SEAT BACKING – Both seats of the Edge have a solid backrest, unlike most trikes whose forward seat back is not well supported. The backrest folds forward to ease rear entry.

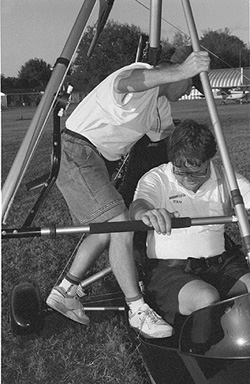

CUSTOMER FIRST – When an instructor takes a student aloft, he helps the student get belted in properly, then performs this maneuver to enter the rear seat.

SUSPENDED GEAR – Unusual on trikes, the deluxe Edge has suspended main gear, using an easily-inspected and familiar bungie system.

BORN TO RIDE – Instructor Rob Hibbard (rear seat) and UF! magazine editor-in-chief Scott Wilcox show the ready-to-learn position.

DEE-LUXE – Typical of the very best in trikes, the AirBorne Edge is a nicely finished, certified ultralight from the Duncan brothers in Australia.

TRIKES STRIKE – Set down, wing into the wind, a trike strikes quite a different pose than a common 3-axis ultralight tied down against the wind. AirBorne builds both the carriage and the wing.

LONG GRIPS – This AirBorne Edge uses a set of well-braced extended handles, allowing a rear-seated instructor to work with a student. They don’t interfere with the front pilot’s movement of the control bar.

INSTRUMENT PANEL – AirBorne dresses up the Edge comparable with the best of the European trikes. Quality craftsmanship is evident throughout. Note the very nice gimbal-suspended compass in recessed area of the panel, and the nosewheel steering bar connected for dual control operation.

AirBorne Windsports is no johnny-come-lately to the ultralight flying scene. The Australian company has been making hang gliders for the international market for years. AirBorne’s owners – Russ and Rick Duncan – once flew for Moyes Delta Pty., another Australian hang glider company (now known for its Moyes-Bailey Dragonfly aerotug), but later branched out on their own.

While both men are thirty-somethings today, they have long experience, starting with competition in hang gliders back when folks still called them “the little Duncan brothers.” They were hot pilots at a young age. Later on, they proved to be solid competitors to the Moyes juggernaut.

Then Came Trikes

A divergence occurred. After linking up with Florida designer Bobby Bailey to produce the 3-axis Dragonfly aerotug, Moyes’s interest in trikes fell by the wayside. They focused on the already popular Dragonfly for their towing promotion.

Meanwhile, the Duncans – now on their own, producing hang gliders – engaged in building trikes. Even this started several years ago, and the Edge model I flew this past spring was a refined entry. Thanks to a hard-working U.S. importer, Scott Johnson of U.S. AirBorne, the Australian manufacturer is beginning to have a bigger U.S. presence.

AirBorne sent a group from Australia for their Sun ‘n Fun ’95 promo effort. They joined up with Johnson, and made quite an impression at the Lakeland, Florida airshow. Aggressively pursuing intro flights with sales prospects, each day brought long hours of ample exposure in their machines. Everyone who noticed had to give the “AirBorne guys” credit for hard work.

I was especially pleased to take my flight with Rob Hibbard. Both Rob and I write monthly columns for the German magazine giant, Fly & Glide (formerly titled Drachenflieger). After years of seeing his name in print, it was a pleasure to meet Hibbard. Flying with him proved equally delightful.

AirBorne remains a dual identity company, still very actively engaged in both hang gliding and triking | different markets all over the globe. But AirBorne’s trike and hang glider production are done at the same place. Russ Duncan handles the trike end of the business, while Rick focuses more on the hang glider end.

Foreign Certification

Attesting to the long time that they have been part of the international ultralight scene, many imported trikes have full airworthiness certificates issued by the government or a government-sanctioned organization. While this is laudatory, it does increase the cost of these machines. And so does the fact that they aren’t kits – they come almost fully-built, with minimal assembly required. However, you get a lot for your money, perhaps the main thing being an awareness that the whole aircraft has been put through a tough testing regimen.

Many pilots believe trikes are unusual aircraft. So do the authorities in the foreign equivalents to our FAA. The officials require the trikes to pass most of the same tests as any 3-axis design, though clearly some procedures had to be changed.

For whatever costs it brings – increased selling price, the feeling of government intervention, longer development times needed to pass a series of tests – certification also brings peace of mind. Rob Hibbard admitted privately that the Edge is overbuilt to assure meeting Civil Aviation Authority standards. Most buyers won’t mind hearing that.

