I’d seen the full-size Stampe SV4-RS replica at AERO a few weeks previously, and it really put a hook in me. I was fortunate enough to fly a Stampe several years ago and was very impressed—it being greatly superior to the DH Tiger Moth, with which it is often confused. Of course, even the youngest Stampe is still 69 years old, and they require a lot of maintenance. Spares for the original Renault engine in particular are getting rare, the strength of the wooden fuselage can be compromised from decades of oil being splattered across it and the metal fixtures and fittings are far from the first flush of youth. These are old aircraft and they require a lot of looking after. Indeed, the reason why such aircraft (and cars and motorbikes of a similar vintage) are often referred to as “collector’s machines” is that you often need someone following along behind collecting up all the pieces that have fallen off! (A slight exaggeration but you get my drift).

I’d seen the full-size Stampe SV4-RS replica at AERO a few weeks previously, and it really put a hook in me. I was fortunate enough to fly a Stampe several years ago and was very impressed—it being greatly superior to the DH Tiger Moth, with which it is often confused. Of course, even the youngest Stampe is still 69 years old, and they require a lot of maintenance. Spares for the original Renault engine in particular are getting rare, the strength of the wooden fuselage can be compromised from decades of oil being splattered across it and the metal fixtures and fittings are far from the first flush of youth. These are old aircraft and they require a lot of looking after. Indeed, the reason why such aircraft (and cars and motorbikes of a similar vintage) are often referred to as “collector’s machines” is that you often need someone following along behind collecting up all the pieces that have fallen off! (A slight exaggeration but you get my drift).

