ZIPPERED ENCLOSURE – CGS Aviation’s Hawk provides a full enclosure and once set a precedent for this configuration among ultralights that were all open-cockpit designs in ultralighting’s formative era. The Hawk method still works well

SMOOTH RUNNING – Though Rotax dominates the market with sales and service, Hirth remains the smoothest running engine brand many pilots will experience in ultralight aircraft.

SECURE SEATING – Though simple and light in their construction, Hawk seats have adequate padding and support while holding occupants securely in place with 4-point harnesses.

FULL PANEL – The CGS Hawk, in either single- or 2-place configuration, can accommodate a large number of instruments in its generous panel. Here we see full engine and flight gauges with plenty of room left over for radios or GPS units.

BIG MAN – Chuck once bragged that he was one of ultralight aviation’s biggest manufacturers and he meant it two ways: CGS Aviation built a lot of Hawk ultralights and Chuck seems to enjoy more restaurants than some other designers.

NOSE JOB – Peering inside the nose of the Hawk reveals its fully steerable nosewheel (located aft of the pedals) and mechanical brakes. Carpeting this area quiets the machine and covers the structure, which has been shown to protect occupants during poor landings.

Chuck’s Patented Reduction Drive?

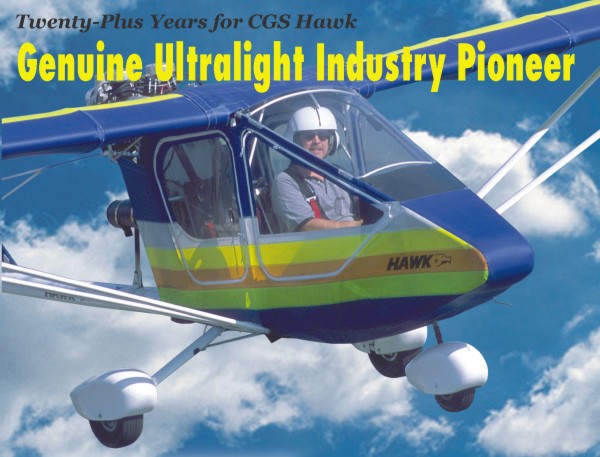

The nation is focused on the celebration of 100 years of powered flight, thanks to efforts by a couple of Ohio brothers in 1903. But ultralight aviation has its own bigger-than-life hero from yesteryear and he’s also from Ohio.

Chuck Slusarczyk needs no introduction because almost everyone involved with ultralight aviation for any length of time knows the jolly designer of the Hawk series of ultralights.

Chuck first flew gliders just as did Orville and Wilbur Wright. Like the famous Wrights, he ignored those who said he couldn’t do what he hoped to do – in Chuck’s case, bring to market an ultralight that broke new ground in several important ways. For one, you had no chance to foot-launch it.For those who became ultralight enthusiasts more recently, the rule in the early 1980s – before passage of FAR Part 103 – was that ultralights had to be foot-launchable. When Slusarczyk first introduced the Hawk, a demonstration of foot-launching was required; since the Hawk was fully enclosed, the pilot could not provide the demonstration, if asked.

Despite naysayers, the man with the hard-to-spell last name did exactly what he said he would and, in doing so, helped spark an entire generation of ultralight design. The 1,500 Hawks flying today are proof positive that he gambled correctly.

Going W-A-Y Back

For an entire decade before powered ultralight aircraft arrived on the aviation scene, Chuck designed and built hang gliders. This is how I came to know the big man from Ohio. Long before I went aloft in my first powered ultralight, I flew hang gliders and my path often crossed Chuck’s.

The old Chuck’s Glider Supplies – which was later renamed CGS Aviation – manufactured hang gliders named the Swooper, the Spitfire, and the Falcon. The latter was his big success in that market segment; Falcons evolved through seven iterations. Chuck’s Glider Supplies became one of the largest manufacturers in the East at a time when all the big manufacturers seemed to be located in California.