In the last year, the Edge has had a series of improvements to the previous model. The seats were changed to improve comfort. AirBorne has increased the overall height of the seat frame and added an upholstered back support with solid bases and much more padding. Fore and aft adjustment was provided to accommodate pilots of differing heights. Finally, more room was added.

To get the extra room for the seat, AirBorne moved the mast/engine aft of the compression struts. The net effect was a lightening of the nosewheel load, which in turn brought a nice result. The nosewheel comes down slower on landings, generally easing flare timing and making for smoother landings.

AirBorne also added a remote choke, permitting easier starts by allowing you to adjust the choke more precisely. Another change was the move to Rotax’s E-type gearbox and electric starting. “The engine can be started on the gearbox end, which puts far less load on the crankshaft than the earlier system,” says AirBorne.

The Edge uses a suspended gear via bungie cords, which are visible and therefore easily inspected during preflight.

AirBorne believes their machine is Aussie-tough. They advise dealers: “If your customer asks you to prove this, have them stand on the pod or a spat (wheel pant). They won’t break.” Not many airframe producers encourage this form of fiberglass abuse.

Like many trikes, AirBorne’s Edge can perform aerotowing duties for hang gliders, or ultralight sailplanes like the Swift or SuperFloater. The tow point is on the aft side of the propeller, making for an uncomplicated mechanism. As the tow linkage passes through the hollow shaft of the prop hub, the pulling force is exerted in precisely the correct line so as not to disturb flight operations while towing.

The overhead connection to the wing offers two positions to better adjust for a correct CG loading. Flying 2-place, we used the forward position. A heavy-duty strap offers a redundant connection in the unlikely event the mast bolt lets go.

Open but Deluxe “Cabin”

The Edge, like all the world’s best trikes, is relatively open. While some protection is afforded by the nose cone and side fairing, trikes must remain out-in-the-air aircraft, as the control bar movement cannot be restricted by enclosures. Though some creative ideas have been seen in Europe, most trikes closely resemble the Edge in terms of fairings or enclosures. For all regular production trikes, a full-face helmet is advised.

Open-air seating doesn’t mean trikes are simplistic aircraft (although American trike producers have leaned toward more basic machines). For example, the Edge has a dual foot-pedal arrangement, allowing nosewheel steering from either seat.

A hand throttle is mounted where either pilot can reach it on the right seat frame. However, only the front-seat pilot has the foot throttle. The hand throttle overrides the foot throttle, giving a rear-seated instructor control over a student who might back off on the throttle at the wrong time.

Of course, the control bar is shared by each occupant when a student sits up front. Generally on trikes, the rear seat occupant must stretch to reach. However, AirBorne addressed this by fitting the Edge with control bar extenders that give the rear-seat pilot an excellent grip on the bar while the student holds the control bar basetube as though no one else were helping.

The forward seat’s innovative seat back – a big help when flying the machine solo – folds forward to allow entry to the rear seat. Entry is easier than it looks. If an instructor and student are to fly, the instructor generally seats the student up front. After assuring he/she has the seat belt properly fastened, the instructor steps on a side frame member and swings the other leg around the student. While doing so, the instructor can put plenty of weight on the forward support tube, a beefy part that can hold the load without problem.

With instructor backup via his own pedals, a student can quickly figure out the steering scheme. Best taxied from the front, the Edge – like nearly all trikes – relies on a foot throttle. Only the front seat pilot has access to this foot throttle, which makes ground handling easier from up front. (Adjusting power by the hand throttle while taxiing is not workable, as you must use both your hands on the control bar to steady the wing.) While it’s true your hands and feet are all busy, you can taxi a trike in more congested conditions easier than a fixed-wing design.

As Hibbard and I taxied out, we used this capability. Lifting one side of the trike’s wing high, we wove our way out of a gaggle of parked ultralights. In a fixed-wing design, it would have been necessary to stop and move the other ultralights first.

Flight on the Edge

With two aboard, the Rotax 582-powered Edge is a lively machine. Rob demonstrated the first takeoff (always fine by me), and he got on the throttle aggressively. The Edge bolted forward, ran about 150 feet in an accelerating pace, and leaped enthusiastically into the air.

Almost immediately after adding power – via foot throttle, as his hands were occupied with guiding the wing – Rob liberally pushed the control bar forward. This is standard trike procedure, and it works well. A forward support tube prevents pushing out too far, while giving you a fixed reference as to the extent of your control bar movement. Remember, 3-axis pilots: control bar forward is the same as weight back, which equates to stick back.

