IN FLIGHT = PC-Aero’s Elektra One can be flown for 3 hours without noise and with lower operation costs than conventionally powered aircraft.

– COPYRIGHT JEAN-MARIE URLACHER INFO-PILOTE.JPG

CLEAN & SIMPLE – Randall Fishman’s third generation electric aircraft is neat

and clean as befits such an aircraft. Naturally, electronic instruments are featured

MOTORGLIDER DESIGN – Looking very European – but most definitely an

American design through and through – the ElectraFlyer-X has the smooth lines of a

motorglider.

AIR SLIPPER – Only in an electric-powered aircraft (other than one with the engine

in the rear transmitting to the nose) could the cowling aft of the prop be so small.

MORE NEEDED? – If you’re used to looking at a tachometer

and fuel gauge, these instruments may look foreign, but you

might want to get used to them as electric continues to invade

aviation.

GERMAN ENGINEERING – The Elektra One uses a modern

composite glass and carbon structure, a single, retractable

main wheel, and is said to have a propeller efficiency of 90%

driven by a highly efficient electric drive.

– COPYRIGHT JEAN-MARIE URLACHER INFO-PILOTE.JPG

ELECTRA PRINCE — Prince Albert of Monaco made an appearance at Aero in conjunction

with the electric aircraft prizes. He took a seat in the Elektra One as

designer Calin Gologan (in striped tie) explains the concept.

ELECTRIC DESIGNER – The long, tall designer of the award-winning Elektra

One is Calin Gologan. Note the single main landing wheel, which can be retracted.

FORMATION FLIGHT? – In this photos it appears a solitary engine nacelle has somehow taxied up between two

Taurus motorgliders, but this one-off G4 airplane was built to win a prize, a big prize.

GRACEFUL JUICER – Electric power outperforms its gasoline-powered counterpart in Pipistrel’s Taurus

Electro G2 motorglider.

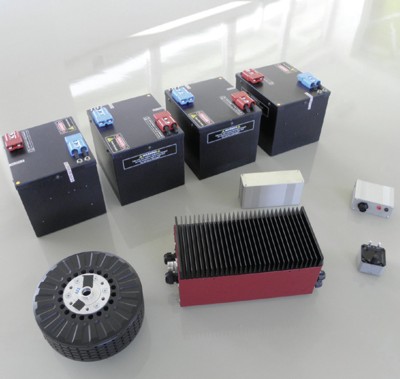

BATTERY POWER – Batteries stand in the rear row

with the motor to the left and controller elements in

the lower right. All these parts have been assembled

or designed by Pipistrel for their several electric aircraft

entries.

SOLAR TRAILER – After flying your eTaurus, put it in its traveling hangar

and, presto, the trailer will charge your airplane’s batteries, essentially for

free (after acquisition costs are paid, of course). How cool is that?

VEE-TAILED – Is it any wonder Yuneec’s sleek e430 attracted crowds every day when it first appeared at AirVenture?

LIGHT TAKEOFF – With its 45-foot wingspan, the e430 can take off in 265 feet, climb at 1,320 fpm, cruise at

55 mph, and has a glide ratio of 25:1.

ELECTRIC TRIKE – Yuneec’s tiny little trike with an even tinier motor flies under a high-performance La

Mouette hang glider wing.

Energy Density Primer

Composite Fuselage as “Batteries?”

Winning the LEAP

and Berblinger Prize

LEAN LINES – A studio image reveals the lean lines of the e430 and its gentle curves throughout the design.

Flying with Juice

As an airplane approaches, a whirring sound accompanied by a

barely discernible whine and a mild propeller buzz exhibit a

Doppler effect as the plane passes overhead. What is that curious noise?

We are intimately attuned to internal combustion engine sounds –

some experts claim they can identify the brand and size of an engine

simply by listening to it run. We’re less aware of electric motor noises

because we quickly tune them out. Electric motors run everywhere in

our lives – in our refrigerators, our computers, in our ceiling fans, and

numerous other appliances. Most motors – it’s incorrect to call them an

“engine” – are exceptionally quiet, and that’s a good thing.

One wonders if relatively quiet electric motors on aircraft will invade

our piston-powered world, especially given noise sensitivity at many airports.

Some say, “We’re about to see if electric works.” I say, “We’re seeing

it right now!”

Two years ago, I wrote about ultralights – literally Part 103-compliant

ultralights – operating remarkably well on electric power.1 In the ensuing

months, more projects have been announced. With a whole issue of

Light Sport and Ultralight Flying we might cover the entire field. To

give a picture of the state of development, I’ll update coverage of four

aircraft including projects from two of the original players.