Like many of his fellow hang glider designers, Chuck started experimenting with engines back in the 1970s, before we called these contraptions “ultralights.” After experimenting with delta-wing hang gliders, he began using the biwing Easy Riser as the airframe for his little powerplants. In those early days, 10 horsepower had to suffice in order to keep weight down.

A need for increasing power came when these little flying machines started to develop into ultralight aircraft. Long before Rotax was known in aviation and even before its predecessor, the Cuyuna, engines had not become a separate industry. You bought and tried engines and had to figure the fitting, muffling, and cooling. Engines had to be light because the airplanes were light – still foot-launchable, for some years yet – so the choices were few.

A key way Chuck helped that early ultralight industry was to be among the first to sell “power kits” so that enthusiasts could build their own self-launched hang glider. But Chuck did much more than sell power kits and parts. He also helped the industry by being a trailblazer.

Baby Hawks

While he was still known for his powered Easy Riser, Chuck took out a stack of clean sheets of drafting paper and began to create a legend. He called the resulting ultralight the Hawk. It set a pace with several firsts.

The Hawk was the first ultralight to incorporate conventional 3-axis controls even including a steerable nosewheel or tailwheel. You may see these design features as common, and today they are. But ultralights were born of powered hang gliders and the early control systems were nothing less than amazing in their diversity. Many weren’t particularly effective. Having worked in the conventional aviation industry earlier in life, Chuck knew standard systems and he saw an advantage in providing them. The company’s steady sales over two decades are a testament to the accuracy of his vision.

Those early Hawks were also the first ultralights to use fully functional wing flaps and full strut bracing. Again, standard stuff, you may think. But flaps were very uncommon then and someone had to break new ground. Most ultralights still used wire bracing. Chuck perceived that conventional FAA pilots wanted aircraft that were, well, conventional.

But what really set the ultralight community on fire was the Hawk’s fully enclosed cabin. Ho-hum, you say. Common, you say. Yes, today that’s true. But in those days of mandatory foot-launch, Chuck went far out on a limb by enclosing his cabin. The Hawk didn’t even have a pretense of foot-launch capability; it simply wouldn’t let you put your legs down on the ground. Of course, the rule had become a sham because aircraft had gained landing gear and had gotten heavier. Some factory he-men could stagger into the air, given a strong headwind, but this was an athletic feat, not a piloting skill.

Chuck made his stand on “no foot-launching” in early 1982. He gambled well, as indeed, FAA introduced the innovative Part 103 ultralight rule by September of that year. It had no requirement for foot-launching, nor any restriction against full enclosure. Hence, the Hawk overtook many other designs. Chuck never looked back.

Today’s Hawk is changed only by virtue of model proliferation involving a series of refinements. The lineup of 2003 includes three single-seat models – the Classic, Arrow, and Plus – and two 2-seat models – the II Classic and II Arrow. I’ve flown every one of these variations. Every chance I get to fly a Hawk is an anticipated experience and one I’ll never turn down. Let’s get into one of the latest variations (the Hawk II Arrow) and familiarize ourselves with it.

Feature-Laden Hawks

Chuck is a big fellow. So are many of his customers. I suppose some figure that if a large guy like Chuck designed the ultralight for someone of his dimensions, a lot of other healthy American pilots will also fit. They’d be right. The Hawk is a wide, roomy aircraft.

Entering through the zippered doors is simple. The large zippers work well and you peel the door open to its front “hinges.” Getting in is then merely a matter of sitting down and swinging your legs in, which you can do easily as the door opening extends well forward. When you close the doors, you can leave the zippers strategically open to bring in fresh air on hot days.

Our test Hawk II Arrow differs from the lower-priced and lighter Hawk II Classic due to the use of a few curved fuselage members. A close look at the exterior photos reveals the gently curved parts. Overhead, the shaped member allowed me to wear my helmet without banging my head. I may be a disappearing breed of ultralight pilot who prefers a helmet inside a fully enclosed aircraft but helmets offer serious, proven protection in mishaps and I appreciate the Hawk II Arrow for letting me wear my helmet comfortably.