As if to reassure me about this technique, Rob and I continued outside the pattern with some stalls. The first one was while we still had full power and were still climbing. He slowly eased out the control bar till it touched the forward support tube. Holding it there – the same as full stick aft in a fixed-wing ultralight – the Edge kept right on climbing in a most civil manner.

With several previous trike flights under my belt, I wasn’t surprised by this performance, especially from an ultralight that underwent a thorough Australian government certification program. Nonetheless, it feels good to fly an ultralight with the benign flight characteristics of the AirBorne Edge.

The Edge isn’t particularly fast. I’ve flown some European trikes that have optimized cross-country flying. Some will slip along at speeds faster than 100 mph. At those speeds, the wind feels like a back alley brute beating on you. The Edge was clearly more comfortable.

Though the Edge likes to fly at 50 mph, it’ll go much faster. Vne is over 80. Yet she seems to prefer 50 to 55 mph and is a friendlier machine to fly at these speeds. Of course, trike speeds have little to do with the carriage and almost everything to do with the wing. As in all aviation, the airfoil section is one of the prime determinants of speed range. The Edge wing obviously prefers to optimize mid-range speeds (which agreed perfectly with me).

Climb is listed at 770 fpm, but I’d say this is slightly conservative. Perhaps a function of gaining certification, I found all the AirBorne brochure numbers didn’t overstate performance.

Performance of a machine is not limited to speeds, climb rates and glide angles. Also included are such things as its quietness, a subtle form of performance that makes the machine more enjoyable (tolerable?) for occupants and those below. The Edge was fitted with the latest in noise silencing equipment; the machine was surprisingly well-muffled. Though the Quiet Kit will add $300 to the bottom line, the value is obvious in a short time.

Mystery and Beauty

Weight-shift trike flying is a thing of mystery to most 3-axis pilots, but it becomes a thing of beauty once you learn it. Weight-shift is arguably the most intuitive way to fly. We all think that pulling a stick is logical, but in fact, this is a learned response. Stick back moves the elevator up which causes a tail download which then raises the nose. This is logical? To raise the nose in a trike, you add your weight more aft. I find this more logical.

Coordination in a trike comes when you add push-out to a bank. Of course, this is again the same as back stick in turns. Using something called a J-stroke, you roll into a turn by pulling in a bit (adding speed), then move the control bar left or right, followed by pushing out. The reason why trikes may yet proliferate in the U.S. market is due to an increasing number of training schools where you can go aloft with an instructor and acquire these bar movement skills.

Gaining confidence in the Edge trike comes quickly after a few stability maneuvers. To verify the full-power stall Hibbard had demonstrated earlier, I repeated the control bar movement, but very briskly this time. At cruise speed, I added full power and pushed the bar in one swift movement until it contacted the forward support tube. Even held in this position, the Edge refused to stall, to fall on a wing, or to misbehave in any way. Quite impressive.

Although power-off stalls will break – at least when done quite aggressively – the action is anticlimactic. The natural tendency of the trike suggests that even if you continue to hold the control bar full forward, it will attempt to relieve the stall and resume flying all on its own, and with remarkably little altitude loss.

The throttle responds normally, raising the nose on power up and dropping it gently on power down. Likewise, changing the wing in pitch brings a quick return to level flight after only the briefest period of oscillation. In gentle rolls, the trike is probably more stable than most fixed-wings. However, once rolled to 35° to 45°, the trike becomes moderately spirally unstable like nearly any aircraft.

Break the Piggy Bank

The advantages of a trike enumerate quickly, and these items are true for nearly all brands. After the generic list, you must consider which particular brand creates the package you like best.

Trikes fold up quite small – a leading reason for their huge success in space-tight Europe – and can be carried easily. The wing can go on a simple roof rack, while the trike carriage is carried on a small utility trailer (better than a big box trailer in windy conditions). If you have a pickup truck, it is quite possible to carry the whole package without a trailer. Some trikes actually fold up small enough to fit in the trunk of a larger car.

Trikes handle turbulence well, even if they’re deficient in crosswinds. So as long as you’ve got wind choices, these machines will fly well in more active conditions, theoretically gaining more flying for you.

Trikes can be repaired after mishaps easier than many kit-built ultralights. And they have another attribute: When the manufacturer offers an improved wing, you can easily upgrade. Think of that when your wing sails take their limit in UV degradation. Changing wings is also a way to change the way your machine performs, and you can swap back and forth if you want. All these choices may require you to stay with the same manufacturer, however, to be sure flight characteristics don’t vary.

