NEW COWL – The newer firewall-forward 100-hp Rotax 912S installation comes with a new cowl design created in Germany. The two-piece enclosure can be removed quickly for engine access.

QUICK LAUNCH – Wow! Look at that takeoff angle. You may not make your first launches so aggressively but with practice, look at what’s possible.

TAPERED WINGS – The CH 701’s wings angle down to flat in the center, but this assures the occupants get a good view out to the side. In many designs, the pilot’s head is above the wing’s lower surface.

PLENTY OF POWER – With the 100-hp Rotax 912S engine, Zenith aircraft offers a “rear ring engine mount system for smooth operation.” The installation includes a stainless steel exhaust system, radiator, and 3-blade Warp Drive propeller.

HOME BASE – A new CH 701 sits in front of Zenith Aircraft Company’s 20,000-square-foot production facility in Mexico, Missouri.

JUNKERS FLAPS – While the leading edge slats extend forward of the wing, the CH 701’s Junkers flaps are separate surfaces aft of the wing, maximizing their effectiveness.

HARD WORKING – This “business end” view of the CH 701 reveals a practical design made to function particularly well in some realms of flight. Beefy tires and low-speed wing are parts of this picture.

STANDARD PANEL – This panel is well equipped for most flying you’ll do in the “off-airport” CH 701, though another view shows you can add more avionics if you absolutely must.

FIXED SLATS – Fixed-position slats (“slots” are movable) make for easy pilot workload yet remarkable slow-speed, high angle-of-attack flying.

CURVED LOWER – Tailplanes “lift” downward, but this Chris Heintz design makes that function very obvious with its “upside down wing” horizontal stabilizer. The rudder is a full-flying design.

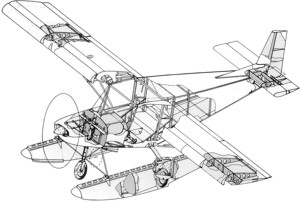

AMPHIB FLOATS – Besides short airstrips, the CH 701 is very good for water operations. Even with the weight of amphibious floats, a 100-hp Rotax 912S-powered CH 701 will leave the water rapidly.

MODERN PANEL – Flat-screen technology is hard to resist, so if you have to have a GPS, EMS, or PFD screen, the CH 701 has space to install it.

Every Light Sport & Ultralight Flying magazine reader has probably heard of off-road vehicles. How about an “off-airport” flying machine? You may not have used the term but you probably know one of the candidates: Zenith Aircraft’s highly functional CH 701.

No one calls the CH 701 the most handsome aircraft in the fleet. That title may be better reserved for sleek carbon fiber jobs. But as a practical aircraft appealing to ultralight enthusiasts, the Chris Heintz design with a 20-year history is head of its class. While the design has not changed much in those two decades, the kit has changed quite a bit to make the builder’s effort easier.

The designs of engineer Chris Heintz have been around a long time, beginning with his early Zipper ultralight-like aircraft. A prolific and versatile creator, his aircraft models have put nearly 3,000 builders in the air. The low-wing CH 601 series is the most popular at better than 60% of all Zenith models followed by more than 700 CH 701’s now flying around the world.

Most of these planes are not in the USA, where about 150 fly. Ultralight enthusiasts who have built kits will find the all-metal CH 701 a reasonable project and quite ultralight-like to fly, though it also has the cabin comforts associated with light sport aircraft.

Off-Airport “Sky Jeep”

The Zenith Aircraft Company, based in Mexico, Missouri, is run by Sebastien Heintz, one of a family of brothers in the aviation business. Mathieu runs AMD, which fully manufactures the CH 601 and other Heintz designs, Michael runs a West Coast dealership selling both kits and fully built Zodiacs (as the line is also known), and Nicholas partners with Sebastien as head of the Zenith’s technical support. A Canada-based business was operated for years by patriarch Chris Heintz, who now lives in the south of France. When the Heintz men get together at airshows they make quite a team.