Replica Done Right

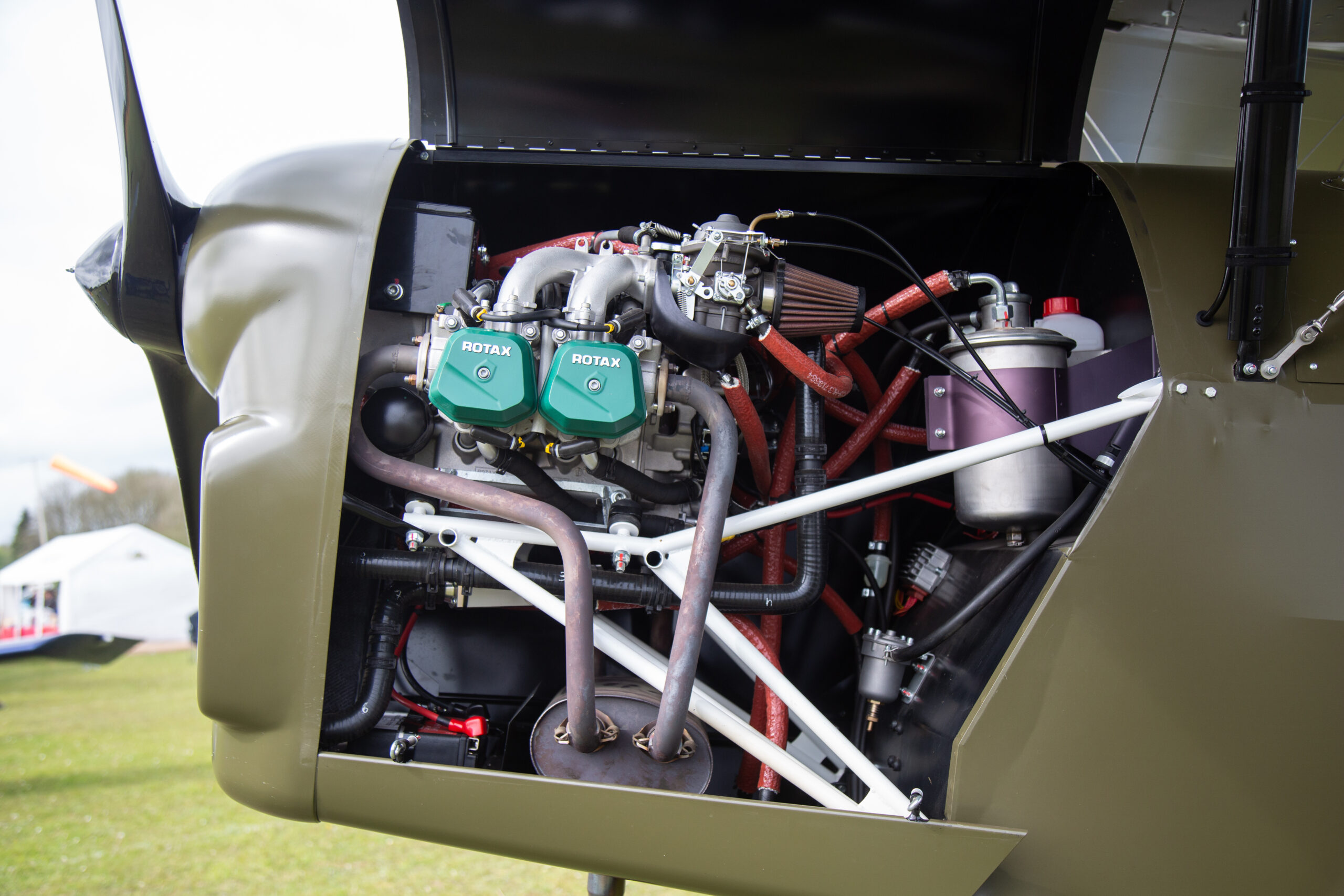

Now, the thing about most replica aircraft is that they never look quite right, and that’s where this one is different. It’s full scale—and the only obvious giveaways that it isn’t an original Stampe are the cylinder heads of the Rotax 912 protruding discreetly from the cowling. On the plus side, it’s clearly made to higher standards and with better materials than an aircraft built way back in the last century. I enjoyed a long chat with Amaury de Lacoste and Jesse Errens of Ultralight Concepts at AERO, and Amaury put me in touch with Chris Kirk at Stampe Aircraft UK, which is the UK importer. Chris introduced me to demo pilot Richard Gouble at Popham and the scene was set!

Standing on the grass at Popham, the Stampe looked completely at home—and from a distance, indiscernible from a genuine SV.4. Of course, me telling you it looks just like a Stampe is of very little use if you don’t know what a Stampe looks like, so let’s start at the spinner and commence a walk-round. Like many light aircraft designed in the 1930s, Stampes were usually powered by air-cooled inverted four-cylinder engines produced by either de Havilland or Renault. Power was typically around 130-145hp and the propeller was wood, two bladed and fixed pitch. The Stampe SV4-RS Is fitted with the ubiquitous Rotax 912ULS with 100 hp, turning a wood two-blade fixed-pitch Aerobat prop. This is the same diameter as the original DH propeller, which again adds to the authentic look.

(Photo: Brendan Digney)

Access to the engine is good, as the cowling hinges open easily on both sides.The engine’s installation is extremely neat, although as the separate oil tank is mounted quite high up I initially wondered if it might be a bit of a stretch for the shorter pilot to reach the dipstick and filler cap. As it transpired, checking the dipstick is easy, though when adding oil a small set of steps might be prudent.

Cleverly (and correctly) the large inlet for radiator cooling air is on the left side of the nose bowl, even though the Rotax rotates clockwise while de Havilland and Renault engines turn anticlockwise. (The reason the inlet is on the left on an original SV.4 is dictated by the anticlockwise rotation of the propeller, and ensures that air flows smoothly across the cylinders). I also wondered why Ultralight Concepts hadn’t completely enclosed the cylinder heads by bulging the cowling slightly, as they are the biggest clue that this machine isn’t a genuine SV.4. (Interestingly, there is at least one original SV.4 in the US powered by a Lycoming that has the cylinders protruding from the cowling).

The ballistic recovery system and all the fuel is carried in the upper wing’s center section, which is essentially an airfoil-shaped 21-gallon tank. As for the airframe, the methods and materials used in its construction are an interesting mixture. The fuselage is made from aluminum tubes connected with pop-riveted aluminum plate fittings, while the wings use tubular aluminum spars, wood for the primary ribs and a hard foam for the secondary ribs, braced with interior steel wires. The cabanes and interplane struts are in profiled steel tube, braced by external steel flying wires. As in the original (and what makes the Stampe so much better than a Tiger) there are ailerons on both the upper and lower wings. Both sets of wings have identical span and a very subtle sweepback, with just a slight stagger. The tailplane, fin, rudder and elevators are constructed in essentially the same fashion as the wings and ailerons, and everything is covered with Oratex 600.

