equip the plane with a radio and a transponder so he could fly it cross-country to air shows.

When I started the engine and it caught rapidly, the blast of air took the door out of my hand and slapped it noisily against the underside of the wing. Bruce said he’ll remedy that problem with a gas piston. This aircraft had dual fuel drains under the wings that hung down into the airstream such that the doors could strike them. Bruce said he’ll also recess the drains on later models.

You could fly this aircraft with the doors off, but I’m told you wouldn’t want to open them in flight, probably as the lift caused by their curved shape could overstress the hinges. However, on warm summer days, I’ll bet the plane would be fun with no doors. Even with the doors on, side visibility was good, as the window is set into the top two-thirds of the door.

A long lever between the seats operates the aircraft’s flaps. A detent button allows you to fix the position, but when deploying the flaps, the pulling air loads were significant. When you deploy the flaps, the ailerons also droop a bit in a ratio of about 3-to-1 to assist the flap operations. The ailerons then have some reduction in their total effect since they’re drooping on both sides.

The brakes were quite strong, as advertised. And the Sport 600’s full swiveling tail wheel helps you push the bird back into a hangar or tie-down spot. Although the airplane weighs 720 pounds empty, it’s easy enough to handle on the ground.

I found it slightly awkward to fly with my left hand on the stick. I’d prefer my right hand on the stick and left on the throttle, but the Sport 600 locates its one throttle in the center. Cessna or Piper drivers may not notice this because they use their left hand on the yoke and right hand on the throttle. In the future I might fly the aircraft from the right seat (where I’ve done a lot of duty as a flight instructor). I could better finesse my landings with my right hand on the stick.

Quick Takeoff

Feeding the throttle of the Rotax 912S engine to 100 hp gives an inspiring sensation of power in this aircraft. Loaded to about 1,000 pounds (I was solo and 300 pounds under gross), the Sport 600 zoomed off the runway behind its 912S and immediately took on a well-behaved attitude. Years of working on this basic design have resulted in a finely achieved airplane.

Bruce Chesnut chose to build a taildragger -you can build the aircraft either as a taildragger or tri-gear-and the Sport 600 is said to perform and behave well on floats. I loved that my evaluation aircraft was a taildragger, yet taildraggers aren’t for everyone. Bruce said he’s still struggling to have consistent, perfect landings. He admitted, “If I only have a one-lurch landing, that’s pretty good.” He means a less than squeaky-smooth touchdown of wheels to ground with no rebound.

Bruce identified the problem that half of all pilots have with taildraggers-getting the speed down for a three-point landing means holding the nose high, which interferes with your ability to see forward, requiring a new technique right in the middle of your landing touchdown. I look to the side and feel my way down; others use peripheral vision, taking in both sides. Many just say no to taildraggers.

The other problem for pilots who struggle to land taildraggers is that they don’t have happy feet. If you don’t keep the rudder and tail wheel moving in short, regular applications, you could enter a ground loop. For these reasons, New Kolb Aircraft expects most sales will be the tricycle-gear Sport 600.

Bruce had encouraged me to do wheel landings and suggested that if I rebounded I should ease the stick forward. I replied that I wasn’t really comfortable doing that because a known rut in South Lakeland’s runway might help the airplane nose over, especially if I acted too forcefully with forward stick motion at a higher speed. Instead, I sought to do the usual slow, three-point touchdown that is the holy grail of taildragger pilots.

I bounced a little (or lurched as Bruce said) on the first effort, but I knew it didn’t challenge the structure. Subsequent trials got better, mainly, I think, because I kept the speed down. On that first landing, I let my speed creep up and then had more energy to dissipate. Slower approaches with generous flaps seemed to work well. Fortunately, the Sport 600 handles well at slow speeds.

I made four landings that I thought were pretty fair. The New Kolb Aircraft folks, Bruce Chesnut and Norm Labhart, didn’t exactly glow over my touchdowns, but they seemed to think they were satisfactory. With a bit of practice and patience, the technique should become well ingrained.

The Sport 600’s wheelpants were cowled tightly enough that as we pushed the aircraft back into a new T-hangar with a fresh concrete apron, one wheelpant scraped slightly as we hit a lip. Tight-fitting wheelpants give me some concern on turf runways where a clod of dirt or clump of grass might lodge itself between the wheelpant and wheel, giving the same effect as firmly hitting one brake. My concern notwithstanding, I landed and taxied on sandy soil and experienced no problems.