On at least three occasions, Zenith Aircraft demonstrated at airshows that the assembly of one of their kits could be accomplished in a week – albeit a busy one with long hours – complete with a test flight at the end.

Chris Heintz first introduced his CH 701 in ’86 “as an ‘off-airport’ short takeoff and landing (STOL) kit aircraft.” It was intended to address the desires of sport pilots, yet it had to be a project that first-time builders could successfully undertake.

Zenith Aircraft Company was formed in ’92 to manufacture and market the Chris Heintz designs created by Zenair. Zenith is presently housed in a 20,000- square-foot facility at the Mexico, Missouri airport.

The STOL CH 701 was never meant to be just another pretty light aircraft, according to Chris. Instead it was engineered to bring outstanding STOL performance, all-metal durability, and remarkable ease of construction. These are all qualities that should endear the CH 701 to the ultralight enthusiast looking for an all-metal design with ATV instincts.

Indeed, the STOL CH 701 is a great example of form following function, to borrow an architectural metaphor. Some owners affectionately call their 701 a “Sky Jeep.”

With the STOL CH 701, designer Chris Heintz combined the construction of conventional aircraft with the short-field capabilities of an ultralight aircraft. The CH 701 features fixed leading-edge slats for high lift, full-span flaperons (combined ailerons and flaps), an all-flying rudder, and well-proven all-metal construction.

The Heintz “Sky Jeep” excels in short-field performance. The CH 701 I flew, powered with a 100-hp Rotax 912S engine, was airborne in well under 100 feet of asphalt runway. Rotation came barely after I applied full throttle and lift-off began at 25 mph (as indicated on the ASI). The CH 701 leaped into the sky within 4 seconds from standstill. Naturally, a headwind would further shorten both time and distance for takeoff. In a word: impressive!

Easy Entry

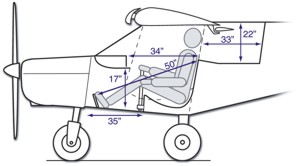

Entry from in front of the wing strut with the gull-wing door opening wide against the bottom of the wing was simple. You merely sit down and swing your legs in, though I helped pull my feet with my hands to clear the front cowl post.

The door closed with a single latch that was easily seen at approximately my outside knee. When opening, a friction latch appeared to prop open the door securely. The CH 701 seats were comfortable and the interior was nicely finished with carpeting.

Shoulder belts are standard on both seats. The CH 701 offered for this flight test was equipped with a good range of instruments that offered all the information needed without technical overload, which seemed appropriate.

I loved the great visibility out of the skylight. These windows are quite useful in turns opposite of the side on which you’re sitting. To your side, you’ll have to look out the side window before turning.

Some folks have been critical of the way the wings “end” or flatten at the canopy, which is located well below the top of the wings. It does look somewhat unorthodox, but one benefit is that your head remains below the wing rather than slightly up inside it. The result is improved lateral visibility. Remember, this design is about function, not stylish beauty. For what it’s worth, Cessna’s new proof of concept LSA has a wing center section that looks very similar, so the Heintz design has good company.

Visibility is not as enormous as the company’s clear-canopy CH 601, but it was more than adequate in the CH 701. Of course, the design provided the downward visibility of all high-wings that many pilots prefer for aerial sightseeing. Flying over the green countryside, I was pleased to have a great viewing platform.

Despite the wide cabin, my headset sometimes bumped a cross member overhead suggesting that the wearing of a helmet is unlikely except for shorter occupants.

The CH 701’s instrument panel switches were easy to reach and instruments could be clearly read. Adequate room was available for a variety of instruments and radios if you simply must load it up with such gear, though doing so starts to violate the simple effectiveness of this design, in my opinion.

Chris Heintz’s Y-shaped joystick handle worked well to my side (in the left seat), but I found it a bit more awkward moving it to the right. With a right-seat occupant, I found motions to that side bumped into the other person’s leg. The left side of the stick was equipped with multiple switches for trim control and radio transmit. The Y-stick should work excellently for training and yields more legroom than dual joysticks.