Our four include the ElectraFlyer X, a ground-up new design from

electric power pioneer Randall Fishman; the prize-winning Electra One,

Light Sport and Ultralight Flying Pilot’s Report

a nifty single-seater with a retractable single main wheel; the Pipistrel

Taurus and variations on the theme from a company moving fast; and

several projects from the prolific Shanghai company, Yuneec. The electric

phenomenon is global. Our examples hail from USA, Germany, Slovenia,

and China.

ELECTRAFLYER ELECTRIC AIRPLANES

Our first example is first in other ways. Randall Fishman brought a product, not

simply to airshows but to market way back in ’07. In electric airplane terms – much

like “Internet time” – it seems like ancient history since airshow visitors saw his

ElectraFlyer Trike. Fishman has stayed active in the game with two follow-on developments,

though the real story may be the way his company can supply electric

propulsion hardware to builders of any airplane.

His subsequent single-seat ElectraFlyer-C, essentially a modified Moni motorglider,

can fly under power for up to 90 minutes (or 60 minutes if landing with the equivalent

of a legal, day VFR fuel reserve). A portable 110-volt charger can recharge the

batteries in about 6 hours.A more powerful 220-volt charger can do the job in 2 hours

if a suitable outlet is available. Estimated “fuel” cost for such a flight is less than 75

cents, Fishman reports.

Batteries could last 10 years, assuming typical use and recharge cycles. Given a

power supply cost at about $7,500, that’s $750 per year plus recharges, call it $1,000

even. At $4 per gallon, that’s 250 gallons worth and at 5 gallons per hour, that’s 50

hours of flying per year. Any greater amount of annual flying is almost free because

you’ve already covered the cost of the batteries. In a combustion engine aircraft, you

would have to keep buying your favorite fossil fuel.

Having worked out the specs and issues with his Trike and ElectraFlyer-C,

Fishman is completing work on an original 2-seat development, the ElectraFlyer-X.

The beautiful new model has a smooth motorglider look with a high-aspect-ratio

wing powered by Fishman’s proprietary 50-hp motor, motor controller, and battery

solution. For the record, both his ElectraFlyer Trike and the C flew on 28 horsepower.

“The ElectraFlyer-X cruises at 80 mph and has a top speed in straight and level

flight of 100 mph,” reports Fishman. “At the slower speed, duration is 1.5 to 2 hours.”

Fishman’s electric motor reliably starts up instantly. The electric powerplant barely

vibrates and you needn’t contend with smelly fuel or oil. Other than prop noise,

the Fishman system is quiet.

Until the ElectraFlyer-X comes to market, you can buy,

today, an ElectraFlyer Trike for about $20,000 for trike, wing,

and batteries with a 45-minute duration. Prices change, so

check with Fishman’s Electric Aircraft Corporation for the latest

information. At press time, the Moni-based ready-to-fly

ElectraFlyer-C was for sale at less than $50,000. This is a oneoff

design, so you should act soon if interested.

For more detailed specifications and info, contact:

Electric Aircraft Corporation 118 Pine Street, Suite 3,

Cliffside Park, NJ 07010. Phone: 561.351.1190 | e-mail:

randall@electraflyer.com | Internet: www.electraflyer.com.

ELEKTRA ONE FROM PC-AERO

Our next example reveals quality German engineering. For

that and its innovations, Elektra One shared in the Lindbergh

prize (see the “Winning the Berblinger Prize and LEAP” sidebar)

awarded in April at the European Aero 2011 event.

Elektra One was designed by PC-Aero. “Using existing technology,

it is possible to fly with a 1- and a 2-seat aircraft without

CO2 emission for more than 3 hours, without noise and for lower

operation costs in comparison with conventionally powered aircraft,”

says Calin Gologan, president of PC-Aero. “This is the

future of leisure aviation as a bridge to the next step: electric

transportation.”

Romanian aeronautical engineer Gologan reports several

advantages of electric powerplants for light aircraft (and these

apply to any electric-powered aircraft): environmental protection

through elimination of CO2 emissions; low noise; long range

(depending on how much battery can be carried); low operating

costs.

Gologan expects to achieve more than 3 hours

flight time, delivering more than a 250-mile range.

He thinks cruise can hit 100 mph (a figure supported

by Fishman’s experience). Noise generated is significantly

restrained in cruise by keeping the propeller

speed at 1,400 rpm.

The developer predicts emission-free flying and

sees environmentally sound machines drawing little

grid power by using solar panels on the hangar for

very low cost recharging. (Also see photo of Pipistrel’s

rolling solar hangar that makes a similar claim.)

