One year ago,

aviation experienced

a tectonic

plate change.

On the exact

day that Neil

Armstrong first

set foot on the

moon 35 years

earlier, the

Federal Aviation

Administration

(FAA) released

a new regulation-

known as

the sport pilot/

light-sport aircraft

rule, or its

abbreviation, SP/

LSA-that represents

the biggest

change in aviation

in 50 years.

If you’ve been fascinated

with flying or

seek a new adventure,

the sport pilot

certificate and new

light-sport aircraft

may be your ticket

to a glorious form of

three-dimensional

freedom.

For More Information

What Sport Pilots Can Fly

Sport pilots can fly six categories of aircraft as shown here. Included in this graphic is the minimum number of training

hours required to earn a sport pilot certificate in that category. Note: Your instructor may suggest more training, if needed,

before recommending you to take your sport pilot tests.

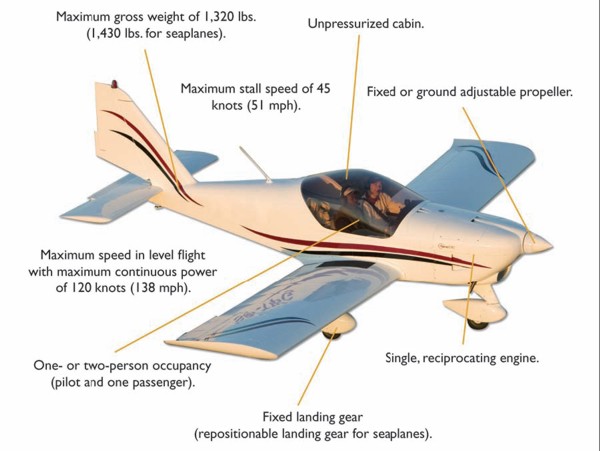

What Defines a Light-Sport Aircraft?

The FAA has defined a light-sport aircraft as any easy-to-fly aircraft that, since its initial certification, has continued

to meet the following performance parameters.

Sport pilot and light-sport aircraft,

what’s it all about?

If you’ve ever thought about

learning to fly, returning to

flying, or resuming flying lessons

that you started years ago,

congratulations; your timing is

just about perfect! This rule provides

new opportunities for you as well as

anyone who has dreamed of owning

an aircraft.

This article will summarize how

SP/LSA affects you. We’ll keep it simple;

when you’re ready for more,

EAA offers many ways to become

more informed (see “For More

Information”). Like many activities,

flying has its own language with

abbreviations, acronyms, forms, and

numbers to make discussing it faster.

Veteran pilots throw this lingo around

casually and often baffle those who

aren’t involved. We’ll avoid such jargon

in this article, and we’ll only use

abbreviations after we’ve explained

them.

Let’s Get Started!

SP/LSA has two basic components:

“Sport pilot” refers to a new pilot

certificate you can earn (the FAA calls

them certificates as opposed to licenses);

“Light-sport aircraft (LSA)” refers

to a new category of aircraft. Any

certificated pilot can fly an LSA, but

sport pilots can only fly aircraft that

meet the definition of an LSA. (See

“What Is a Light-Sport Aircraft?”)

We’ll talk about these two pieces

of the SP/LSA pie separately even

though they are deeply intertwined.

We will also give you the “tip of the

iceberg” view, as drilling down for

the other 90 percent takes time and

gets into aviation phrases that may

not be readily understandable. Again,

that’s where EAA’s resources can assist

you. (See “For More Information.”)

The SP/LSA regulation is wide

ranging. You may encounter current

pilots and even FAA personnel who

don’t understand it well or perhaps

misunderstand some of the details.

Other FAA regulations have numbers

like Part 91, Part 61, and Part

103 but not SP/LSA. It alters many

existing regulations, and in so doing,

SP/LSA has thrown a curve to many

experienced aviators who thought

they “knew the rules.” New pilots, however, don’t have to unlearn and

relearn. Therefore, new or returning

pilots may get up to speed quicker

than some experts, and that’s a nice

aspect of SP/LSA.

The Sport Pilot Certificate

Earning a sport pilot certificate

is akin to taking driver’s education.