Powerful hydraulic brakes slowed the 1,100-pound aircraft well and the gear has generous ground clearance for off-field landings. According to others, the CH 701 slab gear is extremely stout. Thankfully, I never tested this ability.

When you open the throttle of a 100-hp Rotax 912S-powered CH 701, be prepared for action. Much like a Quicksilver ultralight, ground break is extremely fast on takeoff. This is a central feature of the design. Its leading edge slots and full-flying flaperons were created to provide fast liftoffs from unimproved airstrips. Believe me, the concept works!

Takeoffs were easy if you were prepared. Landings took a bit more finesse though the airplane can certainly handle rough touchdowns.

I found I needed to keep the stick aft to prevent bobbing. My check pilot said the wing tries to start flying again unless you keep the angle high. Once you’ve started to raise the nose in preparation for final touchdown, keep it up. The wing can fly so slowly at such high angles of attack that lowering the nose just a tiny bit makes the 701 want to resume normal flight.

Approaches were made at 50 mph with a bit of power, though it was obvious that I could come in much slower once I was ready to manage the plane’s special low-speed performance characteristics.

The mechanical flaps were difficult for me to fully deploy. I could get enough flaps down for normal operations, but needed a better technique to get them out all the way. You reach down (where a seat adjustment might be) and must pull forward, an awkward motion that I could only manage to the first notch. Since the company offers electric flaps as an option, I’d recommend them despite a modest weight penalty (see prices).

Fortunately slips were very effective in either direction, thanks to the slab-side finish of the design. Given its slow approach speed potential, I can’t imagine using slips to land very often. Standard large tires can make off-field landings no problem.

Blast Off

The CH 701’s climb angle expressed as deck angle is very steep yet this is not unreasonable as the fixed-slat wing provides genuine STOL characteristics. I measured climb with the Rotax 912S at better than 1,000 fpm dual and nearly 1,500 fpm solo. All measurements were done at about 1,000 msl on a cool 20° F day.

The leading edge slots account for some of the CH 701s capability in fast takeoffs and high rates of climb, but the Hoerner wing tips – angled up to a extended upper surface line rather than rounded tips – help increase effective span by pushing the wake vortices beyond the span.

I cruised at near red line, about 105 mph, thanks to the 100-hp Rotax 912S. Frankly, I found it too much engine for the plane and others have agreed. I’d save the $1,800 extra it costs for a 912S and stick with the highly reliable 80-hp Rotax 912. However, if you want amphibious floats, fly at high elevations, or intend to fill the plane to gross weight on all flights, the 100-hp 912S may be the right selection for you.

Several CH 701 pilots with whom I’ve spoken agreed that the 701 has a rather high sink rate. This is a deliberate design feature that helps you get into tight fields, but I encourage guarding your altitude when not near a landing field, even if a landing field can be mighty small. I was told, “At 1,000 feet agl, you’ll be on the ground in 60 seconds without power.” Later trials showed the 1,000-fpm sink rate to be about right despite the high-lift wing. Wing loading is 9 pounds per square foot, much higher than most ultralights; here’s where such differences show.

In a demonstration of superior low-speed performance, a CH 701 was configured to tow hang gliders in Germany. These aircraft prefer tows below 30 mph and the CH 701 can do it. The low stall speed and excellent climb performance of the aircraft make the STOL CH 701 an ideal towplane for the slow-flying hang gliders.

As is often the case in my line of work, I got to fly a nearly new airplane. As is also often the case, all the pulley wheels and linkages were still a bit tight. Consequently, the CH 701 rudders were rather stiff. They tended to stay where they were put, which gave false impressions of handling. I once thought the plane had a left turn only to realize (from the ball’s position) that I had the rudder slightly depressed from a previous maneuver. Such tightness will loosen in time and should not be an ongoing problem.