Let’s Get Inside

(Photo: Brendan Digney)

Access to either cockpit is excellent as there are doors on both sides. For insurance reasons I had to fly from the front cockpit which, understandably, has only the most basic instruments. However, the rear cockpit is comprehensively outfitted with Kanardia instruments and Trig Avionics. Personally, I found the modern Kanardia gauges (which are both analogue and digital) a bit out of keeping with the ethos of the aircraft and would prefer the more period-looking dials that are an option. I liked the luxurious leather seats and the trim on the stick. A T-handle for the ballistic recovery system is by the pilot’s right ankle.

Now we come to one of the SV4-RS’ biggest advantages. Starting just about any vintage aeroengine is something of a ritual. With a Rotax it’s simply master and mags on and press start. I did think that perhaps the Rotax might not be sonically satisfying, and of course it doesn’t have the crisp bark of four stubby, straight-through exhaust pipes. However, it definitely isn’t as “Rotax-ey” as you might think.

Unsurprisingly the sight of this gorgeous machine starting up has drawn a small crowd to the fence and I give them a cheery confident wave and slowly taxi out in a sedate series of S-turns toward runway 26. Like most biplanes the field of view over the nose isn’t great and it is prudent to taxi at only one speed—slowly! I do not have any brakes, but the steerable tailwheel works well. Incidentally, the brakes are actuated by a pair of bicycle-type levers on the stick in the rear cockpit, and although I’ll always prefer toe brakes, I think that this installation is acceptable on this machine.

Time to Fly!

On takeoff, the acceleration is such that differential braking isn’t really required as the rudder soon bites, while on landing the touchdown speed is extremely slow. Keeping straight is easy, and a slight swing is effortlessly corrected with a dab of right rudder. Although we have 30 hp less than a stock SV.4, being considerably lighter we enjoy both a better power-to-weight ratio and a lower wing loading, and the climb rate is excellent. Forty-five knots (the ASI is in kph, but Pilot’s house style is knots) feels about right, and although the view over the nose is quite good Popham’s airspace is distinctly busy, so I weave from side-to-side to see past the nose and scan for traffic, and even this simple maneuver reveals crisp handling and well-coordinated controls.

Assessing the actual rate of climb isn’t easy as there’s no VSI, but by alternating between my watch and the altimeter I’d guess it’s at least 600 fpm. There’s a lot of traffic buzzing around, so I point the nose north to put some distance between us and Popham, before beginning my evaluation. Stampes always enjoyed an enviable reputation for fine handling and the SV4-RS doesn’t disappoint. Both the ailerons and elevators are authoritative and feel very light and smooth, being well-weighted with minimal breakout forces. All the primary controls are cable actuated.

(Photo: Brendan Digney)

Of course, a Dave Unwin flight is much more qualitative than quantitative, so let’s just say it’s a very responsive airplane that is a lot of fun to fly—because it really is! Of course, what I really wanted to do was a couple of stall turns and then a three-turn spin, followed by a loop and a barrel roll. Sadly, none of those maneuvers are currently permitted in any microlight, for now. There are certainly no structural limits on the airframe that preclude aerobatics, as it’s stressed to +4.7/-2.5 G at max weight. Flown solo with half fuel I bet it’d be good for +6/-3. And now, a confession. The next item on the flight test card after “control” is “stability,” but I was having so much fun that I completely forgot! Mea culpa, and anyway, this machine is all about flying, open cockpit flying—real flying!

I always like to know what the handling is like at the slow side of the speed spectrum before flying circuits, so I try a couple of stalls. This produces no real surprises, and the stall is as slow as I’d expected with such a low wing loading. Indeed, if the speed was reduced at a steady one knot per second—with the slip ball centered and the nose just above the horizon—there wasn’t really what I would call a classic stall. Instead, it simply sinks straight ahead with a gentle airframe buffet and a high sink rate at about 35 knots. A more vigorous approach, with the nose held way above the horizon and the speed reduced more quickly, provoked it into reluctantly dropping its nose and a wing. Recovery was easy and immediate.

Cruising back toward Popham demonstrates the inherent truth behind the well-known aeronautical observation that ‘the drag goes up with the square of the speed’. A comfortable cruise speed is around 70 knots IAS, and this requires about 4800 rpm (75% power—which Richard had to set as there’s no tachometer in the front cockpit) while burning about 5 gph. Put the spurs to it (max continuous is 5500) and you’ll burn at least 25% more fuel for a 12% increase in speed! But why would you do that anyway? Aircraft like this are much more about the journey than the destination.