You learn some basic information

and the “rules of the road,” practice

some skills with an instructor for a

defined number of hours, and get

approved to fly by yourself for a few

more hours|that’s called solo flying.

Then, when your instructor feels you

are competent, you make final preparations

to take two tests: a knowledge

test, which the FAA administers via

computer by two national testing

agencies, and a practical test, which

involves flying with an examiner and

demonstrating the skills required of

sport pilots as well answering some

questions the examiner will ask in

a verbal exam. Most pilots refer to

these as the written, oral, and flight

tests.

One of the benefits of the sport

pilot regulation is that it doesn’t require you to learn lots of difficult

tasks you won’t encounter in

your typical flying. Your training to

become a sport pilot will involve

learning the basic skills and safety

practices needed to fly for fun in

pleasant weather. You’ll fly in the

daytime with only one other occupant

at slower speeds, commonly

thought to be safer. You’ll learn to fly

a simple airplane in simple airspace.

More training is logically required of

a private pilot who’s allowed to fly an

aircraft with an unrestricted number

of occupants at higher speeds into

areas of higher air traffic congestion

in varying weather conditions.

Once you have your sport pilot

certificate, you can add additional

skills that will earn you more flying

privileges. To gain these added skills

you’ll need to spend a few more hours

training with an instructor. When

your instructor is confident you’ve

attained the required skill level, he

or she will sign your logbook-the

book where all your flight lessons

and flight time is recorded-signifying

you have earned this privilege.

You do not have to take any further

tests. That’s a big difference between

the sport pilot certificate and other

pilot certificates.

For example, let’s say you learned

to fly at a small private airstrip that

didn’t require radio communications.

Then, after you became more

confident in your flying skills, you

decided you want to venture to airports

that do require radio communication.

To add that privilege, you

would spend some time flying with

your instructor to gain the necessary

radio skills. When your instructor is

satisfied you’ve mastered that skill,

he or she will simply endorse your

logbook noting that you now have

that privilege.

You can also earn the privilege

to fly a different type of aircraft

than the one in which you originally

trained|for example, a powered

parachute instead of a fixedwing

airplane. The process to add a

new aircraft type to your sport pilot

privileges is also simple: fly with an instructor to gain the skills for this

new category of aircraft, and then

take a proficiency flight with a different

instructor. No further knowledge

or practical test is required.

There’s a wide variety of LSA available

to choose from. The diversity in

LSA is breathtaking and offers new

experiences for almost any aviator.

Lower Cost for Beginners

One of the best features of SP/LSA

is that it can dramatically lower the

cost to learn to fly. Most estimates for

earning a private pilot certificate suggest

the cost can run between $5,000

to $7,000 or more. For sport pilots,

the cost can range from $1,500 to

$2,500 or more, depending on the

category of aircraft in which you

learn to fly and where you live.

For example, if you learn to fly in

powered parachutes, which require

a minimum of 12 hours of training,

the cost could be less than $1,000 for

apt students.

You may continue training with an

appropriate instructor adding additional

skills and privileges, as you

desire. The experiences you accumulate

using your sport pilot certificate

can be applied toward other aviation

certificates you may wish to pursue,

such as a private pilot certificate or

an airline transport pilot rating, the

certificate required to fly an airliner.

You may even want to become a

sport pilot instructor and teach others

the skills you’ve acquired.

Medical Fitness

In the United States, once you

earn a pilot certificate, it has no

expiration date. However, for all pilot

certificates other than sport pilot, you

must also possess a valid medical

certificate verifying your medical fitness

to fly. Various classes of “medicals”

exist, depending on the level

of flying you want to do. The most

basic medical, a third-class medical,

requires that a pilot undergo a medical

examination a minimum of once

every two years. If you cannot pass

this medical exam, your pilot certificate

is no longer current.

The sport pilot certificate does not

have this requirement. If you possess

a valid U.S. driver’s license, you may

use this license as evidence of your

medical fitness. However, before every

flight, all pilots are required to selfcertify,

meaning that you don’t fly

when you’re not feeling up to it|that

is, have some malady that’s affecting

you or for which you’re taking medication

that recommends not driving

or operating heavy equipment.

