(Photo: AOPA)

In the previous article, I explained how high levels of flight activity can make access more affordable and, for most people, how that would likely be achieved only through some form of shared ownership/use. The use of the term “shared ownership/use” is deliberate because not everybody really wants or feels the need to “own” something they use but, perhaps, believes that there is no other realistic or safe alternative.

This article is based on a close examination of the reasons people give for not being open to any form of sharing and looking at how those barriers might be removed. It will also try to address the second, less discussed, part of affordability, which is “accessibility” to shared use aircraft. There is little benefit to being able to afford what does not, essentially, exist. A good, but somewhat parallel, example of this has been the original iteration of Light Sport Aircraft and Sport Pilot Licenses. Both had huge potential to improve affordability of learning to fly and then being able to continue afterwards, but, widespread accessibility and, dare I say it, acceptability, was never achieved. My article on MOSAIC, referenced this so I am not going to repeat that here, other than to say that if, as hoped, we see a substantial growth in the makes and models of models designed under the new standards allowed by MOSAIC, they could be the perfect conduit for the type of expansion of accessibility, safety, technology and affordability people are seeking.

When it comes to shared ownership/use, both AOPA (Flying Clubs – You Can Fly) and EAA (Flying Club Resource Center) offer great resources on how to find, set-up and manage flight clubs, partnerships etc. Indeed, using their guides and explanations should be very high on everybody’s list of first steps when it comes to exploring these options.

Looking at the different clubs out there, it becomes clear that there is a wide variety of purposes and motivations behind each of them. Sometimes it springs from an individual who has a plane and simply wants to spread out the costs of operation with a few new friends and other times it involves clubs that have professional management, decades of experience and tens of planes available to hundreds of members. The point being, that while the mechanisms to create and manage clubs is very well covered by AOPA and EAA there is really no coordination at state, regional or national levels so the net result is a somewhat random.

The EAA, via Timm Bogenhagen, Member Programs Specialist, reports about 100 clubs with many of them near to EAA Chapters. They do not have hard statistics for members and numbers of aircraft but estimate one to two aircraft per club and 20-30 members per club.

Without solid statistics, we have to resort to making assumptions. It is probable, if not provable, that between AOPA and EAA they have captured at least 50% of all the shared ownership/use groups in the USA. Their combined total comes to about 1200 groups, so, if we double that based on the percentage of clubs linked to one or both organizations, we get to approximately 2400 groups with an average of two planes per group so, perhaps 4800 aircraft in some form of shared use excluding flight schools. Based on the 2022 FAA GA survey data, that would suggest that less than 4% of the aircraft designated as “Personal” (141,600) in the survey are in any form of shared use. Consequently, given the average hours per aircraft flown of 58 quoted in the first part of this article, it would not be a stretch to conclude that the overwhelming majority of personal planes are not providing their owners with cost efficient flying.

Well established, and geographically limited clubs confirm emphatically both the favorable economics of sharing through volume but, with such limited penetration, clearly have not established a universally winning model of success. AOPA and EAA have contributed valuable insights and assistance to already motivated people on how to create and run such clubs, but widespread adoption has possibly been held back by the lack of a “for profit” business model. Owning and operating high volume aircraft requires investment, infrastructure, management, experience and continuity that often goes beyond the realm of voluntary organizations. The profit motive may well be what is needed to take shared ownership to the next level but, entrepreneurs and their money like to see clearly defined markets with standards that can be met. At the present time there is neither a clearly defined market nor a clearly defined path to reach customers.

What role does standardization play?