The Sport 600’s handling is nicely coordinated. I had some initial concerns about stick range. When I tested its range on the ground before flight, I clunked up against the stops rather quickly. This assures you aren’t bumping into your legs. Yet in flight, I found no problem whatsoever with range. You have plenty of capacity and authority in every direction.

I was able to do mild Dutch roll coordination exercises, to about 30 degrees, almost immediately, which speaks well of control harmony. Later in the flight, after gaining more familiarity, I did rolls that were 45 to 50 degrees. In these steeper Dutch rolls, I was still a little sloppy in pitch control, but I had no trouble rolling the nose about the longitudinal axis without initiating a turn.

Steep turns went very well with about 5000 rpm; I never needed to add more power, which is common in other designs. The Sport 600 let me perform 70- degree steep turns and was well behaved in them. The airplane actually wanted to gain altitude at this power setting (at well under gross).

Cross-Country Cruiser

Transportation is a new aspect that LSA will offer recreational pilots. With a 132 mph maximum straight and level cruise speed limit, you can fly faster than most Cessna 172s as well as a bunch of other so-called commuter aircraft. This quality sets LSA apart from Part 103 ultralights, which are not about transport. While ultralights are truly for fun flying, you might rationalize that LSA may have some transportation use.

I found cruising in the Kolb Sport 600 was most comfortable at about 110 mph (corrected), with a power setting below 5000 rpm. Fuel economy is quite good, and you’ll still be moving in triple digits. Noise and vibration seemed especially subdued at 4700-4800 rpm. At this fuelefficient level, fuel consumption may be 2.5 gph, giving a range of more than nine hours. Before slowing down at the far end of downwind, I also used this setting/speed in the landing pattern, so it’s easy to set power and leave it alone for a long flight.

At flat-out power, I recorded a speed of 120 mph indicated. As I constantly repeat, on-board ASIs (airspeed indicators) are often wrong. Bruce told me that based on flights with other aircraft, he believes the instrument is off by about 12 mph at that speed, which, conveniently, means the Sport 600 can hit 132 mph, the exact speed limit specified under FAA’s proposed LSA rule.

During another test run, I observed 112 mph at 5200 rpm. Assuming the same error percentage, this translates to about 124 mph of cruise. This is the setting at which Bruce often flies, earning a respectable cruise that could help the Sport 600 cover a range of 800 miles in six-and-a-half hours.

Typically, I operated below Bruce’s favorite setting of 5200 rpm because I was in no hurry, and I liked the smoother, quieter operation. Bruce said the Rotax 912S will run all day at 5500 rpm, but he indicated he can feel the stress on the engine at that power setting. At full throttle I saw about 5600 rpm, at which point the electronic instrument system (EIS) began to flash at me suggesting I had reached an overspeed condition. Different props can change all this power-setting talk, but for LSA it is likely all planes will come with the same optimized prop.

On short approach and in ground effect at a familiar airfield, I could sense the design produces a good glide angle. Of course, the wingspan is wide for the wing area, yielding an aspect ratio of about 9, and the wing uses no interplane struts, so drag is minimized.

Speaking of efficiency, Bruce lent me his Bose Aviation X headset with a noisecanceling feature that was simply outstanding. The headsets were so quiet I almost wondered if the engine was still running. Of course, at $995, they’d better be pretty good.

The Sport 600 was a little fast for low-over-the-field flying, which I love to do in conventional ultralights. However, the day I was flying Bruce’s airplane the air was quite bumpy from thermal formation, so I may not have experienced its true potential. Even with a couple notches of flaps, I was still traveling about 60 mph, and that simply didn’t feel comfortable down very low.

Good Manners

Stalls in the Sport 600 had very benign characteristics. I wasn’t able to do poweroff stalls at idle thrust, as this engine was idling a bit high. But in low-power stalls, separation appeared to come at 40-41 mph. Bruce indicated the ASI should be corrected at this speed by 2-3 mph, which yields a stall of 42-44 mph, a near-perfect LSA fit.

In some stalls, I thought I noticed some tendency to fall on a wing. The airplane never really did so, but to test my theory, I did a few stalls with a more aggressive entry. Though the nose got very high, the Sport 600 broke only modestly and always straight ahead.

When I did a near-full-power stall, the nose raised so high that it started wandering, and I chose to back off rather than push for a break. I don’t believe I would have reached actual stall, but I wasn’t up for getting unnecessarily aggressive. No ballistic recovery parachute had been installed in this aircraft, and as vice-president of corporate communications for BRS (Ballistic Recovery Systems), I highly favor their use.