Flaps appear immediately to your left approximately by your ear. The flap lever has clear detents; the system is simple but has proven itself on my previous Hawk flights. Of course, simplicity has long been a useful design premise and this lesson isn’t lost on Chuck. Flaps can set for three positions of 15, 20, and 30°. CGS Aviation once experimented with a reflex position but gave it up as ineffective. Flap lever detents are clear enough that you can guide the lever to the next setting without looking.

Starting with the side tube-mounted throttle, I found a generally comfortable reach to both stick and rudder pedals for someone my size.

Start Your Engine

As he so often has done, Chuck oversaw installation of a Hirth engine to this test Hawk. This time it was the 80-horse, 2-stroke, 4-cylinder Hirth F-30 and as always, the Hirth showed me two wonderful qualities. First, it started without a protest. Secondly, it ran so smoothly, any Rotax seems rough in comparison.

Hirth has its detractors, too, and I know some would argue with my easy-starting assessment. But I’ve never heard anyone deny the German brand runs very smoothly. Since it packs a punch with power as well, the 4-cylinder F-30 will attract its share of pilots. Additionally, the test engine this month now has 100 hours on it, Slusarczyk says, and no hiccups. Chuck reasons that it must only produce 20 hp per cylinder while a Rotax 582 produces 32.5 hp per cylinder. This may equate to longer life for the Hirth.

The big 4-cylinder engine was specifically chosen to see if this Hawk could do duty as a glider tug. Factory (and airline) pilot Grant Smith has sustained 35 mph in the rig, a reasonable speed for towing hang gliders. Chuck told me that using the larger wing in their design catalog – a 34-foot span version on many older Hawks – the tug could get even closer to hang gliding tow speeds. Plus, you can cruise at 75 to 80 mph, an advantage for tug ferrying. The Bailey-Moyes Dragonfly is an excellent tug but cruises too slowly if a lot of ferry flying is involved.

As I prepared for flight by starting my taxi, I recalled the nosewheel has a wide rotation range. As long as you maintained a little inertia you can spin around quickly to check for traffic before takeoff. Yet this doesn’ttranslate to a particularly tight turning radius at slow maneuvering speeds. For the tightest turns, you’ll need differential brakes. The nosewheel is mounted well aft of the nose, barely a foot in front of the joystick base.

My only concern with the nosewheel was a lot of clunking as we hit irregularities in the turf taxiway. Noise usually relates to wear in my experience, so owners will want to keep an eye on nosewheel parts.

I first flew a Hawk in 1983 and 20 years later, I still find the design to be one of the most delightful airplanes in ultralight aviation. The Hawk offers such complementary behavior during takeoff and landing that I recommend it enthusiastically to beginners, though even old veterans like myself can appreciate an airplane that is easy to launch and land.

Usually I wait with landing evaluations until later in my time with the ultralight, hoping to better discover how a plane responds. The Hawk’s landings are so straightforward - and so much fun – that I immediately went around the pattern for a few touch and goes.

Full-flap landings were especially modest in touchdown. I used Chuck’s “50-is-nifty” approach speed. This gave a wide margin and later I achieved approaches that were significantly slower. Without flaps I had consistently firmer landings so the use of them seems advised.

The Hawk uses its flaps productively. Side slips worked fairly well, but I ran out of arm to push the stick forward enough. Given the potent Hawk flap system, you won’t need to employ slips very much. If you prefer slips, keep your flap settings low and watch your flare timing.

True Ultralight Flight

The Hawk is very pleasant above the countryside. You can choose 1,500 feet or 50 feet of altitude (if safe) and I think most pilots will be very comfortable with their control of the Hawk. It is highly predictable and experiences no control slop.

Nonetheless, no one would say the Hawk has a fast roll rate. Her controls do what you want when you want it for the majority of flying. Do you need more? Roll response is very good, though, what pilots come to expect from the well-packaged Hawk abilities.

A rare handling complaint comes during vigorous hard rudder applications; to come in with enough aileron, the stick bumped into my leg and ran out of range.