PC-Aero’s goal is a total system of aircraft, hangar,

and power selling for less than |100,000 (about

$142,604). Remember, this includes the cost of

hangar and “fuel.”

According to the manufacturer, here are a few specifications

of the single-seat Elektra One: maximum

weight 660 pounds; 28-foot wingspan; maximum

engine power 16 kW (21 hp); empty weight (without

batteries) 220 pounds; maximum battery weight 220

pounds; payload 220 pounds.

The magic isn’t solely the powerplant. The innovative

Elektra One uses a modern composite glass and

carbon structure, and a single, retractable main

wheel. Gologan says the Elektra One has an

advanced aerodynamic design and propeller efficiency

of 90% driven by a highly efficient electric drive.

Addressing media at his PC-Aero company’s booth

at Aero 2011, Gologan explained that he began work

on the Elektra One three years ago with the goal of

optimizing it as a cruising machine. Reportedly this

is why he gave the airplane a relatively short 28-foot

wingspan. Elektra One’s wing has a unique profile,

with a half-span sweep and some remarkable characteristics.

“Test flying showed that I had developed a

highly tolerant wing profile,” says Gologan. “It can fly

at angles of attack as high as 40°, where you can still

use the ailerons and still not stall. The wing also provides

good gliding characteristics shown by a 25:1

glide ratio.”

Power for the first Elektra One was supplied by a

13.5-kilowatt (about 18-hp) electric motor built by

Geiger Engineering, which also makes Elektra One’s

propeller and battery controller. The airplane has a

single, manually retractable landing gear, two small

wingtip wheels, and a variable-pitch propeller.

Gologan claims the Elektra One is only 20% as noisy

as a typical general aviation airplane. He said it

would cost just $49 per hour to operate.

The Elektra One will be certified under Germany’s

ultralight regulations; a 2-seater is in the works.

Certification of the larger model “will not be a problem,

because for years my work was as a certification

engineer,” Gologan says. He expects certification by

the end of 2011. His ultimate goal is a family of electrically

powered airplanes. Principally a designer and

engineer, Gologan’s plan is to hand marketing and

sales duties to NeoWings, a firm based in Augsburg,

Germany.

For more detailed specifications and info, contact:

PC-Aero, Buchenweg 3, 87484 Nesselwang,

Germany. E-mail: calin.gologan@pc-aero.de |

Internet: www.pc-aero.de.

PIPISTREL’S PROJECTS

When I finally met Pipistrel designer Tine Tomazic,

the engineer seemed highly confident in his work.

Tomazic works closely with Ivo Boscarol, general

manager and founder of Pipistrel. Perhaps the company’s

assuredness is justified, since it’s already a big

NASA efficiency competition winner to the tune of

$165,000. No wonder Pipistrel has created the

unusual G4 (see photo) for the 2011 NASA/CAFE

prize of $1.65 million.

“Can electric perform better than conventional

powerplants?” asked Tomazic during a presentation.

“Absolutely!” he said, answering his own question.

Tomazic’s enthusiasm is infectious.

Indeed, Pipistrel is underway with a very impressive

4-seater called Panthera that is proposed to fly

200 mph on a combustion engine, a hybrid engine, or

an all-electric version. For most companies such

claims would sound boastful. Pipistrel might pull it

off. Their Taurus Electro G2 is already for sale and

performing well with electric-only power.

As Tomazic puts it, “For the first time electric

power outperforms its gasoline-powered counterpart

in our Taurus.” He observes that the Taurus

Electro G2 can use a shorter runway, climbs faster

and performs much better than the gasoline-powered

version when it comes to high altitude operations.

All this is possible, thanks to the specially

developed emission-free Pipistrel 40kW electric

power train.

Of course, G2 – a motorglider – is a specialty aircraft

and perhaps electric power will not outperform

a combustion engine in, for example, the Bye

Aerospace electric power conversion of a Cessna

172 Skyhawk. Pipistrel’s airplanes are far sleeker

and lighter for their mission than the dated Cessna

design.

Pipistrel’s custom-developed Lithium batteries

come in two configurations, capable of launching

the Taurus to 4,000 feet or 6,500 feet respectively.

Remember, this is a self-launching sailplane; getting

to an altitude where soaring lift can be found is

the whole point. The batteries are monitored constantly

by Pipistrel’s own battery management system

complete with data logging and battery health

forecasting.

The Taurus’ electric motor weighs only 24 pounds

while developing the equivalent of 54 horsepower.