I attempted accelerated stalls, and again got the nose rather high, but no clear break was observed. When I got close to this edge, the Sport 600 cooperatively wanted to right itself.

I was able to slow fly the Sport 600 into the higher 4000-rpm range with a couple notches of flaps and consistently hold speed just above stall. I did not have to add power to achieve slow flight, which again suggests an efficient design.

How About You, Sport?

The Sport 600’s composite body and most of its aluminum material come to Kolb from Canadian-based Ultravia Aero Int’l Inc. Kolb then integrates the pieces into a full kit. Bruce Chesnut confirmed the company’s plans to offer a ready-tofly Special LSA.

New Kolb Aircraft believes the Sport 600 will be approved under European JAR-VLA (Joint Airworthiness Requirements- Very Light Aircraft) rules before LSA is introduced. Thereby, they expect to be one of the first Special LSAs on the market along with RANS, Zenair, and Quicksilver. Bruce made a hand gesture about 2-feet high and said the company would have a document stack “this big” in readiness to meet the ASTM standard being created. Today, you can buy a kit Sport 600 for $34,000 with a Rotax 912, 80-hp engine. To get the 912S and 100 hp, you’ll need another $1,500. Those who want all the kick they can get can choose the Rotax 914 engine, but that’ll increase the aircraft’s cruise speed to 142 mph above the LSA limits. And, it will cost them $38,500 to complete the aircraft.

Naturally, the attitude instruments and professionally customized interior are not included in the base kit prices. But New Kolb’s kit comes with lots of factory work already accomplished. For the whole list, go to its website; I think you’ll be impressed. Builders should expect around 900 to 1,000 hours to complete a kit.

It’s likely a fully built, ready-to-fly Kolb Sport 600 will cost in the neighborhood of $59,995, considering American labor and Canadian license fees. An experienced businessman in the food industry, Bruce sees a $60,000 price ceiling for ready-to-fly light-sport aircraft. Whether he’s right or wrong, time will tell. You’ll raise the tab a few thousand more if you equip your Sport 600 like Bruce’s and include costlier items like floats or an emergency parachute.

About 50 Sport 600s are flying today, most originating with the Canadian designer. Ultravia Aero Int’l Inc., our northern neighbor, has built more than 300 planes, all variations based on the Pelican, so this is a well-established aircraft design. Add to that the respected name of Kolb Aircraft in the United States, and you have a formula that should make Sport 600s proliferate under the proposed LSA rules. Kolb believes the orders will flow when the rule is announced, and I’m inclined to agree.

| Seating | 2, side-by-side |

| Empty weight | 720 pounds |

| Gross weight | 1,320 pounds 1 |

| Wing area | 117.3 square feet |

| Wing loading | 11.2 pounds/square foot |

| Useful Load | 600 pounds |

| Length | 19.9 feet |

| Payload (with full fuel) | 462 pounds |

| Cabin Interior | 46 inches at elbow |

| Height | 8.5 feet |

| Fuel Capacity | 23 gallons |

| Baggage area | Full cabin width aft of seats |

| Notes: | 1 The notice of proposed rulemaking for the sport pilot and light-sport arircraft rules listed the maximum gross takeoff weight for LSAs at 1,232 pounds. EAA and others suggested that weight should be raised to 1,320 pounds, which is the current gross weight listed for the Sport 600. The final weight to be allowed won’t be known until FAA releases the final rule. At that time, New Kolb Aircraft Co. may revise the gross takeoff weight, if necessary. |

| Standard engine | Rotax 912S, (80-115 hp) |

| Power | 100 hp |

| Power loading | 13.2 pounds/hp |

| Max Speed | 132 mph |

| Cruise speed | 100-125 mph |

| Stall Speed (Flaps) | 44 mph |

| Never exceed speed | 155 mph |

| Rate of climb at gross | 1,350 fpm |

| Takeoff distance at gross | 300 feet |

| Landing distance at gross | 400 feet |

| Range (powered) | 750+ miles |

| Fuel Consumption | 3.5 gph |

What is the composite body life expectantly for the fuselage? Expiration date? How is the composite fuselage constructed? What signs are some of the high time aircraft showing for wear in this regard. Sheet metal lasts for a long time. Composite is good until it fails, becomes brittle etc.

Need to put long cylinder tubes for gas fuel injection engine. DMANO DAVID