The Hawk’s pitch response was excellent, holding attitude differences without the need for trim. She’s clearly a dynamically well-balanced aircraft. Despite this ease, trim is useful in changing conditions. As with its other systems, the Hawk offers trim that works well.

Never did I feel at a loss of control, even landing in crosswinds. Rolling into turns requires low physical effort and modest stick movement while break-out force, or roll response out of turns, was more authoritative than many ultralights.

Full throttle in the powerful 80-hp Hirth powerplant brought 72 mph indicated (though I was not able to verify airspeed indicator (ASI) accuracy). Even backed off on the throttle and with stick well forward, the Hawk didn’t want to exceed about 80 mph indicated. I wasn’t real aggressive but believe I was close to what felt like a maximum speed of the bird. I’d call this a great safety quality. To get that much forward stick, I had nearly run out of arm movement.

Another way to talk about overall Hawk performance is to examine the results of the 2001 Second World Air Games and Microlight Championships in Spain. Two Hawks finished first and second in the single-seat fixed-wing microlight class. Any designer would be proud of such a performance in an aircraft that was 20 years old last year.

Stall occurred at about 38 mph indicated, but factory folks had said something about a pitot tube getting bent, so perhaps the ASI was not 100% accurate. Stall at 38 mph seems faster than it felt for this aircraft. Before I flew, Chuck said the stall was a little sharp although my several experiences didn’t find any hard break. During full-power stalls, the aircraft just hung on the prop at 42 mph indicated.

The Hawk’s adverse yaw was pretty significant and didn’t want to dissipate quickly. A distinct prop burbling could be heard during all asymmetric conditions so rather like those noisy ribs on the side of a freeway, you are given an audible warning that you aren’t flying straight.

Your Own Hawk Wings

CGS Aviation is rare among modern ultralight builders by offering more single-place versions than 2-seaters, in a 3-to-2 ratio. Sales results prove this is the right selection. More than 1,100 Hawk single-seaters have sold compared to around 450 of the 2-

seat models. I regularly have arguments with “experts” who insist only 2-place ultralights will sell. Maybe some companies can’t sell a single-place model, but CGS Aviation sure can.

In the single-place lineup today are the Hawk Classic, Hawk Arrow, and Hawk Plus. CGS can also supply an agricultural spraying version of the Plus. Two-seaters are called the Hawk II Classic and Hawk II Arrow.

The Hawk Classic is the older, simpler model. When you move up to the Arrow model you get the fuselage featuring the curved windscreen (rather than the Classic’s flat windscreen) plus streamlined struts. The Arrow has a larger vertical stabilizer and rudder plus a strengthened boom tube. On any Hawk model you can choose between taildragger and tricycle gear. All the Hawk single-seaters are priced with the Rotax 447 engine that has proven sufficient for most operators. The 2-seaters work fine with a dual carb 50-hp Rotax 503 though pilots generally install even larger engines.

The single-seat Hawk Arrow taildragger is my favorite, but it comes with requirements attached. Because it is 28 pounds heavier (282 pounds empty) than the 254-pound Part 103 weight limit, it must be N-numbered and you must have a pilot’s certificate. Despite liking the creature comforts of the curvier Arrow, I admire the simpler Classic. Lighter ultralights tend to have better handling and agility than heavier ones.

The single-seat Hawk Classic uses a simpler structure with squared lines. This helps it stay light and within Part 103’s tight 254-pound limit (if carefully built). Yet big pilots or those who prefer to wear a helmet (like me) may prefer the roomier Arrow with its curved fuselage structural members. The curved tubes help form the windscreen’s shape, which gets rid of a significant glare in the Classic Hawks. Fly with the sun at your tail and the Classic’s flat windscreen is clear and the view wonderfully large. But turn into the sun and forward visibility becomes restricted at the wrong angles. The Arrow’s curved upper cockpit member puts a convex shape in the windscreen and the result is better in bright sun from any angle. The subtle shape difference is popular; around 200 Hawk Arrows are flying today.