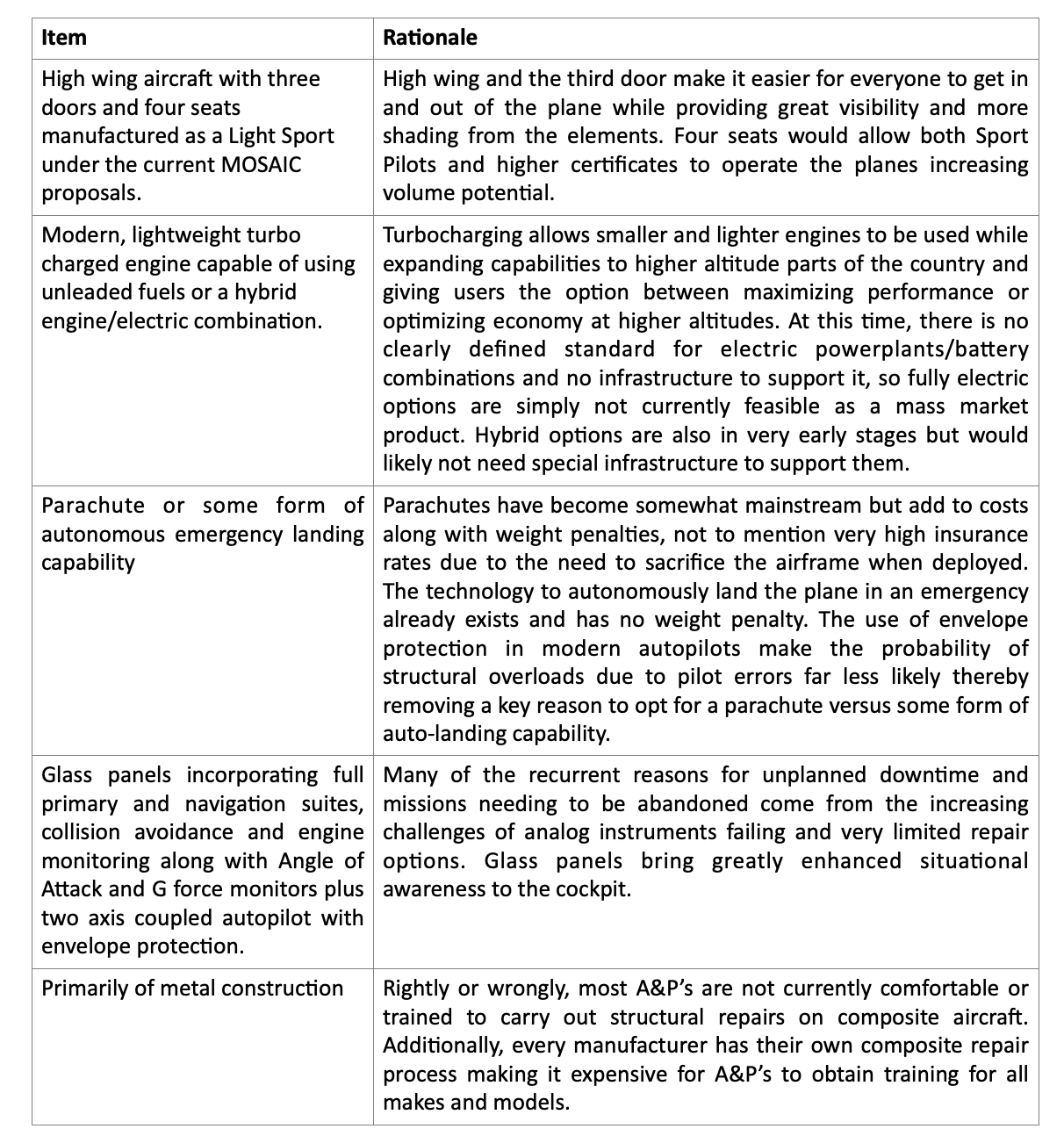

In the first article, the emphasis was on making the case for how effective high volume of activity is in bringing down costs. However, there are clearly other factors that should also be considered when trying to create a sustainable business model. Possibly, the most important of those factors is the choice of aircraft. Current shared ownership/use aircraft likely encompass a very wide range of makes and models, ages, condition, capabilities and installed equipment. The beauty of this is that pilots can, at least in theory, align their desires and budgets with specific local options. A key practical downside is that the “dating process” between pilots and available options means that few “marriages” actually result for a variety of reasons. This takes us to the thorny question of whether trying to create a standardized offering (i.e., combination of aircraft and access to those aircraft) could open up opportunities, or simply lead to more disagreements over personal preferences. The balance of the discussion here will be that, in addition to volume and a profit motive, creating a standardized offering is essential if progress is to be made. The combination of all these three factors would go a very long way toward removing the barriers of acceptability that can be cited as reasons not to share, and that were explored in the first article.