Now, more specifically, the Edge is a well-equipped model, and indeed, the feature list is impressive. As standard, AirBorne includes the liquid-cooled Rotax 582 engine. The fuel tank is a 12.7-gallon alloy container that should hold up well. Fat, tough tires fitted over 6-inch alloy wheels and wheel pants (or spats in Aussie-speak) come standard, as does the pilot “enclosure.”

U.S. importer Scott Johnson of U.S. AirBorne offers an Edge “fully loaded with aerotow and all options plus shipping [for] about $19,500.” Before you recoil at the size of that number, remember this is for a ready-to-fly, fully outfitted, deluxe aircraft with full Australian CAO 95.32 airworthiness certification. Many European trikes with comparable features will run several thousand dollars more.

Installed into the forward fairing is an instrument panel. AirBorne provides an airspeed indicator, altimeter and hourmeter – normally optional items on most ultralights – which will save you $300 to $500.

On a lower budget, you can select a base-model Edge for about $15,500, plus shipping. Reasonably well-equipped, the basic Edge model is still certified and fully built. Lowering the charge even further is a Rotax 503-powered Edge for just over $14,000, plus shipping.

Among options, the electric start is “already proving very popular,” says AirBorne. This elegant starter system will add about $900 to the tab. Other options include control bar extenders for $215, the Quiet Kit for $305, an aerotug kit for $508, and a wide selection of engine instruments for $525.

Take a Flight on the Edge

No matter your background, trikes as a concept deserve another look from even dyed-in-the-wool 3-axis pilots. They’re fun, solidly built, and very stable flying platforms.

Among trikes, the Edge is a superior ultralight that you should look at closely. My bet is you’ll enjoy an introductory flight with a qualified dealer. You might even want to join the growing ranks of trike pilots with your own “Flight on the Edge.”

| Empty weight | 408 pounds |

| Gross weight | 884 pounds |

| Wingspan | 33 feet 4 inches |

| Load Limit | +6 Gs |

| Fuel Capacity | 12.7 gallons |

| Set-up time | 25 minutes |

| Standard engine | Rotax 582 LC |

| Power | 66 horsepower |

| Power loading | 13.4 pounds/horsepower |

| Max Speed | 82 mph |

| Cruise speed | 63 mph |

| Stall Speed | 34.5 mph |

| Rate of climb at gross | 770 feet/minute |

| Glide Ratio | 11-to-1 |

Design

Cosmetic appearance, structural integrity, achievement of design goals, effectiveness of aerodynamics, ergonomics.

Pros – Fully certified in Australia, a rigorous program. Built and stressed to +6 Gs. Nicely achieved ultralight that looks professional and inspires confidence. Follows well-proven European trike lead in most ways, but shows its own unique qualities. Can carry a large load for its empty weight. Strong and stable flying platform (in spite of what some pilots think). Comes as a fully-built ultralight. Seats two occupants very efficiently. The Edge is built with a distinctive “Aussie touch.”

Cons – Trikes have yet to prove significant market acceptance in the U.S., though this could be changing. Were it not for the acceptance issue, trikes like the Edge could find a strong U.S. market. Close tandem seating won’t appeal to everyone. Aspects of design are not in 3-axis pilot’s “comfort zone,” that is: tailless, weight-shift, flexible-wing design.

Systems

Subsystems available to pilot such as: Flaps; Fuel sources; Electric start; In-air restart; Brakes; Engine controls; Navigations; Radio; (items covered may be optional).

Pros – Among trikes, only a few are more deluxe. First trike I’ve flown with adjustable trim. Good tactile response from trim wheel, which adjusts by increasing or relaxing trailing edge reflex. Beautiful compass installation; best yet? Fitted with electric start and silencers; quite quiet. Brake on nosewheel is above-average effective. Dual throttles work well; friction hand lever overrides spring-loaded foot lever. Excellent repair access of upright engine. Smoothly integrated fuel tank with quantity indicator.

Cons – Nosewheel-only braking might affect steering under some conditions. No other negatives.

Cockpit/Cabin

Instrumentation; Ergonomics of controls; Creature comforts; (items covered may be optional).