Returning pilots who have allowed

their medical to expire can simply

choose to use their valid driver’s

license as their statement of medical

eligibility if they wish to fly as sport

pilots. However, pilots whose medical

has been denied, revoked, or suspended

must first clear their FAA

record before using their

driver’s license as their

medical.

It’s important to

note that any violation

or health situation

that suspends

your driving privileges

likewise suspends your

flying privileges; in

other words, if your driver’s

license is not currently

valid, you may not use that as

your evidence of medical fitness.

Light-Sport Aircraft-the Machines

In recent years, new aircraft have

become expensive to buy. However,

the establishment of the new LSA

category has dramatically dropped

the price of owning and operating

a new, ready-to-fly aircraft. At the

same time, aircraft designs have

become more modern and efficient.

Prior to SP/LSA, the cost of a new

fixed-wing airplane, for example,

was in excess of $170,000; now,

new fixed-wing LSA are available

from about $40,000 on, with the

average falling in the $60,000 to

$80,000 range.

This cost reduction resulted, primarily,

from a change in the standards

for the construction of readyto-

fly aircraft. With the adoption of

the SP/LSA rule, the FAA accepted

industry-developed consensus standards

in lieu of governmental standards

(known as FAR Part 23), which

added extra cost to the production

of aircraft.

While many pilots may think

about fixed-wing airplanes first,

weight-shift-control aircraft (trikes)

and powered parachutes may be the

most cost effective for sport pilots to

fly, commonly selling for $15,000 to

$50,000. These are simple, open-air

machines that fly between 30 mph

and 80 mph. You take lessons for

12-20 hours and then can carry a

passenger in an aircraft that has met

standards approved by the FAA. If

you’re looking for a different flying

experience, some gliders (sailplanes),

lighter-than-air aircraft (airships and

balloons), and gyrocopters also qualify

as LSA. (See “What Sport Pilots

Can Fly.”)

Other Aircraft Sport Pilots Can Fly

Sport pilots can also build and fly

kit planes. An entire fleet of aircraft

is for sale as “51 percent kits,” meaning

the owner must build more than

half of the aircraft. These aircraft are

called experimental amateur-built

or “homebuilt” aircraft. They must

be checked and given an airworthiness

certificate by an FAA-designated inspector before being flown. If such

an amateur-built aircraft meets the

definition of an LSA, then a sport

pilot may fly it. Many used aircraft

of this type make good purchases,

too, though it’s wise to seek plenty

of expert advice before buying such

an aircraft. Contact EAA’s Aviation

Services staff for advice; call 888/

EAA-INFO or e-mail info@eaa.org.

The SP/LSA rule also established a

new category of experimental lightsport

aircraft or E-LSA. The manufacturer

of these kits may complete

up to nearly 99 percent of the work

of building the aircraft, with the

owner finishing the rest. Before selling

such kits, however, the manufacturer

must first build one aircraft

to completion and show compliance

with the consensus standards governing

the construction of LSA.

Building a kit can be a satisfying

and educational experience, and it

can save an owner thousands of dollars.

Again, EAA has an entire support

network through its Aviation Services

staff to help those who want to build

an LSA airplane kit.

A number of previously manufactured

ready-to-fly airplanes like J-3

Cubs, Aeronca Champs, Luscombes,

and Ercoupes also meet the definition

of LSA and thus can be flown by

sport pilots.

Experimental aircraft kits and

ready-to-fly older aircraft cover a wide

swath of airplane types-from tailwheel

aircraft (taildraggers) to nosewheel

aircraft (tricycle gear) to World

War I and II reproductions to sleek

new all-metal or composite aircraft-

at a wide range of cost, offering sport

pilots even more inexpensive aircraft

choices.

LSA have definitely made owning

an aircraft more affordable.

Financing and insurance are available

for many LSA to allow a broader

range of purchase opportunities for

most budgets.

Fly for Fun!

If you’ve been fascinated with flying

or seek a new adventure, SP/LSA

may be your ticket to a glorious form

of three-dimensional freedom. Never

have we had so many choices of aircraft

for such affordable prices.

Why wait? Visit EAA’s many

resources and see where SP/LSA

could take you. The sky is no longer

limited!

Leave a Reply