Contrasting with the rudders were very responsive ailerons, virtually regardless of speed. When I flew at a low (though probably not minimum) speed, roll pressures seemed almost as light as at cruise speed, though the response degree lessened somewhat due to slower airflows past the surfaces. My Dutch roll coordination exercises were sloppy owing to the stiff rudders. At speed very little rudder is needed while at slow speeds more is needed (logically).

A medium-power stall did break and went rather sharply to the right side, rapidly enough that my check pilot started to reach toward the controls. Despite the abrupt maneuver, recovery was easy. One factor affecting this behavior may have been the powerful engine and a propeller set up for fast climb. Stick with the 80-hp engine and a medium prop and you may never experience a sharper break. Contrarily, low-power stalls never broke and were extremely well behaved.

With stalls coming at nearly 30 mph and with top cruise nearly 100 (in the 100-hp Rotax 912S-powered version), the CH 701 has a wide speed envelope of better than three to one.

Why Cross-Country?

The CH 701 is not your ideal cross-country cruiser. It wasn’t designed for that kind of flying; Zenith’s CH 601 will prove much better in this realm of flight.

But if you fly from unimproved, short, or soft airstrips, the CH 701 may be your dream plane. Like 4×4 off-road vehicles, the CH 701 is not a pretty airplane, but it can take off from airstrips you wouldn’t think of using in your composite LSA. Lots of ultralight pilots can enjoy such gutsy performance.

The CH 701 easily fits Light-Sport Aircraft definitions, though when built as an amateur-built (51%) kit, it retains that airworthiness. Technically it is not an LSA although a Sport Pilot-certificated pilot may fly it under SP/LSA rules. Zenith Aircraft calls the model “Sport Pilot Ready” and that’s an apt description. Chris Heintz with sons Sebastien and Nicholas participated in the ASTM standards-writing efforts. Their aircraft easily meet the standards.

One advantage of building your own kit is that you are allowed to do all the maintenance without asking FAA for permission. You are also permitted to make modifications, something you cannot do with a Special Light-Sport Aircraft (SLSA). In an LSA, additional training is required. On the downside, kit builders remain the “manufacturer” forever, so when you sell your plane (as you will one day), the manufacturer liability sticks with you. For this reason, some kits are simply retired and not sold to customers but that creates a deferred cost. For the CH 701, donations to charitable missions is a great way to offset this problem and aid some good work.

You should be able to get a well-equipped CH 701 in the air for around $35,000 if you don’t put a value on your labor hours. This figure comes from adding the basic CH 701 airframe kit ($12,980) to an 80-hp Rotax 912 engine ($12,800) with a $3,700 firewall forward package plus $1,000 for engine instruments. The parts Zenith supplies total a shade over $30,000. By the time you add exterior and interior finish to your satisfaction and install a few instruments, you could stay under $35,000. In an age of $100,000 LSA, this represents quite a bargain in a long-lasting airplane.

Of course, you may want some accessories like extra wing tanks, doubling your fuel capacity ($995), electric trim ($290), the cabin-widening “bubble” doors ($455), a navigation and strobe light package ($465), cabin heat ($165), or the folding wing kit ($560). Get the larger 100-hp Rotax 912S engine and its install package for $1,800 additional plus the aforementioned options and you’ll go beyond $40,000. While you have a couple of choices in the $50,000 range for a ready-to-fly SLSA, you won’t find any at $40,000 and very few have flight qualities anything like the CH 701.

The longer story of purchase invites you to the Websites at the end of this article where all manner of descriptions and information can be found. You’ll want to talk to Zenith Aircraft. For serious shoppers, Zenith offers an info package for $35 that is as complete as anything I’ve seen from any producer, even those selling $100,000 Special Light-Sport Aircraft.

While no CH 701 will be envied for its striking good looks, the STOL design more than makes up for its workhorse appearance with toughness and outstanding short-field performance. And a 20-year-plus history in the field speaks volumes to the model’s market and aerodynamic success.