Pros – Fiberglass nose cone blends to fabric enclosure with pockets and padding. Seats more comfortable than many trikes; solid front seat backrest is unique and appreciated. Entry is quite unobstructed to both seats. Rear seat control arms make the reach much better than most trikes. Panel easily read (front seat only). Moderate speeds of Edge made cockpit more comfortable than faster trikes. Tying one side of the wing down into a wind works very well to secure whole craft.

Cons – No shoulder belt for forward pilot (though rear belt okay). “Windscreen” only for looks and perhaps a bit of shading for instruments. Raked instrument panel hurts rear-seat readability. No fore/aft seat/pedal adjustment. On the ground, rear-seat occupant’s helmet may touch vibrating mast; not a problem in air. Very limited baggage area if both seats occupied.

Ground Handling

Taxi visibility; Steering; Turn radius; Shock absorption; Stance/Stability; Braking.

Pros – Wide tires all around give a well-supported feel and offer extra suspension. Bungie suspended main gear softens bumps. Each seat has full nosewheel steerability. Excellent visibility, even without moving a wing out of your way. Tight turning radius possible. Taxiing shows trike flexibility via wing movement. Though I don’t care for wrong-way steering, the Edge nosewheel wasn’t skittish like some lightweight trikes.

Cons – Wrong-way steering is | well, a trip! It’s not quite as weird as it seems, but it’s close. It may be all that’s wrong with trike ground handling, though not needed much on takeoff. If taxiing in strong crosswind, muscular strength required to hold wing steady.

Takeoff/Landing

Qualities; Efficiency; Ease; Comparative values.

Pros – Trike takeoffs look weird, but aren’t at all. You have to experience it to believe it. Touchdown is very controllable, thanks to responsive pitch control (without being touchy). Visibility is huge on landing. Bungie suspension and beefy tires offer a uniformly smoother touchdown. Energy retention in ground effect is quite strong.

Cons – Takeoff visibility lacks a bit directly in front of you (due to pod and high carriage angle). Fast touchdowns demand steadiness of nosewheel movements. Crosswind capability is weak if you can’t land on a runway angle. No ability to slip. Takeoff roll on heavier Edge longer than expected.

Control

Quality and quantity for: Coordination; Authority; Pressures; Response; and Coupling.

Pros – Don’t let that “reversed control” thing bother you; it’s easily learned and more intuitive than you think. No adverse yaw (no ailerons to induce it). Harmony comes rather naturally to trike controlling; you move yourself back in a turn and turn coordinates. Using this control, steep turns are beautiful. Roll rate is adequately brisk.

Cons – In spite of the easy-to-learn control bar movement, the “reversed control” prevents some pilots from accepting trikes. Precision turns to headings better than some trikes, but still less precise than 3-axis aircraft. Crosswind capability is lacking. Roll control pressures are on the high side.

Performance

Climb; Glide; Sink; Cruise/stall/max speeds; Endurance; Range; Maneuverability.

Pros – Good performance in several parameters: climb is strong, glide is stronger than average ultralights (11-to-1 factory says), low-rpm efficiency is quite good. Flight at reduced power is surprisingly quiet. Slow flight is an easy regime in which to operate the Edge, which makes it enjoyable in close-to-the-ground flight.

Cons – The Edge isn’t as fast as some trike designs (which didn’t bother me, but which may be a negative for others). Takeoff roll is on the long side.

Stability

Stall recovery and characteristics; Dampening; Spiral stability; Adverse yaw qualities.

Pros – Stability – where some think trikes look deficient – is actually a strong suit. Australian certification assures you the Edge has met tough standards. Pitch and roll stability are excellent. Throttle response produces the desired effect, as does the pull/push-and-release exercise. Stalls were nonevents. Power-off stalls broke, but very mildly; power-on stalls didn’t. No adverse yaw present.

Cons – No negatives discovered.

Overall

Addresses the questions: “Will a buyer get what he/she expects to buy, and did the designer/builder achieve the chosen goal?”

Pros – AirBorne’s Edge is an excellent example of the state-of-the-art in trikes. Possessing Australian certification will reassure many buyers. Nicely achieved construction; quality hardware throughout. The trim device works and is appreciated. The rule with trikes is you must fly one to understand their ease of operation. If you take a couple hours flight instruction, you’ll quickly learn to master the machine. Stable flying platform offering excellent visibility. Easy to ground handle and park.

Cons – rikes still haven’t won a large American following; this may only affect you if you want to sell one. Controls are unorthodox to 3-axis pilots, and they require more muscle than most pilots expect. Prices seem steep (unless you recall they’re fully-built and have certification).

Leave a Reply