As Pipistrel’s designers upped the power of their

propulsion unit, they also developed a new propeller,

which they believe has increased efficiency.

Pipistrel has also invented a new set of onboard,

networked avionics that provides a “fly-by-wire

power train management with built-in multi-layer

protection logic,” says the company. Engineers add,

“This represents a great improvement over the system

used in the Taurus Electro prototype, where

everything was handled by the pilot.”

Pipistrel has been pushing the envelope and feels

they have achieved “the absolute pinnacle of today’s

battery technology, combining low weight, high

power and high energy density to levels that

seemed impossible as recently as ’09.” When a battery

cell is performing poorly, the system is able to

signal the need for maintenance.

The proof of Pipistrel’s admirable engineering

may reveal itself at the NASA/CAFE Challenge in

July ’11.

For more detailed specifications and info, contact:

Pipistrel Aircraft, Gori_ka cesta 50a SI-5270

Ajdovina, Slovenia. Phone: 213.984.1237 | e-mail:

info@pipistrel-usa.com |Internet: www.pipistrelusa.com

YUNEEC’S DEVELOPMENTS

Huge amounts of media and public attention

were focused on Yuneec’s smooth, handsome e430 at

AirVenture in the summer of ’09. The 2-seater took

Oshkosh by storm. It appeared practical and workable,

though it isn’t on the market at this time.

“With the e430’s flight times of between 1.5 and 3

hours (depending on configuration), electric flight

now becomes a realistic power source for sport aviation,”

says Yuneec engineers. “Charging times of 3

hours for as little as $5 make electric a genuinely

low-cost way to fly, and with only two main moving

parts in the motor (the bearings), the reliability and maintenance

are like nothing seen before.”

Use of a 6-battery setup in e430 results in 1.5 to 2 hours

of flight and with such an installation, payload remains a

respectable 400 pounds even with a 45-foot wing span. The

long wings ensure efficient electric cruising while adding a

safety factor. Yuneec says a 10-battery setup could fly 2.25

to 2.5 hours, though the up-front investment would be significantly

higher. The rub in electric aircraft is concentrated

in the purchase cost of batteries plus their weight. It is

in this area that development is needed so it’s fortunate for

aviation that auto companies are spending billions in parallel

development. The good news is that electric airplane

developers can take advantage of battery technology

improvements as they arrive.

A 45-foot wingspan gives the e430 a 25:1 glide ratio and

flight tests produced these results: Takeoff in 265 feet at 40

mph; climb rate 1,320 fpm; cruise speed 55 mph; top speed

level flight 93 mph.

As initially developed by Flightstar in the USA, the e-

Spyder took its first flight in July ’09. Yuneec supplied the

eSpyder’s electric power. Flightstar initially mounted the

twin lithium polymer battery packs on either side of the

design’s robust main fuselage tube, though they were subsequently

hidden in a slide-out drawer under the cockpit

floor pan, an excellent location for several reasons.

Flightstar’s stateside experience realized electric

motors are user-friendlier in nearly every

way, but a pilot would have some new learning

to do. For example, experts advise never allowing

lithium polymer batteries to drain completely.

Fortunately, the Yuneec controlling hardware

installed on the eSpyder provides warning systems

to help you manage this task.

Yuneec and Flightstar say batteries will last

for at least 500 cycle charges and Yuneec says

this equates to more than 250 hours of flying.

That many hours with a Rotax 912 would cost

about $5,000 in fuel alone, plus oil, spark plugs,

overhaul costs and more. So, as we’ve seen with

some other entries, batteries for electric motors

represent a similar net flying cost as a gas

engine with fuel, but without the noise, smell, or

mess.

For more detailed specifications and info, contact:

Yuneec International Ltd., 388 Zhengwei

Road, Jinxi Town, Kunshan, Jiangsu, China.

Phone: 011.86.512.5012.1243

| Fax: 011-86-512-5012-1255 | e-mail:

sales@yuneec.com | Internet: yuneeccouk.site.securepod.com/index.

THE END OF ELECTRIC?

This may be the end of this article, but it won’t

be my last about electric airplanes. I will create

an entire section about electric motor aircraft on

my Website: www.ByDanJohnson.com . Batterypowered

airplanes are in their infancy, but we

will all be hearing much more about this idea as

fuel prices continue their inexorable rise.

An electric airplane could be in your future –

and for less cost than you might think. With or

without your purchase, electrics will most

assuredly be sharing our skies. Listen for them!

1See “Pilot Report: Electric Aeroplanes,”

September ’09 Light Sport and Ultralight Flying

magazine.

Leave a Reply