I once drove behind a Chrysler Jeep, which had a wide bumper sticker across the top of the rear window that read, “It’s a Jeep thing. You wouldn’t understand.” If you’re an off-airport CH 701 “Sky Jeep” buyer, you probably do understand.

| Seating | 2, side-by-side |

| Empty weight | 580 pounds |

| Gross weight | 1,100 pounds |

| Wingspan | 27 feet |

| Wing area | 122 square feet |

| Wing loading | 9.0 pounds/square foot |

| Useful Load | 520 pounds |

| Length | 20.9 feet |

| Payload (with full fuel) | 400 pounds |

| Cabin Interior | 41 inches at shoulder |

| Height | 8.6 feet |

| Fuel Capacity | 20 gallons |

| Baggage area | 40 pounds, cabin shelf |

| Kit type | Construction kit |

| Build time | 350 to 400 hours |

| Standard engine | Rotax 912 |

| Power | 80 hp at 5,800 rpm |

| Power loading | 13.8 pounds/hp |

| Max Speed | 95 mph |

| Cruise speed | 80 mph |

| Stall Speed | 30 mph |

| Never exceed speed | 110 mph |

| Rate of climb at gross | 1,200 fpm |

| Service Ceiling | 12,000+ |

| Takeoff distance at gross | 90 feet |

| Landing distance at gross | 150 feet |

| Range (powered) | 400 miles – 5 hours |

| Fuel Consumption | about 4.0 gph |

| Standard Features | 80-hp Rotax 912, with electric starter, stainless steel exhaust, radiator, and 3-blade Warp Drive prop; dual 10-gallon fuel wing tanks (20 galoms total); wide, dual doors; independent hydraulic brakes; mechanical flaps; 16-inch tundra tires, removable wings (also see options); complete engine instrument package (Rotax); fully enclosed cabin; in-flight trim; sturdy single piece landing gear construction; steerable nosewheel; all-metal wings, tail, and fuselage; seat belts with shoulder harness. |

| Options | 100-hp Rotax 912S (as tested) and several other engine sizes and brands; additional fuel tanks (40 gallons total); electric trim; folding wings; amphibious or straight floats; cockpit-widening “bubble” doors (add six inches of effective cabin space and more visibility); navigation and strobe lights; cabin heat (with Rotax engine); additional instruments. |

| Construction | All-metal airframe, wing, and tail; many skins predrilled; factory-riveted wing spars and lower cabin frame sides; fiberglass fairing. Kit components made in the USA; sold by U.S.-owned company. |

Design

Cosmetic appearance, structural integrity, achievement of design goals, effectiveness of aerodynamics, ergonomics.

Pros – Short takeoff and landing (STOL) design uses fixed slats to achieve excellent performance. Highly functional aircraft; can operate easily from short, unimproved strips. More than 20 years of field experience with more than 700 CH 701’s flying.

Cons – If you’re looking for sleek or pretty, the CH 701 isn’t your bird. Not fast enough for regular, long cross-country flights. Available only in kit form at present (though cost is therefore lower). Builder remains the “manufacturer” indefinitely.

Systems

Subsystems available to pilot such as: Flaps; Fuel sources; Electric start; In-air restart; Brakes; Engine controls; Navigations; Radio; (items covered may be optional).

Pros – Flaps, trim, electric start, differential brakes are all standard on the CH 701. Fuel (20 gallons standard) contained in the wings, away from occupants. Engine access through easily removed cowling. Generous useful load allows adding optional equipment without losing utility.

Cons – Flap handle proved challenging for me to deploy to the last notch (though this may have been a fact of the new, test aircraft). Trim control located only on left half of stick. Flap position must be checked via lever position or visual; no indicator (though builder could add it if desired).

Cockpit/Cabin

Instrumentation; Ergonomics of controls; Creature comforts; (items covered may be optional).