Hawk 2-seaters are tandem and I’d rather be in the front seat. But the rear has decent visibility for occasional passengers. When you need to pack some camping gear or luggage, the II Classic and II Arrow offer significant space. You pay about $3,000 more for the extra hardware and larger Rotax 503 engine of the 2-seat models.

Positioned somewhat in between is the Plus model, which is basically a 2-seater without the second seat. This configuration is 50 pounds lighter than even the trim II Classic, the factory says; yet it offers more space for those who want to carry items with them. Its price is mid-way between the other singles and 2-seat Hawks. The Plus model cannot qualify for Part 103 due to its higher empty weight (350 pounds empty).

Fair prices and a trustworthy, reliable design add to CGS Aviation’s engaging and entertaining owner, Chuck Slusarczyk, in making the Hawk an icon of the ultralight industry. Some 1,500 units prove the Hawk is one of the success stories in all of light aviation.

| Seating | 2, tandem |

| Empty weight | 420 pounds |

| Gross weight | 950 pounds |

| Wingspan | 31 feet 6 inches |

| Wing area | 159 square feet |

| Wing loading | 6.0 pounds per square foot |

| Length | 22 feet 2 inches |

| Height | 4 feet 8 inches |

| Kit type | Assembly kit |

| Build time | 100-200 hours |

| Standard engine | Rotax 503 DC 1 |

| Power | 50 hp |

| Power loading | 19.0 pounds per hp |

| Cruise speed | 55-75 mph |

| Never exceed speed | 100 mph |

| Rate of climb at gross | 700 fpm |

| Takeoff distance at gross | 220 feet |

| Landing distance at gross | 200 feet |

| Notes: | 1 Engine on this test Hawk II Arrow was the 80-hp Hirth F-30; power loading 11.9 pounds per hp. |

| Standard Features | Tandem 2-seater, dual controls, flaps, tri-gear/taildragger (steerable nosewheel/tailwheel), semisymmetrical airfoil, lower rib battens, fiberglass gear legs, 16-inch wheels, curved overhead/windshield, full enclosure, doors, 4-point shoulder harnesses, streamlined struts, 10-gallon tank, 2-blade wood prop. |

| Options | 55-hp Hirth 2703, 65-hp Hirth 2706, 80-hp Hirth F-30, 65-hp Rotax 582, 60-hp HKS 700E, electric start, folding wings/tail, mechanical/hydraulic brakes, fiberglass nose cone, dope and fabric covering, trim tabs, 10-gallon wing tanks, wheel pants, ballistic chute, instruments, floats, 2- or 3-blade composite prop; quick-build kit, fully-assembled option. |

| Construction | Aluminum airframe, steel components, fiberglass gear legs, Dacron wing, tail, and control surface coverings. Made in the USA; distributed by a U.S.-owned company. |

Design

Cosmetic appearance, structural integrity, achievement of design goals, effectiveness of aerodynamics, ergonomics.

Pros – Wisely unchanged for 20-plus years, the Hawk remains a great choice among all ultralights. Behaves exceedingly well, applicable for both beginner and veterans. Many satisfied customers. Good safety record with a fleet of 1,500 Hawks. Company owner Chuck Slusarczyk is one of the most memorable characters in ultralight aviation.

Cons – Design is not the latest-and-greatest though Hawk lacks for nothing except perhaps new styling. Tandem seating may be optimal for aerodynamic reasons but you can’t see your passenger. All-aluminum structure carries somewhat more build complexity than welded steel fuselages.

Systems

Subsystems available to pilot such as: Flaps; Fuel sources; Electric start; In-air restart; Brakes; Engine controls; Navigations; Radio; (items covered may be optional).

Pros – Reasonably effective brakes operated by lever on joystick. Electric starting eases effort with this 80-horse Hirth engine. Flaps are standard, work very well, and are easily operated. Flap position easily identified. Panel could accommodate more instruments, GPS, and/or radio.