By not having a defined standard for aircraft or how the planes are managed, prospective users/owners are faced with having to make a wide range of decisions without necessarily having the skills or experience to sort through them meaningfully. This complexity and the high risk of making a “bad” choice undoubtedly has some effect on whether people even start on the process, let alone, complete it. This is where MOSAIC comes into the equation because it is an entirely standards-based process when it comes to the proposed new Light Sport definitions covering both aircraft and Sport Pilot privileges. Additionally, it opens up the option for four-seat planes to everyone including Sport Pilots and allows manufacturers to use the ATSM’s standards to bring down their costs and adopt new technology.

Taking this to its next logical step would be to have a standard for shared ownership/use aircraft that clubs, or entrepreneurs, could operate to. For example, one such offering might be presented as follows with a goal of covering as many prospective needs as possible.

The challenge with all of the above is that it does not really provide a clear path forward or even a vision as to what might be. A possible description of how the future could look is presented below as a catalyst to generate ideas and not as an exact prescription for success.

So, lets dream and look five to 10 years into the future:

- The final version of MOSAIC has been implemented and this has generated a wide variety of new models being offered into the market at significantly lower price points than the legacy and semi legacy companies of today. They take maximum advantage of the standards based processes and benefit from avionics and engines that meet those standards.

- Local, regional and national entities have signed up to a franchise model offering only one make and model of shared use plane enabling a chosen manufacturer to produce large volumes efficiently and cost effectively. This has flow through effects on all the suppliers who can also benefit from longer product runs and improved component reliability.\

- There are four parts to the distribution chain:

- The provider who rents/manages the shared use fleets. They access the aircraft via leases rather than direct purchases. They follow a standard model for management of the aircraft, insurance protocols, currency of users, scheduling, maintenance etc using a franchise type process.

- Leasing companies buy the aircraft from the manufacturer and lease them to the providers. Their key role is to try and balance the supply of aircraft with demand and work directly with the chosen manufacturer on support, spare parts etc.

- Individual or corporate investors lend to and/or invest in the leasing companies but do not take any active management role. The only difference between these investors and others is that they have explicitly bought into and support the concept on a macro level rather than seeing each aircraft purchase as a new investment. This creates a far more fluid and cost-effective process by cutting down on duplicative bureaucracy.

- The aircraft manufacturer has committed to a standard product and very competitive pricing knowing that they can expect certain volumes of aircraft on an ongoing basis.

- Flights schools have also bought into the concept of an affordable standard product for their training operations making the transition for graduating students into the shared use fleet seamless.

- Pilots can sign up at the local level and be approved to use the standard aircraft model with varying levels of commitment while benefiting from lower prices than traditional rental options and no administrative or ownership burdens. In many cases their provider would also be the local flight school or FBO. Being well equipped, professionally managed and full of technology has gone a long way towards the removal of many barriers to people’s willingness to share.

- Average flight hours per active aircraft are up twenty-fold contributing both to more affordable flying while offering everyone in the chain a good profit potential.

- More pilots are active and current which, when combined with access to modern aircraft, has created a far safer operating environment for all.

- The planes remaining in personal ownership tend to be more specialist and higher end.

In summary, bringing costs down to “affordable” levels depends on finding ways to scale up hours flown per aircraft, accepting the concept of a standard product and being open to using planes that are professionally managed, maintained and owned by others. Some, but not all, of the elements needed to make this a reality already exist. The biggest challenge will be to convince people that it is possible to reshape the way access to planes is managed. Trying to reverse the trend of increasingly expensive planes that leave the majority of pilots scrabbling for 50 year old hand-me-downs is not going to happen without disturbing a lot of established industry customs and practices, so will likely face stiff opposition.

Leave a Reply