Back at Popham

(Photo: Brendan Digney)

Overhead the airfield the windsock shows that the wind has backed slightly, although not enough to make life difficult. Proceeding downwind in an orderly fashion for runway 26 I wait until the wingtip appears to be almost touching the threshold, then throttle slowly back, trim for 50, pause and then turn. More by luck than judgment, a nicely curved continuous base-onto-final turn produces a near-perfect ‘constant aspect’ approach, and I add just a hint of power halfway around to shift the aiming point slightly further into the field. The field of view is acceptable (it is a biplane after all, with that configuration’s inherent limitations) and as we come “around the corner” it feels nicely speed-stable. I’ve stayed deliberately high so that I can slip off the excess height on final as this will ensure I don’t lose sight of the runway.

Over the hedge! Stick and throttle smoothly back together (the throttle is almost closed anyway) and the Stampe settles slightly, the wheels feeling for the ground. Now, I’d been watching Richard’s landings, and noted he tended to wheel it on. However, on grass I prefer a three-pointer, and I tell Richard this is my intent. What I should have done is ask him why he was wheeling it on! Anyway, everything feels perfect and I keep easing the stick back…back…back. All three wheels touch together, but the lightly-loaded wings are still thick with lift and we skip back into the sky. I’ve done enough taildragging to know that the trick here is to just hold what you have and let it settle, but to my chagrin it bounce and bounces—and bounces again! I suspect it’s one of those landings that feels worse than it looks (nothing fell off)—but it feels pretty bad!

It was never dangerous and Richard didn’t intervene—but definitely “sub-optimum”! I’m mortified, but Richard just chuckles as I convert our untidy arrival into a ‘touch ‘n’ go’. Downwind again, this time for runway 21, and I’m determined to get it right, although Richard’s preference for wheel landings has failed to permeate my brain. This time I slip to the left (it slips beautifully) and rudder it straight on very short final. I guess the speed was probably around 50 knots but I didn’t even look at the ASI—you can feel the speed through the stick and hear it through the airflow. All three wheels are practically brushing the tips of the grass and I wait for the subtle and seamless transference of weight from wing to wheel. There’s that fleeting, floating moment as the last of the lift leaves the wings, the aircraft settles, the tires rumble gently across the grass then boing! Up we go again, albeit not as bad as the first one, and after a little hop, skip and a jump it stays down and rolls out straight and true, over quite a short run.

Of course, we all know landing on grass greatly deskills the taildragger, but nevertheless as the speed drops I remain ready for a swing that doesn’t come. (Interestingly, I spoke to a spectator later, who claimed that it all looked perfectly fine.) I subsequently discussed this with Amaury, who allowed that the test aircraft was a very new machine, and that the undercarriage rubbers hadn’t quite bedded in yet or might need adjusting. It certainly seemed to me that it wasn’t as well damped as I’d like). I could have literally spent the next hour just doing touch and goes (and not just because I still haven’t got a good landing) because to my mind there’s a few finer things than a well flown approach that culminates in a smooth landing—and that’s triply true in an open-cockpit biplane at a grass field. However, I know there is still quite a few people waiting to sample this machine and so with a great deal of reluctance, taxi it back. There’s still a sizeable crowd by the fence, and I can almost hear the click of the myriad camera shutters, above the growl of the engine. It’s not loud, but it’s not quite Rotax if you know what I mean.

To conclude, I loved it—and if I had any money I’d buy one. It looks good, flies great and even sounds quite convincing. Of course, it’s a fair bit more expensive than a genuine one—but they’re collectors’ items—and we’ve already ascertained why they’re called that. The maintenance on an original SV.4 must be horrendous!

I own an original SV4 with a Lycoming 0320 conversion (exposed cylinders) and it is an absolute joy to fly and the easiest tail dragger to land I have ever flown. I visited the SV-RS factory in Belgium this past summer and those guys could not be nicer. If they can get this aircraft into the US market I think it will be a huge success.

Buddy just removed the Renault engine from a restored SV4 last weekend. Shipping his 2 Renaults to a group in Iceland that put a rod through the side of their engine. Picked up a new mount and cowl at OSH to install a Lycoming O-360 on his SV4 and we have spare stripped down SV4. Renault ran good, he just wanted to have a more familiar engine and an electric starter, air starter could be finicky,

I have flown an original SV4 in the (past); loved this aircraft all my life. Thanks, Stampe and Vertogen!