Cons – Nondifferential brakes did not aid with steering. No trim installed (though hardly needed if one pilot operates aircraft). In-cabin pull starter on a smaller engine will be challenging due to the layout. Refueling causes some fumes inside cabin.

Cockpit/Cabin

Instrumentation; Ergonomics of controls; Creature comforts; (items covered may be optional).

Pros – Spacious cabin is larger than other tandem, enclosed ultralights. Entry is simple; bottom first (lowering nosewheel), then swing legs in. Seating quite comfortable. Reach to controls very convenient. Some area available for cargo if weight and balance verified.

Cons – Sits on tail when unoccupied, frowned upon by some potential buyers. Zippered doors seem too basic for those used to general aviation aircraft (though can be folded inward a bit to allow ventilation). No quick seat adjustment. Tandem seating is not universally preferred.

Ground Handling

Taxi visibility; Steering; Turn radius; Shock absorption; Stance/Stability; Braking.

Pros – Taxi visibility is good, even to the sides as you sit at leading edge of wing. Good clearance on rougher fields, thanks to tall gear position. Steering was quite responsive, pivoting with ease. Wide stance offered good stability. Good gear absorption.

Cons – Though steering is responsive, turn radius is not particularly tight and without differential braking, planning will be required on a crowded ramp. Visibility from rear seat is much diminished (especially without a skylight).

Takeoff/Landing

Qualities; Efficiency; Ease; Comparative values.

Pros – One of the best ultralight aircraft for takeoffs and landings. Excellent approach to landing visibility. Recommended 50-mph approach has a liberal safety margin. Little precision demanded to achieve smooth touchdowns. Good energy retention in ground effect. Flaps were very helpful on approach. Good controls for crosswind operations.

Cons – Slips will run out of forward stick if flaps are fully deployed; use one or the other (flaps work so well, no slip is needed). My landings without flaps were consistently firmer, suggesting you should use them on all landings. No other negatives.

Control

Quality and quantity for: Coordination; Authority; Pressures; Response; and Coupling.

Pros – Excellent overall control feel and response; not too light or quick yet you get what you expect easily and authoritatively. Steep turns were comfortable and efficient. Control harmony is very good. Pitch response will be comfortable to pilots of all experience levels.

Cons – Roll rate isn’t fast and runs out of range in some conditions (though these are outside most normal use). Adverse yaw was quite significant; coordinated control usage recommended at all times. No other negatives.

Performance

Climb; Glide; Sink; Cruise/stall/max speeds; Endurance; Range; Maneuverability.

Pros – Hirth remains one of the smoothest engines in ultralight aircraft. The Hawk flew efficiently, holding altitude even at power settings down into the low 4,000-rpm range. Performed very well in low-and-slow flying, which I consider to be the ultralight realm. Factory literature speed figures proved accurate.

Cons – Not a particularly “fast” ultralight. Climb and sink rates seemed only average, not exceptional. Though good overall, performance doesn’t stand out in any category.

Stability

Stall recovery and characteristics; Dampening; Spiral stability; Adverse yaw qualities.

Pros – Mild, easily recovered stalls for all types attempted, even when aggravated. Power-on stalls never broke. Stall speeds down into the 30s. No spiral instability noted during any maneuver attempted. Cockpit cage has proven its ability to prevent some injuries.

Cons – Adverse yaw requires coordinated use of controls (as on many other aircraft designs). Deep slips with full flaps will run out of control range; I recommend using only the flaps, which are quite efficient.

Overall

Addresses the questions: “Will a buyer get what he/she expects to buy, and did the designer/builder achieve the chosen goal?”

Pros – Excellent choice for a recreational aircraft. Priced reasonably. The Hawk, and its popular designer, are icons of ultralight aviation; when you sell, recognition won’t be a problem. For overall flight and handling qualities, all the Hawks are among my top recommendations.

Cons – Design has changed little over the years, reducing its appeal to those who want the newest creations. A few ultralight designs might have even lower prices. Folding wing is optional.

Leave a Reply