Pros – With “bubble” doors, the CH 701 is adequately roomy for all but the largest occupants. Baggage space in hat rack position. Very easy entry through wide doors; good for larger or less flexible occupants. Shoulder belts standard. Doors secure well. Reach to panel is good.

Cons – Cabin is modestly wide compared to many LSA (though “bubble” doors add effective width). Center joystick tended to hit right-seat occupant in flight (though I was deflecting more than most normal inputs). Interior is rather Spartan unless builder elaborates.

Ground Handling

Taxi visibility; Steering; Turn radius; Shock absorption; Stance/Stability; Braking.

Pros – Strong, differential brakes aid ground handling. Gear and structure can handle fairly rough terrain. Skylight adds good upward visibility for traffic checking prior to takeoff. Landing gear easily able to handle fairly rough terrain. Good ground clearance.

Cons – Lateral visibility is less open than in the bubble canopy CH 601. Test aircraft had brakes only on the left; going dual will add some cost and weight. No other ground handling negatives.

Takeoff/Landing

Qualities; Efficiency; Ease; Comparative values.

Pros – Takeoff is very rapid and requires a very short distance, perhaps the model’s top attribute; ground roll is only 100 feet and rotation starts almost immediately, thanks partly to leading edge slats. Approach speeds can be very slow with practice, good for the shortest field landings.

Cons – Landings have a slight challenge that demands a little practice; you must keep the nose up once lifted or the CH 701 merely resumes flying. Sink rate after power retarded is quite high (1,000 fpm); this is a useful design feature allowing STOL landings, but you have to anticipate.

Control

Quality and quantity for: Coordination; Authority; Pressures; Response; and Coupling.

Pros – Aileron forces were very pleasant and responsive. Efficient rudder control surface, a full flying design (but see “Cons”). Pitch forces were light without being sensitive, a good combination. Control forces at very low airspeeds permitted by wing/slat design were reasonable.

Cons – Control harmony hard to check in test aircraft as rudders were still tightly adjusted; tended to stick slightly (though possibly only on this aircraft). Wing can fly so slowly that controls necessarily become more sluggish due to low airflow.

Performance

Climb; Glide; Sink; Cruise/stall/max speeds; Endurance; Range; Maneuverability.

Pros – Terrific takeoff performance, better than all but the very lightest ultralights. Climb very strong at 1,000+ fpm at gross. Very capable airplane for low-and-slow flying over landable terrain; extremely slow speeds (in the 30s) with practice and caution.

Cons – Rather high idle thrust sink rate (1,000 fpm); neither glide is very long (though this is considered a deliberate design feature for a STOL airplane). Cruise speed of 80 mph won’t carry you too far. Fuel at 20 gallons standard is four hours or less (though sufficient for most operations).

Stability

Stall recovery and characteristics; Dampening; Spiral stability; Adverse yaw qualities.

Pros – Mild stalls at most angles and speeds (though see “Cons”). Longitudinal and lateral stability appeared very normal in all tests. Response to power input/decrease from trim flight was positive and predictable with few oscillations.

Cons – Stalls with the 100-hp CH 701 (as tested) can be done aggressively enough to cause a sharper break (though recovery remains quick and simple). Adverse yaw was quite significant, something to be remembered at very low speeds the CH 701 can achieve.

Overall

Addresses the questions: “Will a buyer get what he/she expects to buy, and did the designer/builder achieve the chosen goal?”

Pros – Longtime, well-proven supplier (est. 1992) gets excellent comments from customers for technical support and customer service. Can be flown by Sport Pilot certificate holder. Can get airborne with good basic equipment for about $35,000 (and 400 hours of your labor), far less than many light sport aircraft.

Cons – Not a Special- or Experimenta light-sport aircraft (yet), so Amateur-built rules mean builder always remains the “manufacturer,” with attendant legal responsibility. Build time is 350 to 400 hours (though factory support can ease the burden). Even $35,000 is more than some ultralight kits (though with 4-stroke engines, it will be closer).

Leave a Reply